Searching for Unmodeled Signals

Machine learning methods for detecting gravitational-wave transients that don't match existing signal templates, targeting unknown astrophysical phenomena and anomalous events.

Research area

The most transformative discovery in gravitational-wave astronomy will not come from a signal we predicted. Every new observational window in the history of astronomy — radio, X-ray, gamma-ray — has revealed phenomena that nobody anticipated. Gravitational-wave detectors are sensitive to any transient distortion of spacetime, yet the vast majority of search effort targets signals with known waveform templates: compact binary mergers, continuous waves from pulsars, stochastic backgrounds. The “burst” or “unmodeled” search program asks: what else is out there?

Contents:

- Why unmodeled searches matter

- Astrophysical targets

- Detection methods: the community toolkit

- The signal-to-noise challenge

- Machine learning approaches

- The SETI parallel: searching for the unknown

- EGG contributions

- Connection to noise cleaning

- Current results and open questions

- Key references

Why unmodeled searches matter

Template-based matched filtering is the optimal detection strategy when the signal model is known — it is the Neyman-Pearson likelihood ratio test applied to Gaussian noise. The LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA collaboration has used it to build a catalog of ~200 compact binary coalescences through four observing runs. But matched filtering is blind to anything outside the template bank.

The detection statistic for matched filtering is:

\[\rho^2 = 4\,\text{Re}\!\int_0^\infty \frac{\tilde{h}(f)\,\tilde{s}^*(f)}{S_n(f)}\,df\]where $\tilde{h}(f)$ is the template, $\tilde{s}(f)$ is the data, and $S_n(f)$ is the noise power spectral density. This integral is maximized when the template exactly matches the signal — and can return essentially zero even for a loud signal with the “wrong” morphology. A gravitational-wave burst from a core-collapse supernova, a cosmic string cusp, or an entirely unknown source could pass through the matched-filter pipeline undetected.

Unmodeled searches sacrifice some sensitivity (the ~2x SNR penalty noted above) in exchange for generality: the ability to detect any transient excess power in the detector data, regardless of its waveform morphology. This is the same trade-off faced by every branch of observational science — you can look for what you expect, or you can look for what you don’t.

This is the street-light effect applied to fundamental physics. We search where the templates are — compact binary mergers, continuous waves — because that’s where we’re most sensitive, and the rewards have been spectacular. But the most transformative discoveries in astronomy have always come from looking away from the lamp post. Radio pulsars, gamma-ray bursts, and fast radio bursts were all found by instruments that were not optimized to detect them. The gravitational-wave burst program is a deliberate decision to search in the dark, accepting a sensitivity penalty for the chance of finding something genuinely new.

Astrophysical targets

Several known source types produce gravitational waves with poorly modeled or entirely unpredicted waveforms.

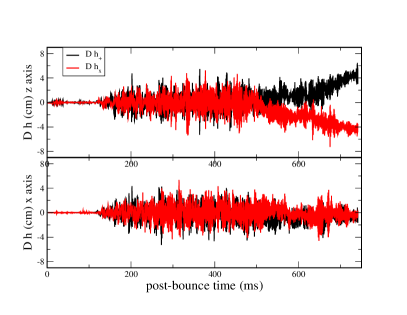

Core-collapse supernovae

When a massive star ($\gtrsim 8\,M_\odot$) exhausts its nuclear fuel, the iron core collapses in ~100 ms to form a proto-neutron star. The gravitational-wave emission depends on the turbulent dynamics of the collapse — convection, the standing accretion shock instability (SASI), neutrino-driven outflows, and rotational effects. Numerical simulations produce diverse waveform morphologies that depend sensitively on progenitor mass, rotation rate, magnetic field strength, and the nuclear equation of state.

No template bank can span the physical parameter space. Detection of a Galactic core-collapse supernova in gravitational waves would probe the engine of the explosion, complementing neutrino and electromagnetic observations in a way that no other messenger can.

Post-merger remnants

After two neutron stars merge, the remnant — if it does not immediately collapse to a black hole — oscillates at several kHz with quasi-periodic structure set by the nuclear equation of state. These signals are short-lived (tens of milliseconds), broadband, and only partially modeled. The frequency of the dominant oscillation mode encodes the equation of state of ultra-dense matter, making detection a high priority even at modest SNR.

Cosmic string cusps and kinks

Topological defects from symmetry-breaking phase transitions in the early universe would produce gravitational-wave bursts with characteristic power-law spectra. The waveform shape is known analytically — cusps produce $h(f) \propto f^{-4/3}$, kinks produce $h(f) \propto f^{-5/3}$ — but the rate, amplitude distribution, and string tension $G\mu$ are unknown. A single detection would be direct evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model.

Magnetar flares

Giant flares from magnetars (neutron stars with $B \sim 10^{15}$ G) release $\sim 10^{46}$ erg in gamma rays on timescales of ~0.1 s. The associated crustal oscillations may excite gravitational waves at frequencies of hundreds of Hz to several kHz. The 2004 giant flare from SGR 1806-20 was visible across the galaxy in electromagnetic radiation; a gravitational-wave counterpart would constrain the neutron star interior.

The truly unknown

This is the most important category. Pulsars were discovered by accident (Jocelyn Bell, 1967). Gamma-ray bursts were discovered by accident (Vela satellites, 1967). Fast radio bursts were discovered by accident (Lorimer et al., 2007, in archival pulsar survey data — nobody was looking for them). If an analogous phenomenon exists in the gravitational-wave spectrum — millisecond-duration transients from an unknown source class — template-based searches would miss it entirely, because there would be no template to match. The gravitational-wave spectrum has been open for barely a decade. The probability that we have already cataloged every source type is zero.

Detection methods: the community toolkit

The gravitational-wave burst search program uses a diverse set of algorithms, each with different strengths. No single pipeline is optimal for all signal morphologies — the LVK runs multiple searches in parallel and combines their results.

Excess power: coherent WaveBurst (cWB)

Coherent WaveBurst identifies clusters of excess energy in the time-frequency plane across multiple detectors simultaneously. The algorithm:

- Decomposes each detector’s data stream using a wavelet transform (Wilson-Daubechies-Meyer wavelets)

- Identifies time-frequency pixels with energy above a threshold

- Clusters neighboring pixels into candidate events

- Applies a coherence constraint: a real gravitational-wave signal must be consistent with a single sky location and polarization state across all detectors

The coherence test is the key discriminant. Instrumental glitches — even loud ones — generally do not produce consistent responses across geographically separated detectors. cWB has successfully detected compact binary mergers (it independently identified GW150914, the first detection) and provides the primary all-sky burst search in LVK observing runs.

Bayesian signal vs. glitch: BayesWave

BayesWave takes a fundamentally different approach. It models each candidate transient as a superposition of sine-Gaussian wavelets and uses Bayesian model selection to distinguish three hypotheses:

- Signal: A coherent gravitational-wave transient present in all detectors

- Glitch: An independent instrumental artifact in one or more detectors

- Noise: Gaussian noise with no transient

The Bayes factor between the signal and glitch models serves as the detection statistic. BayesWave can also reconstruct the waveform of a detected signal without assuming a model — useful for parameter estimation of novel sources.

oLIB: Q-transform coincidence with Bayesian follow-up

oLIB (Lynch et al. 2017) combines fast trigger generation with Bayesian evidence evaluation. The pipeline first identifies time-frequency transients using the Omicron Q-transform (see below), then requires coincidence between detectors, and finally evaluates Bayesian evidence ratios using LALInferenceBurst. This two-stage architecture — fast triggering followed by expensive Bayesian analysis only on promising candidates — balances computational cost against sensitivity. oLIB provides an independent burst search complementary to cWB and BayesWave.

X-Pipeline: externally triggered coherent analysis

X-Pipeline (Sutton et al. 2010) is designed for burst searches triggered by external observations — gamma-ray bursts, magnetar flares, or neutrino alerts. When the sky position and time window are known from an electromagnetic or neutrino trigger, the analysis can fold in the known antenna pattern response, gaining coherence power that all-sky searches cannot exploit. This makes X-Pipeline particularly powerful for multi-messenger follow-up, where even a sub-threshold gravitational-wave signal correlated with an observed astrophysical event can be significant.

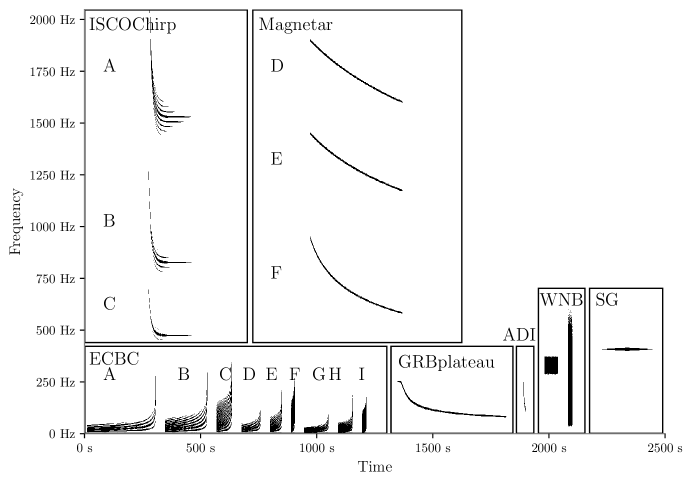

STAMP / PySTAMPAS: long-duration burst searches

Long-duration gravitational-wave transients — lasting seconds to hundreds of seconds — require different algorithms than millisecond bursts. STAMP (Thrane et al. 2011) and its successor PySTAMPAS construct cross-power spectrograms between detector pairs and search for tracks of excess cross-correlation using pattern-recognition algorithms (Zebragard for seed-based clustering, Lonetrack for seedless). These pipelines are essential for sources like post-merger magnetar spindown, fallback accretion onto newly formed black holes, or long-lived neutron star oscillations, where the signal duration exceeds typical glitch timescales.

Omicron: the shared trigger infrastructure

Nearly all burst pipelines depend on Omicron (Robinet et al. 2020) as their trigger-generation front end. Omicron tiles the time-frequency plane using the Q-transform — a multiresolution decomposition where each tile’s quality factor $Q$ determines the trade-off between time and frequency resolution. High-$Q$ tiles resolve narrow spectral features; low-$Q$ tiles resolve short transients. The resulting trigger lists feed into oLIB, Gravity Spy glitch classification, detector characterization workflows, and data quality vetoes. Omicron is infrastructure — not a search algorithm itself, but a foundation on which most searches are built.

The Q-transform: shared time-frequency representation

The Q-transform is a constant-$Q$ variant of the short-time Fourier transform. For a given quality factor $Q$, each basis function is a sinusoid windowed by a Gaussian with duration $\tau = Q/(2\pi f_0)$, where $f_0$ is the central frequency. The key property is that the time-frequency uncertainty product is controlled by $Q$:

\[\Delta t \cdot \Delta f = \frac{1}{2\pi}\left(1 + \frac{1}{Q^2}\right)^{1/2}\]At high $Q$, tiles are narrow in frequency and long in time — good for quasi-monochromatic signals like neutron star ringdowns. At low $Q$, tiles are broad in frequency and short in time — good for impulsive bursts. By searching over a range of $Q$ values (typically $Q \in [4, 100]$), the Q-transform adapts its resolution to match whatever signal morphology is present in the data. This is why multiple burst pipelines — Omicron, oLIB, and BayesWave’s wavelet decomposition — all use variants of this idea: the Q-transform is the natural basis for signals of unknown duration and bandwidth.

How excess power detection works

The simplest burst detection statistic is the excess power statistic. For a time-frequency tile of duration $\Delta t$ and bandwidth $\Delta f$, the expected noise energy is:

\[\langle E_\text{noise} \rangle = 2\,\Delta t\,\Delta f\,S_n(f)\]where $S_n(f)$ is the one-sided noise power spectral density. A gravitational-wave signal adds energy:

\[E_\text{signal} = \int_{\Delta t}\int_{\Delta f} |h(t,f)|^2\,dt\,df\]The detection statistic is the ratio $E_\text{measured}/\langle E_\text{noise}\rangle$. For Gaussian noise, this ratio follows a $\chi^2$ distribution, and deviations indicate either a signal or a non-Gaussian noise artifact (glitch). The challenge is that real LIGO data contains ~1 glitch per minute with excess power comparable to or exceeding astrophysical signals of interest.

Coherent multi-detector analysis resolves this ambiguity by requiring that excess power appears consistently across detectors. The null stream — a linear combination of detector outputs that cancels any gravitational-wave signal for a given sky direction — should contain only noise. Significant energy in the null stream indicates a glitch rather than a signal.

The signal-to-noise challenge

The fundamental difficulty of burst searches is separating astrophysical transients from instrumental glitches. LIGO data contains non-Gaussian transient artifacts at a rate of roughly one per minute — “blips,” “scattered light” arches, “tomtes,” “whistles,” and dozens of other morphological types cataloged by the Gravity Spy citizen science project (Zevin et al. 2017).

Matched filtering suppresses glitches naturally: a glitch that does not resemble a binary chirp produces a small matched-filter output. Burst searches have no such advantage. Every glitch is a potential false alarm. The result: burst searches operate at effective SNR thresholds of 10-15, compared to ~8 for matched filtering. In terms of detectable volume, this corresponds to a factor of $(15/8)^3 \approx 7\times$ fewer sources.

Improving burst search sensitivity therefore requires either:

- Reducing the glitch rate (noise cleaning, detector commissioning)

- Better glitch-signal discrimination (machine learning, multi-detector consistency)

- Both simultaneously

Machine learning approaches

Machine learning is reshaping gravitational-wave burst searches across the community, from production pipelines running in LVK observing runs to experimental approaches exploring the frontiers of anomaly detection.

MLy: production ML for O4

MLy (Skliris et al. 2024) is a convolutional neural network pipeline deployed in the LVK’s O4 observing run. Trained on multi-detector spectrograms with diverse injection morphologies, MLy reportedly achieves sensitivity improvements approaching an order of magnitude for short single-cycle waveforms compared to cWB, while maintaining comparable false alarm rates. Its deployment as a production search — not just a proof of concept — marks a transition point: ML is no longer supplementary to traditional burst searches but competitive with them.

GWAK: semi-supervised anomaly detection

GWAK (Raikman et al. 2024) takes a different approach, using recurrent autoencoders trained in a semi-supervised framework. The network learns to reconstruct multi-detector data from several classes — Gaussian noise, known glitch types, and compact binary signals — and flags anomalies as data segments with high reconstruction error that don’t fit any known category. Applied to O3 data, GWAK successfully identified known compact binary coalescences and showed robustness to high-glitch-rate data segments, demonstrating that anomaly-based detection can work in realistic noise environments.

Anomaly detection with autoencoders

Neural networks trained on detector noise learn what “normal” looks like; deviations flag potential signals for follow-up. Autoencoders and variational autoencoders trained on spectrograms of detector noise identify anomalous time-frequency patterns by using reconstruction error as a detection statistic. If the autoencoder cannot reconstruct a segment of data well, the residual may contain a signal — or a novel glitch type.

This complements the neural network noise cleaning work: the same understanding of noise couplings that enables subtraction also enables detection of anomalies that do not fit the noise model.

Signal morphology classification

Convolutional networks classify transient events by their time-frequency structure, separating known glitch types (blips, scattered light, tomtes, koi fish) from potential astrophysical candidates. The Gravity Spy project (Zevin et al. 2017) demonstrated this for glitch classification with >97% accuracy on 22 morphological classes; we extend this toward separating glitches from signals of unknown morphology — a harder problem, since “unknown signal” is not a well-defined class.

Multi-detector consistency

Genuine signals must appear consistently across detectors (accounting for antenna patterns and time delays); instrumental artifacts do not. ML methods that exploit multi-detector correlations — training on the joint time-frequency representation from all detectors simultaneously — can improve detection confidence without assuming a signal model. This is the ML analogue of the coherence constraint in cWB, but potentially more sensitive because a neural network can learn subtle consistency patterns that a hand-crafted statistic misses.

Learned detection statistics

Rather than hand-crafting a detection statistic (like excess power or coherent energy), a neural network can learn the statistic that maximizes detection probability for a broad class of signal morphologies. When trained on physically diverse waveform catalogs from numerical simulations — including supernovae, post-merger remnants, and cosmic strings — these networks can generalize to morphologies not in the training set, provided they share statistical features with the training distribution.

The ML approaches to burst detection span a conceptual spectrum. At one end is pure anomaly detection — flag anything that doesn’t look like noise, with no signal assumptions. At the other end is the learned matched filter — train a network on specific waveform families to approximate optimal filtering without explicit templates. In between lies supervised classification, which separates known glitch categories from potential signals. Each approach makes different trade-offs between sensitivity and generality, and current research is exploring how to combine them hierarchically: broad anomaly detection as a first pass, followed by targeted classification and matched filtering for candidates that survive.

Anomaly detection vs. classification vs. learned matched filter

The three ML strategies for burst detection correspond to different points on the sensitivity-generality trade-off:

Anomaly detection (autoencoders, GWAK): Train only on noise and known artifacts. Anything the model can’t reconstruct is flagged. Maximum generality — can detect truly novel signals — but lowest sensitivity, since the detection threshold is set by the model’s reconstruction ability rather than signal properties.

Supervised classification (Gravity Spy, MLy): Train on labeled examples of both noise artifacts and injected signals of various morphologies. Higher sensitivity for signal types in the training set, but blind to morphologies not represented. Performance degrades when the test distribution shifts from training.

Learned matched filter (neural network detection statistics): Train a network to approximate the likelihood ratio between signal-present and noise-only hypotheses for a broad waveform catalog. Highest sensitivity for signals within the training distribution — potentially approaching matched-filter optimality — but inherits the template-bank problem: sensitivity to novel morphologies depends on how well the training catalog spans the true signal space.

The community is moving toward hierarchical architectures that use anomaly detection as a first trigger, followed by classification for glitch rejection, and learned matched filtering for detection significance estimation. This mirrors the structure of existing pipelines like oLIB (Omicron trigger → coincidence → Bayesian follow-up) but with ML components at each stage.

The SETI parallel: searching for the unknown

The search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) and the gravitational-wave burst program share a structural identity that is underappreciated in both communities. Both face the same fundamental problem: detecting unknown signals in non-Gaussian noise, where the signal morphology cannot be specified in advance. The algorithmic solutions developed independently by the two fields are converging.

The cosmic haystack

Wright et al. (2018) quantified the SETI search space as an 8-dimensional parameter volume — frequency, bandwidth, sky position, distance, polarization, modulation, repetition, and transmitter power — and showed that decades of radio SETI have explored a vanishingly small fraction of it, comparable to searching a hot tub’s worth of water from Earth’s oceans. The gravitational-wave burst search space is analogously vast: signal duration, frequency content, sky position, polarization, waveform morphology, and repetition pattern define a parameter volume that current searches sample sparsely. We are early in both searches.

SETI algorithms and GW parallels

The dominant SETI search algorithm, turboSETI, is essentially a matched filter for narrowband signals with linear Doppler drift — the SETI analogue of searching for continuous gravitational waves from known pulsars. Just as the GW community has recognized the need for unmodeled burst searches alongside template-based CBC searches, the SETI community is developing broadband anomaly detection methods: HDBSCAN clustering for finding structure in radio spectrograms without assuming signal morphology, and deep learning classifiers for technosignatures (Ma et al. 2023) that parallel the ML approaches described above.

LIGO as SETI instrument

Sellers et al. (2022) made the connection explicit: unmodeled gravitational-wave searches are inherently searches for the unknown, and any sufficiently advanced civilization producing detectable gravitational waves would constitute a technosignature. More practically, the vetting procedures for anomalous candidates share the same logical framework. The blc1 candidate signal from Breakthrough Listen (Sheikh et al. 2021) was vetted using ON/OFF-source cadence — pointing at Proxima Centauri, then away, to test whether the signal tracks the source. Gravitational-wave candidate vetting uses multi-detector coherence tests that are structurally identical: if the signal is astrophysical, it must appear consistently across detectors; if it is instrumental, it will not.

How blc1 vetting maps onto GW candidate vetting

The blc1 signal near 982 MHz appeared in Breakthrough Listen observations of Proxima Centauri. The vetting framework (Sheikh et al. 2021) used a systematic cadence:

- ON-source observation: Point at the target. Record data. Is the signal present?

- OFF-source observation: Point away. Is the signal still present? If yes → likely RFI (radio frequency interference), not astrophysical.

- Consistency tests: Does the signal’s frequency drift match the expected Doppler signature of Proxima Centauri? Does it appear in multiple beams?

Gravitational-wave candidate vetting follows the same logic with different implementation:

- Multi-detector coincidence: Is the signal present in both LIGO Hanford and LIGO Livingston (and Virgo, KAGRA)? If only one detector → likely a glitch.

- Null stream test: Construct a linear combination of detector outputs that cancels any real gravitational-wave signal. If significant energy remains in the null stream → likely instrumental.

- Time-slide background: Shift detector data streams by unphysical time offsets. If the candidate’s significance is comparable to time-slide coincidences → consistent with noise.

In both cases, the core principle is the same: a real signal produces correlated responses in independent measurement channels; an artifact does not. The blc1 signal was ultimately attributed to RFI. If a GW burst candidate passed all consistency tests but matched no known source model, the community would face the same interpretive challenge SETI faces with unexplained candidate signals.

EGG contributions

-

Noise reduction for burst searches — Ormiston et al. 2020 (PRR 2, 033066): DeepClean neural network subtracts non-linear noise couplings from the gravitational-wave channel, directly improving the signal-to-noise ratio for burst searches by reducing the transient artifact rate.

-

Nonlinear noise cleaning — Yu & Adhikari 2022 (Frontiers in AI 5, 811563): Convolutional neural network captures bilinear and higher-order noise couplings that linear methods miss, extending the noise subtraction framework to the non-Gaussian artifacts that dominate burst search backgrounds.

-

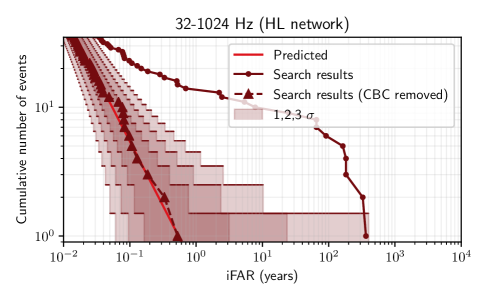

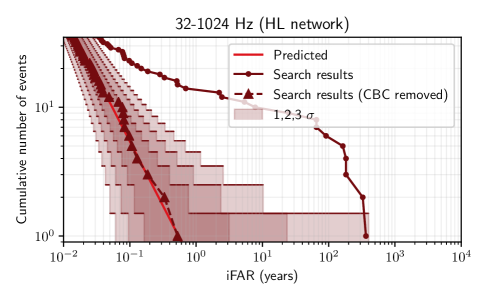

LVK short-duration burst search — Group members participated in the O3 all-sky short burst search (PRD 104, 122004), which set the most stringent upper limits on generic gravitational-wave transients.

-

LVK long-duration burst search — Group members participated in the O3 long-duration burst search (PRD 104, 102001), covering signal durations from 2 to 500 seconds using STAMP/PySTAMPAS and cWB-long.

-

O3 magnetar burst search — Group members participated in the search for gravitational-wave transients associated with magnetar bursts in O3 (ApJ, 2024), targeting triggered searches around known magnetar flare events.

-

O2 magnetar burst search — Group members participated in the O2 magnetar burst search (ApJ 874, 163), an earlier iteration using X-Pipeline for externally triggered analysis.

-

Detector characterization for GW150914 — Group members participated in characterizing transient noise relevant to the first gravitational-wave detection (CQG 33, 134001), establishing the data quality framework used in all subsequent burst searches.

Connection to noise cleaning

The link to neural network noise cleaning is direct and practical. DeepClean and related noise-subtraction networks reduce the rate of non-Gaussian transient artifacts by identifying and removing noise coupled from auxiliary channels. Every glitch removed from the data is one fewer false alarm in the burst search.

In O3, glitch subtraction improved the effective duty cycle for burst searches by reducing the fraction of data flagged as contaminated. For O4 and beyond, the combination of improved noise subtraction (via neural network noise cleaning and digital twin diagnostics) and ML-based burst detection could push unmodeled search sensitivity significantly closer to matched-filter performance.

The RL feedback control project also contributes: better feedback controllers reduce the coupling of environmental disturbances into the gravitational-wave channel, suppressing glitch production at the source rather than in post-processing.

Current results and open questions

The LVK O3 all-sky burst search (Abbott et al. 2021) found no statistically significant evidence for gravitational-wave bursts beyond identified compact binary mergers. This null result sets the most stringent upper limits on the rate of generic gravitational-wave transients, with $h_\text{rss}$ (root-sum-squared strain) sensitivities in the range $10^{-22}$-$10^{-21}$ Hz$^{-1/2}$ depending on frequency and signal morphology. For a Galactic core-collapse supernova at 10 kpc, current detectors would be sensitive to gravitational-wave energies of $\sim 10^{-8}\,M_\odot c^2$ — well above most simulation predictions, which cluster around $10^{-9}$-$10^{-10}\,M_\odot c^2$.

Open questions

-

False alarm estimation without a signal model. Without a waveform template, how do you estimate the false alarm probability of a detection? Time slides (shifting one detector’s data relative to another) provide empirical background estimates, but the non-stationarity of real detector noise means the background changes on timescales of hours. ML-based approaches to background estimation — learning the time-varying glitch rate and morphology — could improve on fixed time-slide methods.

-

Interpretability. If an ML system flags a candidate, how do we understand why it was flagged? Astrophysical follow-up requires physical interpretation, not just a detection statistic. Saliency maps, attention weights, and prototype-based explanations can help, but the gap between “statistically significant anomaly” and “astrophysical source with physical parameters” remains wide.

-

Training data and domain shift. Anomaly detection systems need training data that spans the full range of non-astrophysical artifacts. Detector glitch populations evolve over time as hardware changes, commissioning progresses, and environmental conditions shift. Online learning and continual adaptation may be necessary to maintain performance across observing runs.

-

Sensitivity vs. generality trade-off. There is an inherent tension between search sensitivity (which improves with signal-specific assumptions) and generality (which requires making fewer assumptions). A hierarchical approach — broad anomaly detection as a first pass, followed by targeted follow-up with signal-specific tools — may navigate this trade-off, but the optimal architecture is an open design problem.

-

Post-detection protocol for anomalous signals. If an unmodeled burst candidate passes all consistency tests but matches no known astrophysical source class, what happens next? The SETI community has the IAA Post-Detection Protocol — a formal framework for verification and announcement of a candidate technosignature. The gravitational-wave community has well-established procedures for CBC detections but no equivalent protocol for truly anomalous (non-CBC, non-glitch) transients. What confidence threshold triggers multi-messenger follow-up? Who decides that a candidate is “interesting enough” to announce? These questions become urgent as search sensitivity improves.

The null stream test

The null stream is the most powerful consistency test available to burst searches. For a network of $N$ detectors, the gravitational-wave signal has only two independent polarization components ($h_+$ and $h_\times$). With three or more detectors, one can construct at least one linear combination of the detector outputs that cancels any gravitational-wave signal from a given sky direction:

\[\mathbf{n}(t) = \sum_i w_i\,d_i(t - \Delta t_i)\]where the weights $w_i$ are chosen so that $\sum_i w_i F_i^{+,\times} = 0$ for the antenna pattern functions $F_i^{+,\times}$ at the candidate sky position, and $\Delta t_i$ accounts for the time delay between detectors. A genuine gravitational-wave signal produces zero energy in the null stream (up to noise fluctuations); a glitch or artifact in a single detector produces significant null-stream energy. The null stream energy ratio — signal energy divided by null energy — provides a powerful discriminant that requires no signal model, only the assumption that the signal is a gravitational wave from a specific sky direction.

Key references

LVK burst search results

-

LVK Collaboration, “All-sky search for short gravitational-wave bursts in the third Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo run,” PRD 104, 122004 (2021). arXiv:2107.03701 — O3 short-duration burst search: no novel sources detected, best upper limits to date.

-

LVK Collaboration, “All-sky search for long-duration gravitational-wave bursts in the third Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo run,” PRD 104, 102001 (2021). arXiv:2107.13796 — O3 long-duration burst search covering 2-500 s duration signals.

-

LVK Collaboration, “All-sky search for short gravitational-wave bursts in the first part of the fourth LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA observing run,” (2025). arXiv:2507.12374 — O4a results with improved sensitivity.

-

LVK Collaboration, “Search for gravitational-wave transients associated with magnetar bursts in Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo data from the third observing run,” ApJ (2024). DOI:10.3847/1538-4357/ad27d3 — O3 targeted search around magnetar flare events using X-Pipeline.

Burst search algorithms

-

Klimenko et al., “Method for detection and reconstruction of gravitational wave transients with networks of advanced detectors,” PRD 93, 042004 (2016). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.93.042004 — Coherent WaveBurst (cWB) algorithm.

-

Cornish & Littenberg, “BayesWave: Bayesian inference with gravitational wave transients,” CQG 32, 135012 (2015). DOI:10.1088/0264-9381/32/13/135012 — BayesWave algorithm.

-

Lynch et al., “Information-theoretic approach to the gravitational-wave burst detection problem,” PRD 95, 104046 (2017). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.95.104046 — oLIB pipeline: Q-transform trigger generation followed by Bayesian model selection.

-

Sutton et al., “X-Pipeline: an analysis framework for burst searches in gravitational wave data,” New Journal of Physics 12, 053034 (2010). DOI:10.1088/1367-2630/12/5/053034 — X-Pipeline for externally triggered coherent burst searches.

-

Robinet et al., “Omicron: a tool to characterize transient noise in gravitational-wave detectors,” SoftwareX 12, 100620 (2020). DOI:10.1016/j.softx.2020.100620 — Q-transform based trigger generation infrastructure used across LVK burst pipelines.

Core-collapse supernovae

-

Mezzacappa & Zanolin, “Gravitational Waves from Neutrino-Driven Core Collapse Supernovae: Predictions, Detection, and Parameter Estimation,” (2024). arXiv:2401.11635 — Review of CCSN gravitational-wave emission and detection prospects.

-

Abdikamalov et al., “Gravitational Waves from Core-Collapse Supernovae,” in Handbook of Gravitational Wave Astronomy (Springer, 2022). DOI:10.1007/978-981-16-4306-4_21 — Comprehensive review.

Machine learning for burst detection

-

Zevin et al., “Gravity Spy: Integrating advanced LIGO detector characterization, machine learning, and citizen science,” CQG 34, 064003 (2017). DOI:10.1088/1361-6382/aa5cea — Glitch classification with CNNs and citizen science.

-

Cuoco et al., “Enhancing gravitational-wave science with machine learning,” Machine Learning: Science and Technology 2, 011002 (2021). DOI:10.1088/2632-2153/abb93a — Review of ML applications in GW science including burst detection.

-

Raikman et al., “GWAK: Gravitational-Wave Anomalous Knowledge with Recurrent Autoencoders,” (2024). arXiv:2309.11537 — Semi-supervised anomaly detection applied to O3 data.

-

Ormiston et al., “Noise Reduction in Gravitational-wave Data via Deep Learning,” PRR 2, 033066 (2020). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.033066 — DeepClean noise subtraction framework.

-

Yu & Adhikari, “Nonlinear noise cleaning in gravitational-wave detectors with convolutional neural networks,” Frontiers in AI 5, 811563 (2022). DOI:10.3389/frai.2022.811563 — CNN-based bilinear noise coupling subtraction.

The SETI parallel

-

Wright et al., “How Much SETI Has Been Done? Finding Needles in the n-Dimensional Cosmic Haystack,” AJ 156, 260 (2018). DOI:10.3847/1538-3881/aae099 — Quantitative framework for SETI search completeness; the “cosmic haystack” analysis.

-

Sheikh et al., “Analysis of the Breakthrough Listen signal of interest blc1 with a technosignature verification framework,” Nature Astronomy 5, 1148 (2021). DOI:10.1038/s41550-021-01508-8 — Systematic vetting of the blc1 candidate; ON/OFF-source cadence framework.

-

Sellers et al., “Searches of gravitational-wave data for continuous-wave signals and stochastic backgrounds as searches for extraterrestrial intelligence,” (2022). arXiv:2212.02065 — Argument that GW searches are inherently SETI searches.

-

Ma et al., “A deep-learning search for technosignatures from 820 nearby stars,” Nature Astronomy 7, 492 (2023). DOI:10.1038/s41550-023-01934-0 — Deep learning applied to Breakthrough Listen data.

Cosmic strings

- LVK Collaboration, “Constraints on cosmic strings using data from the third Advanced LIGO-Virgo observing run,” PRL 126, 241102 (2021). arXiv:2101.12248 — Upper limits on cosmic string tension from O3 burst and stochastic searches.