Coating Thermal Noise & Thin Films

Measure and reduce coating thermal noise — the dominant sensitivity limit in LIGO's most critical frequency band — through material characterization, computational optimization, and novel coating architectures including crystalline AlGaAs.

Research area

The mirrors in LIGO are among the most precisely controlled objects on Earth — seismically isolated, suspended as pendulums, and cooled by radiation to suppress every conceivable source of mechanical noise. Yet the dominant noise source in the most sensitive frequency band (50–300 Hz) is a few micrometers of dielectric coating on each mirror surface. These thin films — alternating layers of tantala (Ta₂O₅) and silica (SiO₂) deposited by ion-beam sputtering — are essential for achieving >99.999% reflectivity, but their internal mechanical losses couple to the thermal bath and produce Brownian displacement noise that sets the floor of the detector.

Contents:

- A brief history

- The physics of coating thermal noise

- Measuring mechanical loss

- Material systems

- AlGaAs crystalline coatings

- Computational coating design

- Deposition, annealing, and scatter

- Coatings for LIGO Voyager

- Competing approaches

- Connections to other fields

- Our contributions

- Key references

A brief history

Coating thermal noise was not always recognized as a dominant noise source. The conceptual foundations were laid by Callen and Welton (1951), who formulated the fluctuation-dissipation theorem (FDT) relating mechanical dissipation to thermal fluctuations. For decades, however, attention focused on pendulum thermal noise and seismic isolation — the coatings were considered too thin to matter.

The modern understanding began with Peter Saulson (1990), who applied the FDT rigorously to mirror suspensions and showed how internal friction in mechanical systems produces position noise. Yuri Levin (1998) introduced the “direct approach” to computing thermal noise — applying a virtual oscillating pressure to the mirror surface and computing the resulting dissipated power — which made it straightforward to calculate the coating contribution. Levin’s insight was that thermal noise from a small, lossy region could dominate over noise from a large, low-loss region if the strain energy density was high enough.

Gregg Harry and collaborators at MIT/LIGO (2002) provided the critical experimental confirmation: direct measurements of coating mechanical loss in tantala/silica stacks showed loss angles orders of magnitude above the substrate, establishing coating Brownian noise as the dominant noise source in the LIGO band. Steve Penn (2003) developed the theoretical framework connecting individual layer loss angles to the total coating thermal noise, distinguishing bulk and shear contributions. Gabriela González contributed foundational work on thermal noise in interferometer suspensions that informed the broader understanding of dissipation-fluctuation relationships in precision measurements.

At Caltech, Hank Raab played a key organizational role in the LIGO coating research program, coordinating the effort across multiple institutions. Aaron Gillespie (Caltech PhD, 1995) made early measurements of thermal noise in mirror suspensions. Kenji Numata (2004) developed broadband techniques for measuring coating thermal noise in rigid Fabry–Pérot cavities that became the basis for subsequent tabletop experiments — including those built in our group.

The physics of coating thermal noise

The fluctuation-dissipation theorem connects mechanical dissipation to the spectral density of thermal displacement noise. Levin’s direct approach applies a notional oscillating force $F_0 \cos(2\pi f t)$ with the spatial profile of the laser beam to the mirror surface, computes the time-averaged elastic energy $U$ stored in the coating, and reads off the power spectral density of displacement noise:

\[S_x(f) = \frac{2 k_B T}{\pi^2 f^2} \frac{W_\text{diss}}{F_0^2}\]where $W_\text{diss} = 2\pi f \, U \, \phi_c$ is the power dissipated in the coating and $\phi_c$ is the effective coating loss angle. The $1/f^2$ dependence means coating thermal noise is worst at low frequencies — exactly where gravitational-wave signals from massive binary systems are strongest.

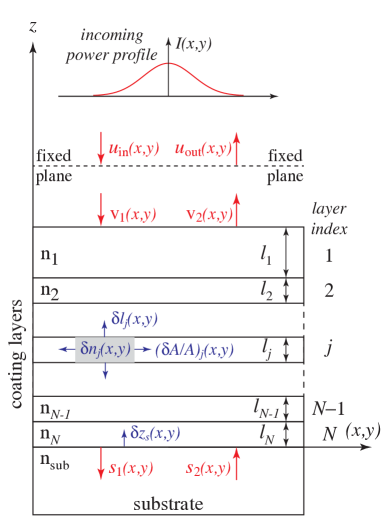

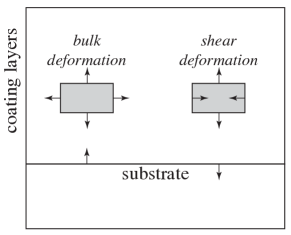

The effective coating loss angle $\phi_c$ is not simply the loss angle of any single layer. It depends on the elastic properties and thicknesses of every layer, the Poisson ratios of the coating and substrate materials, and the way strain energy is distributed through the stack. Hong et al. (2013) developed a complete treatment that separates bulk and shear loss contributions and accounts for photoelastic corrections:

\[\phi_c = \sum_j \frac{d_j}{d} \left( q_j^B \, \phi_j^B + q_j^S \, \phi_j^S \right)\]where $d_j/d$ is the fractional thickness of layer $j$, $\phi_j^B$ and $\phi_j^S$ are its bulk and shear loss angles, and $q_j^B$, $q_j^S$ are weighting factors that depend on elastic moduli and Poisson ratios. This decomposition is essential for understanding which layers contribute most to the total noise and for optimizing the coating design.

Why coatings dominate: a scaling argument

The coating is ~4.7 µm thick on a substrate that is 200 mm in diameter and 200 mm thick — the coating is less than 0.01% of the mirror volume. Yet it dominates the thermal noise because the strain energy density under the laser beam is concentrated in the surface layers. For a Gaussian beam of radius $w$ pressing on a half-space, the strain energy in a surface layer of thickness $d$ scales as $U_\text{coat} \sim F_0^2 d / (Y_c w^2)$, while the substrate contribution scales as $U_\text{sub} \sim F_0^2 / (Y_s w)$. The ratio is:

\[\frac{U_\text{coat}}{U_\text{sub}} \sim \frac{Y_s \, d}{Y_c \, w}\]For LIGO parameters ($d \approx 5\;\mu$m, $w \approx 6$ cm, $Y_c \approx Y_s$), the coating carries only ~10⁻⁴ of the total strain energy. But the coating loss angle ($\phi_c \sim 4 \times 10^{-4}$) is roughly 4,000× higher than the fused-silica substrate ($\phi_s \sim 10^{-7}$). The product $U \cdot \phi$ — which is what enters the noise formula — makes the coating’s noise contribution comparable to the substrate’s — within a factor of ~2.5 — despite the coating being only 0.01% of the mirror volume. A full calculation accounting for elastic mismatch between coating and substrate materials shows the coating actually dominates.

Measuring mechanical loss

Two complementary approaches are used to characterize coating mechanical loss: disk resonator ring-down measurements (which probe individual material properties) and Fabry–Pérot cavity experiments (which measure the actual displacement noise produced by the coating in an optical readout).

Disk resonators

In a ring-down measurement, a coated silicon disk is excited into a mechanical resonance mode and the quality factor $Q$ is measured from the exponential decay time. The loss angle is simply $\phi = 1/Q$. By comparing the $Q$ of coated and uncoated disks at the same resonant frequency, the coating loss can be extracted.

Our group has used silicon disk resonators extensively. Klochkov et al. (2022) discovered that electric fields can induce mechanical losses in silicon resonators — a previously unrecognized effect that depends on the silicon resistivity and has implications for how disks are driven and read out. Prokhorov et al. (2020) and Abernathy et al. (2016) used ring-down measurements to characterize emissivity coatings (carbon nanotube black and Acktar Black) on silicon wafers, informing the baffle design for Advanced LIGO and the coating choices for LIGO Voyager’s radiative cooling system.

Fabry–Pérot cavity testbeds

A more direct measurement uses two matched Fabry–Pérot cavities whose differential beat-note frequency is sensitive to the mirror displacement noise. By building the cavities from the same materials and operating them side by side, common-mode noise sources (laser frequency noise, seismic motion) cancel in the differential signal, leaving the mirror thermal noise as the dominant contribution.

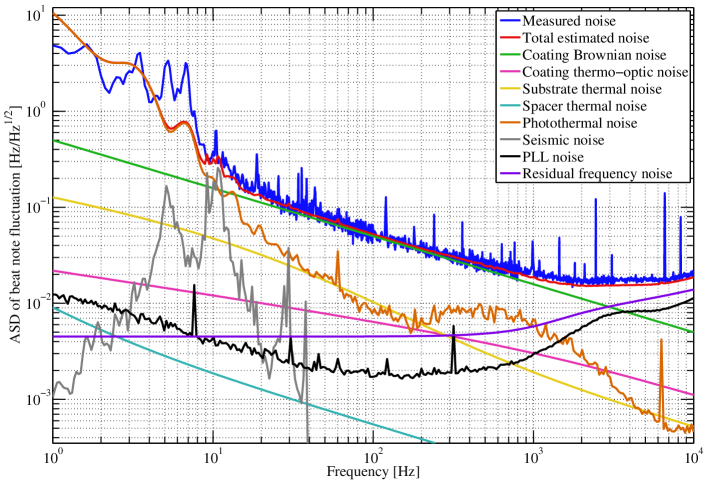

Chalermsongsak et al. (2015) built a pair of rigid fused-silica Fabry–Pérot cavities with silica/tantala coatings and measured broadband coating thermal noise from 50 Hz to 10 kHz. The measured noise was consistent with the predicted coating Brownian noise, with an effective loss angle $\phi_c \approx 4 \times 10^{-4}$ extracted via Bayesian inference. This measurement established the template for all subsequent cavity-based coating noise measurements in the group.

The silicon double cavity

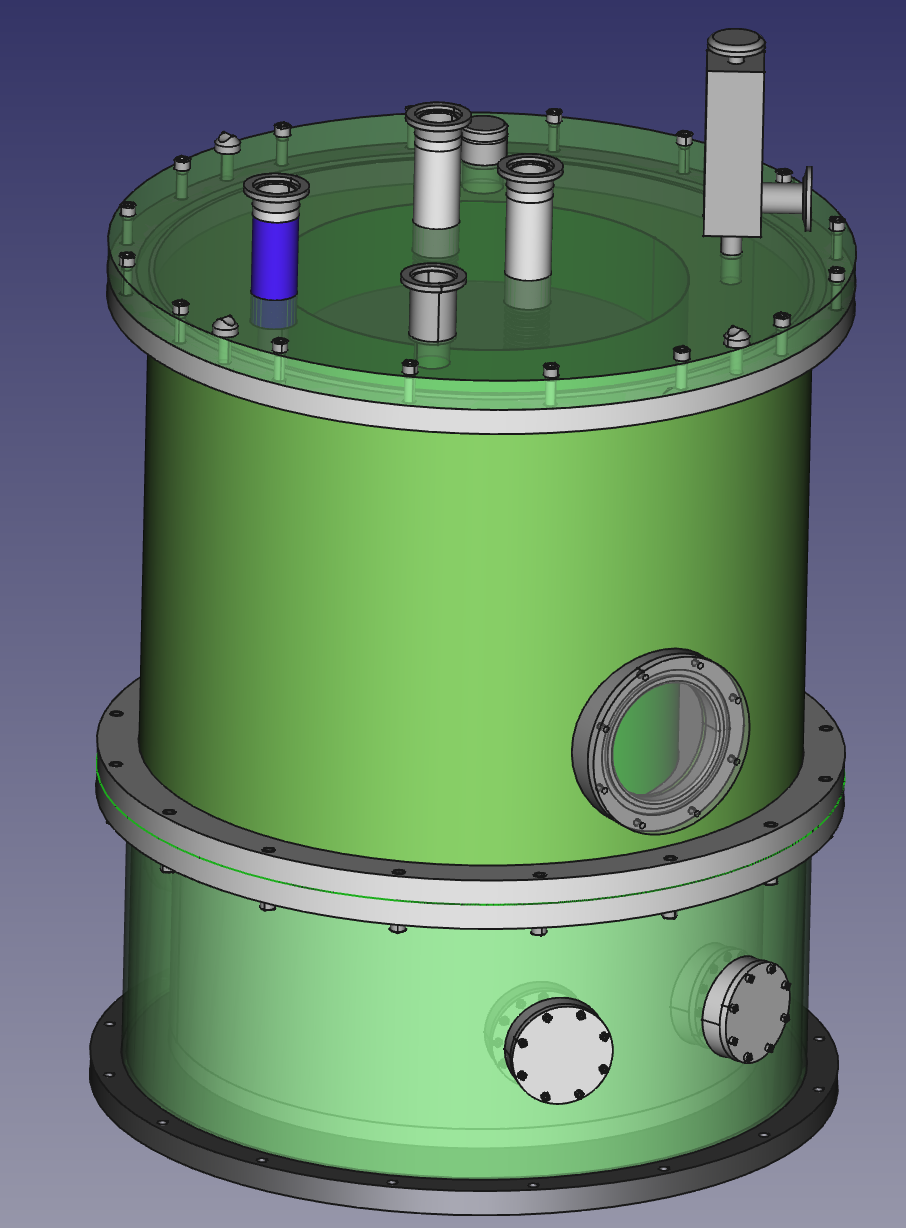

A separate apparatus — a cryogenic silicon Fabry–Pérot cavity — was developed to measure coating thermal noise at LIGO Voyager’s operating conditions: 1550 nm wavelength and 123 K temperature (the zero-crossing of silicon’s coefficient of thermal expansion).

David Yeaton-Massey designed and built the cryostat and cavity system during his PhD (Caltech, 2016). The design uses rigid silicon spacers with high-reflectivity coated silicon mirrors, all cooled inside a custom cryostat. Johannes Eichholz continued development of this apparatus as a postdoc, with support from several SURF students. The goal is to characterize candidate Voyager coatings — including crystalline AlGaAs and amorphous silicon alternatives — under the actual operating conditions they will experience in the detector.

The MIT multi-mode cavity

A complementary approach to direct CTN measurement was developed by Matt Evans and Slawomir Gras at MIT. Their technique uses a folded Fabry–Pérot cavity in which multiple spatial modes (TEM00, TEM02, TEM20) are simultaneously resonant. By comparing the frequency fluctuations of these co-resonating higher-order modes — which sample the mirror surface with different spatial profiles — the coating thermal noise can be extracted with high common-mode rejection of laser frequency noise and seismic motion.

Gras et al. (2017) demonstrated this multi-mode cavity technique and achieved a surface displacement sensitivity of 10⁻¹⁷ m/√Hz in the 30–400 Hz band — directly resolving coating Brownian noise on Advanced LIGO-type tantala/silica coatings. This measurement provided an independent confirmation of the coating loss values used in LIGO’s noise budget.

In a follow-up experiment, Gras & Evans (2018) performed a direct audio-band measurement of coating thermal noise and found that the noise spectrum of ion-beam-sputtered coatings did not follow the expected power-law frequency dependence predicted by the standard structural-damping model. This anomalous spectral shape suggests that the loss mechanism in amorphous coatings may be more complex than a frequency-independent loss angle — potentially involving a distribution of relaxation times in the two-level system ensemble.

The MIT multi-mode cavity and the Caltech rigid cavity / silicon double cavity experiments are complementary: the MIT approach achieves high sensitivity through spatial-mode comparison in a single cavity, while the Caltech approach uses matched cavity pairs for differential readout. Together, they provide cross-validation of coating thermal noise measurements across different frequency bands, coating materials, and operating temperatures.

On the materials side, Yam, Gras & Evans (2015) developed the theory of multi-material (ternary and higher) coating stacks — extending the standard binary (two-material) design to exploit the additional degrees of freedom available with three or more materials. Pierro, Granata, Gras, Evans et al. (2026) recently demonstrated the first experimental ternary coating — a SiN-based stack that achieved 0.82× the thermal noise of a reference binary coating, validating the multi-material optimization approach.

Material systems

The choice of coating material is the single most important lever for reducing coating thermal noise. The key figure of merit is the mechanical loss angle $\phi$ — lower loss means less thermal noise.

Tantala / silica (Ta₂O₅ / SiO₂): The current LIGO baseline. Tantala has $\phi \sim 4 \times 10^{-4}$ and silica has $\phi \sim 5 \times 10^{-5}$. Tantala dominates the total noise because it is the high-index material and carries more strain energy per unit thickness. Titanium-doped tantala (TiO₂:Ta₂O₅) reduces the loss somewhat and is the current post-A+ candidate.

Amorphous silicon (a-Si): Has roughly 10× lower mechanical loss than tantala — making it enormously attractive. However, its optical absorption at 1064 nm is too high for Advanced LIGO’s circulating power levels (~400 kW). At 1550–2050 nm (Voyager wavelengths), absorption is lower and a-Si becomes a viable candidate if absorption can be controlled through optimized deposition and annealing.

AlGaAs crystalline coatings: Substrate-transferred single-crystal GaAs/Al₀.₉₂Ga₀.₀₈As Bragg mirrors. Crystalline materials have fundamentally lower mechanical loss than amorphous ones because the periodic lattice structure provides fewer degrees of freedom for energy dissipation. See the dedicated section below.

Table of measured coating loss angles

| Material | Loss angle φ | Frequency | Temperature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO₂ (amorphous) | ~5 × 10⁻⁵ | Audio band | 300 K | Penn et al. 2003 |

| Ta₂O₅ (amorphous) | ~4 × 10⁻⁴ | Audio band | 300 K | Harry et al. 2002 |

| TiO₂:Ta₂O₅ | ~2 × 10⁻⁴ | Audio band | 300 K | Harry et al. 2006 |

| a-Si:H | ~3 × 10⁻⁵ | Audio band | 300 K | Liu et al. 2014 |

| AlGaAs (bulk, indirect) | 5.33 × 10⁻⁴ | Ring-down | 300 K | Penn et al. (quoted in Gupta 2023) |

| AlGaAs (bulk, direct) | (7.0 ± 1.2) × 10⁻⁴ | 70–600 Hz | 310 K | Gupta, Caltech thesis, 2023 |

| Fused silica substrate | ~1 × 10⁻⁷ | Audio band | 300 K | Numata et al. 2004 |

| Silicon substrate | ~1 × 10⁻⁸ | Audio band | 300 K | McGuigan et al. 1978 |

Note: Values are approximate and depend on deposition conditions, annealing history, and measurement technique. The discrepancy between indirect (ring-down) and direct (cavity) measurements for AlGaAs is discussed in the AlGaAs section.

AlGaAs crystalline coatings

Crystalline AlGaAs coatings — single-crystal GaAs/Al₀.₉₂Ga₀.₀₈As multilayers grown epitaxially on GaAs substrates, then transferred to fused-silica or silicon mirrors by optical contacting — represent a fundamentally different approach to low-noise mirror coatings. Because the atoms sit on a periodic lattice rather than in an amorphous network, the mechanical loss mechanisms are qualitatively different: no dangling bonds, no two-level systems from structural disorder, no medium-range rearrangements.

Thermo-optic noise cancellation

One advantage of crystalline coatings is the ability to engineer the layer structure to cancel thermo-optic noise. In amorphous coatings, temperature fluctuations drive both thermoelastic expansion and thermorefractive index changes, which add constructively. Chalermsongsak et al. (2016) showed that in AlGaAs coatings, the layer thicknesses can be optimized so that the thermoelastic and thermorefractive pathways cancel — the effective thermo-optic coefficient $\bar{\alpha} d - \bar{\beta}\lambda$ can be driven to zero by adjusting the coating structure. This cancellation, demonstrated experimentally in our group, was incorporated into the mirrors used for the direct Brownian noise measurement described below.

Direct measurement of coating Brownian noise

Anchal Gupta’s PhD thesis (Caltech, 2023) describes a direct measurement of coating Brownian noise in AlGaAs crystalline coatings using a tabletop Fabry–Pérot cavity experiment. Two rigid cavities with thermo-optic-optimized AlGaAs mirrors were locked to each other using Pound-Drever-Hall (PDH) frequency stabilization, and the differential beat-note frequency was recorded continuously for over two months during optimal environmental conditions.

The experiment achieved a displacement noise floor of ~2 × 10⁻¹⁸ m/√Hz at 200 Hz. The measured noise from 70 to 600 Hz showed a near-flat (in amplitude spectral density) dominant contribution consistent with coating Brownian noise. A Bayesian inference analysis — fitting the measured beat-note spectrum against a full noise budget including coating Brownian noise, thermo-optic noise, substrate Brownian and thermoelastic noise, seismic coupling, sensing noise, laser frequency noise, laser amplitude noise, and controls shot noise — yielded a bulk loss angle of:

\[\Phi_B = (7.0 \pm 1.2) \times 10^{-4}\]where the limits enclose a 90% confidence interval. An alternative analysis allowing for a frequency-dependent loss angle found $\Phi_B = (5.8 \pm 1.0)(f/100\;\text{Hz})^{0.54 \pm 0.19} \times 10^{-4}$, which better explains the observed roll-off in beat-note frequency noise at higher frequencies.

The factor-of-15 question

The directly measured coating thermal noise is approximately 15 times higher in power spectral density than the level predicted from the indirect loss angle of 5.33 × 10⁻⁴ obtained by Penn et al. from disk resonator Q measurements. (The bulk loss angles themselves differ by a factor of ~1.3: 7.0 × 10⁻⁴ vs. 5.33 × 10⁻⁴; the factor of ~15 in noise power arises after accounting for geometric weighting, frequency dependence, and additional noise sources.) The discrepancy is not yet fully understood, but subsequent work by Yu et al. (2023) identified two additional noise sources in crystalline coatings that a single-polarization cavity experiment cannot distinguish from Brownian noise:

- Global excess noise — spatially correlated displacement noise of unknown origin, with the same 1/f frequency dependence as coating Brownian noise

- Birefringence noise — fluctuations in the refractive index difference between polarization axes

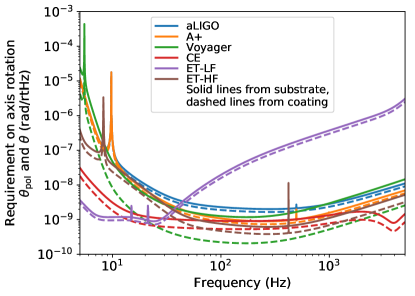

Both of these effects, if present in the Caltech measurement (which used a single polarization and cannot separate them from Brownian noise), could account for much of the observed discrepancy. Michimura et al. (2024) analyzed the birefringence requirements for gravitational-wave detectors using AlGaAs coatings, establishing that coating birefringence fluctuations must be controlled to the ~10⁻¹⁰ rad/√Hz level at 100 Hz.

Computational coating design

Traditional mirror coatings use a quarter-wave stack — every layer is exactly one-quarter of the optical wavelength thick in the material. This maximizes reflectivity for a given number of layers but does not account for thermal noise. Since the back layers (closer to the substrate) contribute more to the total noise than the front layers (see the Hong et al. decomposition above), there is room to optimize: trading a small amount of reflectivity for a significant reduction in thermal noise.

Venugopalan et al. (2024) developed a global optimization framework for multilayer dielectric coatings that jointly minimizes thermal noise, optical absorption, and sensitivity to fabrication tolerances. The optimizer explores the full space of layer thicknesses (not just quarter-wave multiples) using gradient-based methods with multiple random initializations to avoid local minima. A complementary Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis estimates the posterior distribution of coating parameters from measured reflectivity spectra, enabling the extraction of individual layer thicknesses from a completed coating.

This computational approach replaces intuition-based design rules with systematic optimization. For a fixed number of layers and fixed materials, the optimized designs achieve thermal noise reductions of 10–20% compared to quarter-wave stacks, with negligible degradation in reflectivity. Cross-links: Computational Experiment Design.

Deposition, annealing, and scatter

The mechanical properties of amorphous coatings depend sensitively on how they are made. Ion-beam sputtering (IBS) is the standard deposition technique for high-reflectivity optical coatings: a beam of argon or xenon ions sputters material from a target onto the mirror substrate. The resulting film is amorphous, with a structure that depends on the ion energy, deposition rate, substrate temperature, and post-deposition thermal treatment.

Hot-substrate deposition

Vajente et al. (2018) investigated the effect of depositing tantala films at elevated substrate temperatures (up to 500°C) rather than the conventional near-room-temperature process. The films deposited at higher temperatures showed reduced mechanical loss — correlation with Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction measurements suggested that the lower loss was associated with increased medium-range atomic order in the amorphous structure. This work demonstrated that the deposition process itself, not just post-deposition annealing, is a lever for controlling coating loss.

The loss–scatter tension

Post-deposition annealing (typically at 400–600°C) is widely used to reduce coating mechanical loss by allowing the amorphous structure to relax toward a lower-energy configuration. However, Smith et al. (2019) showed that aggressive annealing can increase optical scattering — presumably because partial crystallization produces nanoscale density fluctuations. This creates a fundamental design tension: the annealing protocol that minimizes mechanical loss may not minimize scatter, and vice versa. Finding the optimal compromise requires careful measurement of both properties as a function of annealing temperature and duration.

How annealing changes amorphous structure

Amorphous tantala has no long-range crystalline order, but it does have medium-range order — clusters of atoms arranged in locally regular patterns extending over 1–3 nm. Annealing provides thermal energy for atoms to rearrange, increasing the size and regularity of these medium-range ordered regions. This reduces the density of two-level systems (TLS) — pairs of nearly degenerate atomic configurations separated by low energy barriers — which are the dominant source of mechanical loss at room temperature.

The relationship between medium-range order and mechanical loss has been established through correlations between Raman spectroscopy (which probes vibrational modes sensitive to local structure), X-ray diffraction (which measures the radial distribution function), and ring-down Q measurements. More ordered films consistently show lower loss, up to the point where crystallization begins.

Physics of Mechanical Loss in Thin Films →

Coatings for LIGO Voyager

LIGO Voyager will operate at 123 K — the zero-crossing of silicon’s coefficient of thermal expansion — with silicon test masses at 1550–2050 nm wavelength. This cryogenic operation creates both opportunities and challenges for coatings.

The opportunity: Coating thermal noise scales as $\sqrt{T}$ (from the $k_B T$ factor in the FDT), so cooling from 300 K to 123 K reduces noise by a factor of ~1.6 even with the same coating. If the coating loss also decreases with temperature — as it does for some materials — the improvement can be larger.

The challenge: Coating loss is temperature-dependent, and the dependence is not always monotonic. In amorphous materials, the two-level system (TLS) model predicts loss peaks at specific temperatures where the thermal relaxation rate of TLS matches the measurement frequency. Mapping the full $\phi(T)$ curve from 300 K to 123 K for each candidate coating material is essential for predicting Voyager’s thermal noise performance.

Emissivity coatings for radiative cooling

Voyager’s test masses will be cooled radiatively — no physical contact with a cold stage, which would transmit vibration. The barrel and back surfaces of each mirror need high-emissivity coatings to radiate heat efficiently, but these coatings must not contribute significant thermal noise (they are not on the optical path, but they do add mechanical loss to the substrate).

Prokhorov et al. (2020) measured the mechanical loss of carbon nanotube (CNT) coatings on silicon wafers and found loss levels compatible with Voyager’s noise budget. Abernathy et al. (2016) characterized Acktar Black — a commercially available high-emissivity coating — on silicon, measuring its Young’s modulus via nanoindentation and its mechanical loss via disk resonator ring-down. Both CNT and Acktar Black are candidates for Voyager’s emissivity coatings, with the choice depending on loss at 123 K, adhesion under thermal cycling, and contamination compatibility.

Competing approaches

Coating thermal noise is one of the most actively studied problems in precision measurement. The major alternative strategies include:

Multi-material amorphous stacks: Replacing tantala with lower-loss amorphous materials (hafnia, scandia, alumina, or mixtures) while maintaining adequate reflectivity. The LMA group in Lyon and the Sannio group in Italy have explored titania-doped tantala and hafnia-based coatings.

Nanolayer composites: TNO (Netherlands) and the University of Twente have developed alternating nanolayers of different amorphous materials (e.g., SiO₂/HfO₂ with ~1 nm individual layer thickness) that may suppress TLS-mediated loss by constraining the amorphous structure at the nanoscale.

Epitaxial semiconductors beyond AlGaAs: GaP/AlGaP and other III-V systems are being explored as alternatives that may avoid the birefringence and excess noise issues seen in AlGaAs, while maintaining the low intrinsic loss of crystalline materials.

Longer cavities and larger beams: Coating thermal noise scales as $1/w$ where $w$ is the beam radius. Increasing the beam size or using higher-order Laguerre-Gauss modes reduces the coating noise contribution. However, larger beams require larger mirrors, which increases coating uniformity requirements and cost.

Different detector topologies: Speed meters and other QND readout schemes can reduce the impact of coating thermal noise by measuring a different quadrature of the mirror motion, though these require significant changes to the interferometer design.

Connections to other fields

Frequency standards & optical clocks

Coating thermal noise is the dominant noise source in optical reference cavities used to stabilize lasers for optical atomic clocks. The frequency stability of these clocks — currently reaching parts in 10¹⁸ — is limited by the same coating Brownian noise that limits LIGO. Every advance in low-noise coatings for gravitational-wave detectors directly benefits the precision timekeeping community, and vice versa.

Quantum optomechanics

Coating thermal noise limits the ability to prepare and measure quantum states of macroscopic mechanical oscillators. Experiments aiming to observe quantum superposition of mirror motion, entangle two mechanical oscillators, or test collapse models all require mirrors with the lowest possible thermal noise. The same coatings developed for LIGO are used in tabletop optomechanics experiments worldwide.

Laser fusion & high-power optics

Optical enhancement cavities for laser fusion — such as those being developed through the Blue Laser Fusion / DOE INFUSE collaboration — require coatings that can withstand extreme circulating power densities while maintaining low scatter and absorption. The coating characterization and optimization tools developed for LIGO directly apply.

Cavity QED & quantum computing

Ultra-high-finesse Fabry–Pérot cavities for cavity quantum electrodynamics and quantum computing rely on scatter and absorption losses in the ppm range. The same coating materials and deposition techniques are used, and advances in understanding the relationship between amorphous structure and optical loss feed back into LIGO coating research.

Gravitational-wave astronomy

Coating thermal noise is the primary sensitivity-limiting noise source for Advanced LIGO in the 50–300 Hz band — the frequency range of binary neutron star mergers, the most scientifically productive gravitational-wave sources. Reducing coating noise by a factor of 2 would increase the detection volume by a factor of 8, enabling routine detection of pre-merger signals for multi-messenger astronomy with electromagnetic telescopes.

Our contributions

Group members who have worked on coating thermal noise research include Frank Seifert, Antonio Perreca, Evan Hall, Tara Chalermsongsak, Anchal Gupta, and Andrew Wade, as well as David Yeaton-Massey and Johannes Eichholz on the silicon double cavity apparatus.

- Gautam Venugopalan, Francisco Salces-Cárcoba, Koji Arai, and Rana X. Adhikari. "Global optimization of multilayer dielectric coatings for precision measurements." Optics Express (2024). 10.1364/oe.513807

- Ting Hong, Huan Yang, Eric K. Gustafson, Rana X. Adhikari, and Yanbei Chen. "Brownian thermal noise in multilayer coated mirrors." Physical Review D (2013). 10.1103/physrevd.87.082001

- Tara Chalermsongsak, Frank Seifert, Evan D. Hall, Koji Arai, Eric K. Gustafson, and Rana X. Adhikari. "Broadband measurement of coating thermal noise in rigid Fabry–Pérot cavities." Metrologia (2015). 10.1088/0026-1394/52/1/17

- Tara Chalermsongsak, Evan D. Hall, Garrett D. Cole, David Follman, Frank Seifert, Koji Arai, Eric K. Gustafson, Joshua R. Smith, Markus Aspelmeyer, and Rana X. Adhikari. "Coherent Cancellation of Photothermal Noise in GaAs/Al_(0.92)Ga_(0.08)As Bragg Mirrors." Metrologia (2016). 10.1088/0026-1394/53/2/860

- G. Vajente, A. Ananyeva, G. Billingsley, E. Gustafson, A. Heptonstall, C. Torrie, and R. X. Adhikari. "Effect of elevated substrate temperature deposition on the mechanical losses in tantala thin film coatings." Classical and Quantum Gravity (2018). 10.1088/1361-6382/aaad7c

- Joshua R. Smith, Rana X. Adhikari, Katerin M. Aleman, Adrian Avila-Alvarez, Garilynn Billingsley, Amy Gleckl, Jazlyn Guerrero, Ashot Markosyan, Steven D. Penn, Juan A. Rocha, Dakota Rose, and Robert Wright. "Apparatus to Measure Optical Scatter of Coatings Versus Annealing Temperature." (2019). 10.48550/arxiv.1901.11400

- L. G. Prokhorov, V. P. Mitrofanov, B. Kamai, A. Markowitz, Xiaoyue Ni, and R. X. Adhikari. "Measurement of mechanical losses in the carbon nanotube black coating of silicon wafers." Classical and Quantum Gravity (2020). 10.1088/1361-6382/ab5357

- M. R. Abernathy, N. Smith, W. Z. Korth, R. X. Adhikari, L. G Prokhorov, D. V. Koptsov, and V. P. Mitrofanov. "Measurement of mechanical loss in the Acktar Black coating of silicon wafers." Classical and Quantum Gravity (2016). 10.1088/0264-9381/33/18/185002

- Y. Yu. Klochkov, L. G. Prokhorov, M. S. Matiushechkina, R. X. Adhikari, and V. P. Mitrofanov. "Using silicon disk resonators to measure mechanical losses caused by an electric field." Review of Scientific Instruments (2022). 10.1063/5.0076311

- Yuta Michimura, Haoyu Wang, Francisco Salces-Carcoba, Christopher Wipf, Aidan Brooks, Koji Arai, and Rana X. Adhikari. "Effects of mirror birefringence and its fluctuations to laser interferometric gravitational wave detectors." Physical Review D (2024). 10.1103/physrevd.109.022009

- Venugopalan et al. (2024): Global optimization of multilayer dielectric coatings for precision measurements — computational coating design framework

- Hong et al. (2013): Brownian thermal noise in multilayer coated mirrors — theory of bulk/shear loss decomposition

- Chalermsongsak et al. (2015): Broadband measurement of coating thermal noise in rigid Fabry–Pérot cavities — first cavity CTN measurement in group

- Chalermsongsak et al. (2016): Coherent cancellation of photothermal noise in GaAs/AlGaAs Bragg mirrors — thermo-optic optimization for crystalline coatings

- Vajente et al. (2018): Effect of elevated substrate temperature on tantala coating losses — hot-substrate deposition study

- Smith et al. (2019): Apparatus to measure optical scatter vs annealing temperature — loss–scatter trade-off

- Prokhorov et al. (2020): Measurement of mechanical losses in CNT coatings on silicon — Voyager emissivity coating characterization

- Abernathy et al. (2016): Measurement of mechanical loss in Acktar Black coating on silicon — alternative emissivity coating

- Klochkov et al. (2022): Electric-field-induced mechanical losses in silicon disk resonators — systematic effect in Q measurements

- Michimura et al. (2024): Effects of mirror birefringence and its fluctuations in laser interferometric gravitational wave detectors — requirements for AlGaAs in GW detectors

Key references

Theory:

- H. B. Callen and T. A. Welton, “Irreversibility and Generalized Noise,” Phys. Rev. 83, 34 (1951). — The fluctuation-dissipation theorem.

- Y. Levin, “Internal thermal noise in the LIGO test masses: A direct approach,” Phys. Rev. D 57, 659 (1998). — The direct approach to computing thermal noise.

- T. Hong et al., “Brownian thermal noise in multilayer coated mirrors,” Phys. Rev. D 87, 082001 (2013). — Complete treatment of bulk/shear loss in multilayer stacks.

- P. R. Saulson, “Thermal noise in mechanical experiments,” Phys. Rev. D 42, 2437 (1990). — Foundational application of FDT to mirror suspensions.

Measurement:

- K. Numata, A. Kemery, and J. Camp, “Thermal-noise limit in the frequency stabilization of lasers with rigid cavities,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 250602 (2004). — Broadband cavity CTN measurement technique.

- T. Chalermsongsak et al., “Broadband measurement of coating thermal noise in rigid Fabry–Pérot cavities,” Metrologia 52, 17 (2015). — EGG group cavity measurement.

- A. Gupta, “Next-Generation Technologies for Gravitational Wave Detectors,” Caltech PhD thesis (2023). — Direct measurement of AlGaAs coating Brownian noise.

- S. Gras, H. Yu, W. Yam, D. Martynov, and M. Evans, “Audio-band coating thermal noise measurement with a multi-mode optical resonator,” Phys. Rev. D 95, 022001 (2017). — Multi-mode cavity technique achieving 10⁻¹⁷ m/√Hz surface sensitivity.

- S. Gras and M. Evans, “Direct measurement of coating thermal noise in optical resonators,” Phys. Rev. D 98, 122001 (2018). — Found anomalous power-law spectrum in IBS coatings.

- W. Yam, S. Gras, and M. Evans, “Multi-material coatings with reduced thermal noise,” Phys. Rev. D 91, 042002 (2015). — Ternary and higher multi-material coating optimization theory.

- V. Pierro, V. Granata, …, S. Gras, M. Evans et al., “Experimental realization of optimized ternary mirror coatings,” arXiv:2601.17886 (2026). — First experimental ternary coating (SiN-based, 0.82× noise).

- J. Yu et al., “Excess noise and photo-induced effects in highly reflective crystalline mirror coatings,” Phys. Rev. X 13, 041002 (2023). — Identified global excess noise and birefringence noise in AlGaAs coatings.

Materials:

- G. M. Harry et al., “Thermal noise in interferometric gravitational wave detectors due to dielectric optical coatings,” Class. Quantum Grav. 19, 897 (2002). — Identification of coatings as dominant noise source.

- S. D. Penn et al., “Mechanical loss in tantala/silica dielectric mirror coatings,” Class. Quantum Grav. 20, 2917 (2003). — Tantala loss angle measurement.

- G. D. Cole et al., “Tenfold reduction of Brownian noise in high-reflectivity optical coatings,” Nature Photon. 7, 644 (2013). — Crystalline AlGaAs coatings.

- G. Vajente et al., “Effect of elevated substrate temperature deposition on the mechanical losses in tantala thin film coatings,” Class. Quantum Grav. 35, 075001 (2018). — Hot-substrate deposition.

Reviews:

- R. X. Adhikari, “Gravitational radiation detection with laser interferometry,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 121 (2014). — Comprehensive review including coating noise.

- G. M. Harry and T. Bodiya, eds., Optical Coatings and Thermal Noise in Precision Measurement (Cambridge University Press, 2012). — The reference textbook.