Precision Optomechanical Platforms

Kilogram-scale mirrors with attometer-level readout sensitivity, repurposed from gravitational-wave detection to probe quantum mechanics at macroscopic scales and test quantum-gravity predictions.

Gallery

Research area

LIGO’s 40 kg mirrors, suspended as pendulums and read out by laser cavities with attometer-level displacement sensitivity, are among the most sensitive mechanical sensors ever constructed. In 2020, the LIGO team demonstrated that these kilogram-mass objects exhibit measurable quantum behavior — the radiation pressure of light induces correlated fluctuations in mirror position and reflected light phase, producing quantum correlations between the light field and the mirror motion. This measurement, reaching 3 dB below the standard quantum limit, established LIGO as the world’s most massive quantum optomechanical system and opened a new regime for testing quantum mechanics, gravity, and their intersection at macroscopic scales.

Contents:

- The standard quantum limit

- LIGO as a quantum optomechanical system

- Quantum correlations: the Yu et al. measurement

- Feedback cooling to the ground state

- From detector to quantum laboratory

- Why kilogram-scale? Competing platforms

- Technical challenges

- Connections to other EGG projects

- Our contributions

- Current status and open questions

- Key references

- Further reading

The standard quantum limit

Any continuous position measurement is constrained by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Measuring a mirror’s position more precisely requires more photons, which exert more radiation pressure, which kicks the mirror, which adds noise to the next measurement. This trade-off between shot noise (from photon counting statistics) and quantum radiation pressure noise (QRPN, from photon momentum transfer) defines the standard quantum limit (SQL):

\[S_x^\text{SQL}(f) = \frac{2\hbar}{m(2\pi f)^2}\]where $m$ is the mirror mass and $f$ is the measurement frequency. For a 40 kg LIGO mirror at 50 Hz, this gives $S_x^\text{SQL} \approx 3 \times 10^{-20}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ — about 20,000 times smaller than the diameter of a proton.

Derivation of the SQL

Consider a Michelson interferometer with arm power $P$ and mirror mass $m$. The two quantum noise contributions to displacement sensitivity are:

Shot noise (measurement imprecision):

\[S_x^\text{shot}(f) = \frac{\hbar c \lambda}{16\pi P}\]This is white (frequency-independent) and decreases with increasing power.

Radiation pressure noise (measurement back-action):

\[S_x^\text{QRPN}(f) = \frac{16\pi \hbar P}{m^2 c \lambda (2\pi f)^4}\]This rises steeply at low frequencies (as $1/f^4$ for free masses) and increases with power. The total quantum noise is the sum:

\[S_x^\text{total}(f) = S_x^\text{shot} + S_x^\text{QRPN}\]At each frequency, there exists an optimal power that minimizes $S_x^\text{total}$. Setting $\partial S_x^\text{total}/\partial P = 0$ yields $S_x^\text{SQL}(f) = 2\hbar / [m(2\pi f)^2]$. The SQL represents equal contributions from shot noise and radiation pressure noise — it is not a hard limit but rather the best sensitivity achievable with a simple (uncorrelated) measurement strategy.

The SQL is not a fundamental limit. It can be surpassed by introducing correlations between the light’s amplitude and phase quadratures — exactly what squeezed light and back-action evasion techniques achieve. Understanding, reaching, and then beating the SQL is the central theme of LIGO quantum optomechanics.

LIGO as a quantum optomechanical system

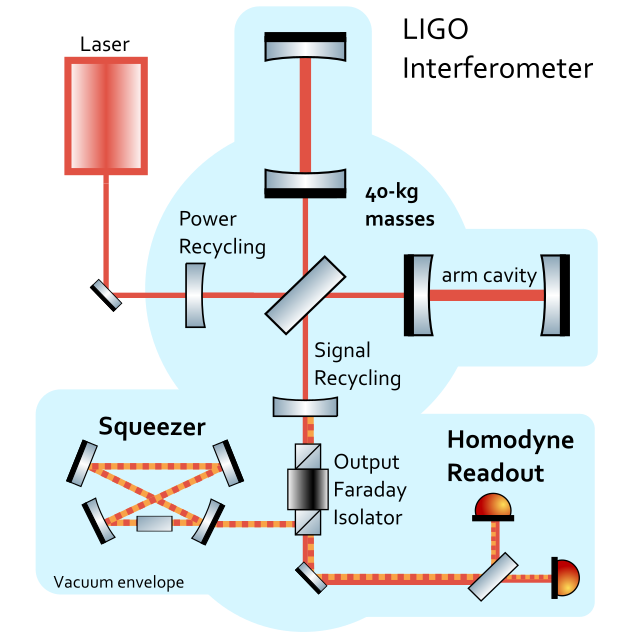

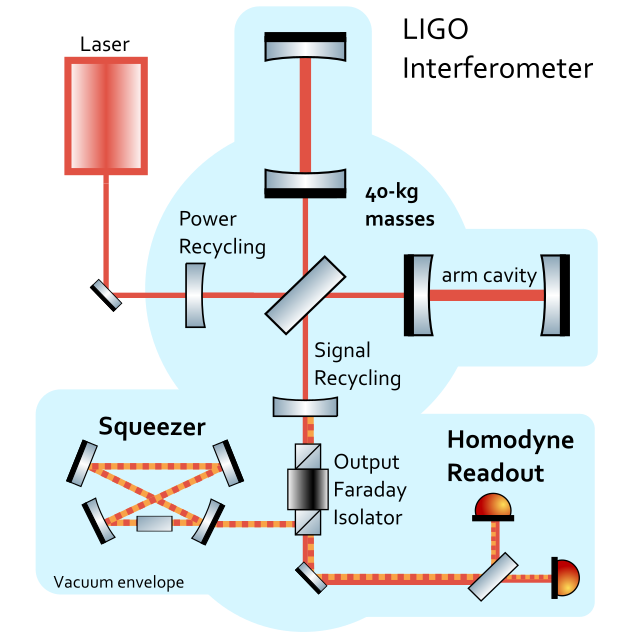

A canonical optomechanical system consists of an optical cavity with one movable mirror. The intracavity field exerts radiation pressure on the mirror; the mirror’s displacement modulates the cavity resonance, which in turn modulates the output light. This bidirectional coupling — light pushing matter, matter modulating light — is the essence of optomechanics.

LIGO implements this at an extraordinary scale. Each arm is a 4 km Fabry-Perot cavity with circulating power of ~200 kW, bouncing between 40 kg fused silica mirrors suspended as pendulums. The key dimensionless figure of merit for quantum optomechanics is the cooperativity:

\[\mathcal{C} = \frac{4g_0^2 n_\text{cav}}{\kappa \gamma_m}\]where $g_0$ is the single-photon optomechanical coupling rate, $n_\text{cav}$ is the intracavity photon number, $\kappa$ is the cavity linewidth, and $\gamma_m$ is the mechanical dissipation rate. When $\mathcal{C} \gg 1$, quantum effects dominate over thermal noise.

LIGO's optomechanical parameters

| Parameter | LIGO value | Tabletop experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Mirror mass $m$ | 40 kg | ng to mg |

| Mechanical frequency $\omega_m/2\pi$ | ~1 Hz (pendulum) | kHz to GHz |

| Mechanical quality factor $Q$ | $\sim 10^8$ (pendulum) | $10^3$ to $10^9$ |

| Cavity finesse $\mathcal{F}$ | ~450 | $10^3$ to $10^6$ |

| Circulating power $P_\text{circ}$ | ~200 kW | mW to W |

| Single-photon coupling $g_0/2\pi$ | $\sim 10^{-19}$ Hz | Hz to MHz |

| Intracavity photon number $n_\text{cav}$ | $\sim 10^{20}$ | $10^3$ to $10^{12}$ |

| Cooperativity $\mathcal{C}$ | $\gg 1$ (quantum regime) | $\sim 1$ to $\gg 1$ |

| Displacement sensitivity | $\sim 10^{-20}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ | $10^{-17}$ to $10^{-19}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ |

LIGO compensates for its minuscule $g_0$ (a consequence of massive mirrors) with an enormous intracavity photon number. The product $g_0^2 n_\text{cav}$ is large enough to place LIGO firmly in the quantum-dominated regime at audio frequencies.

Quantum correlations: the Yu et al. measurement

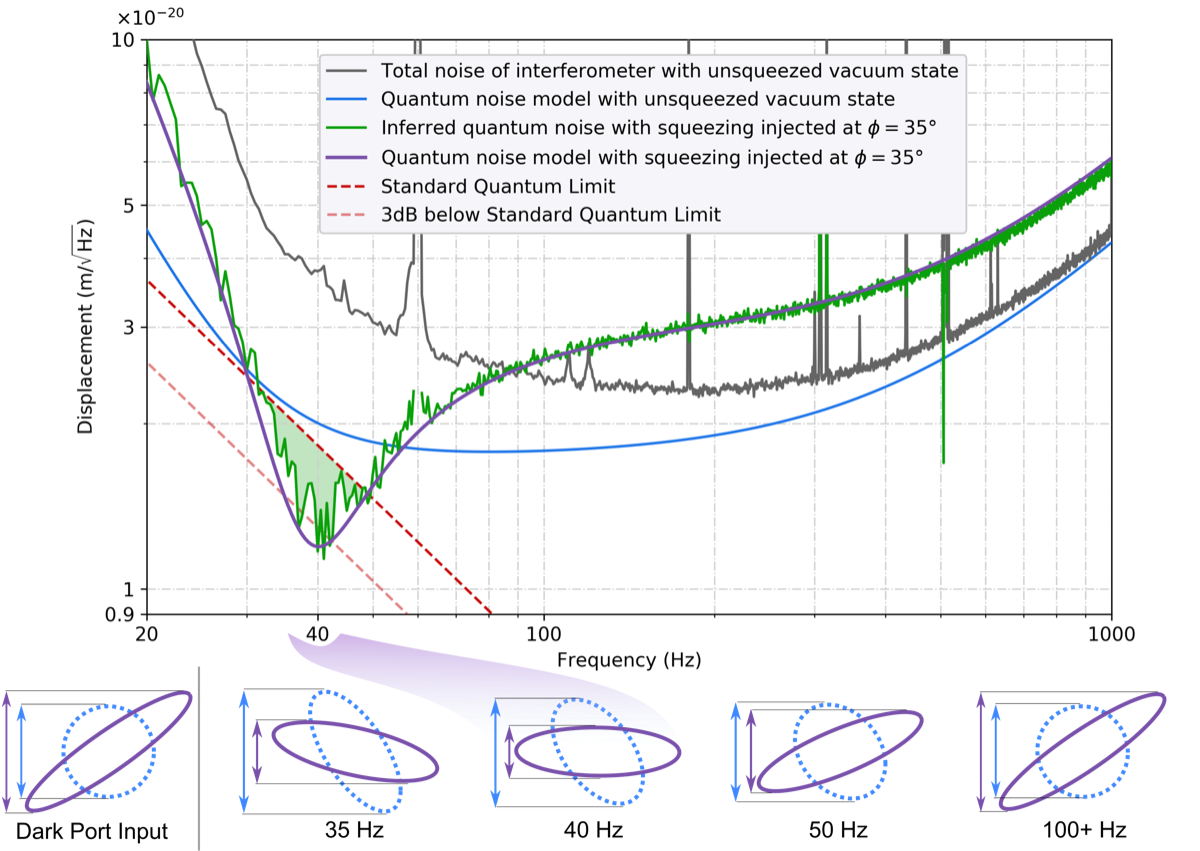

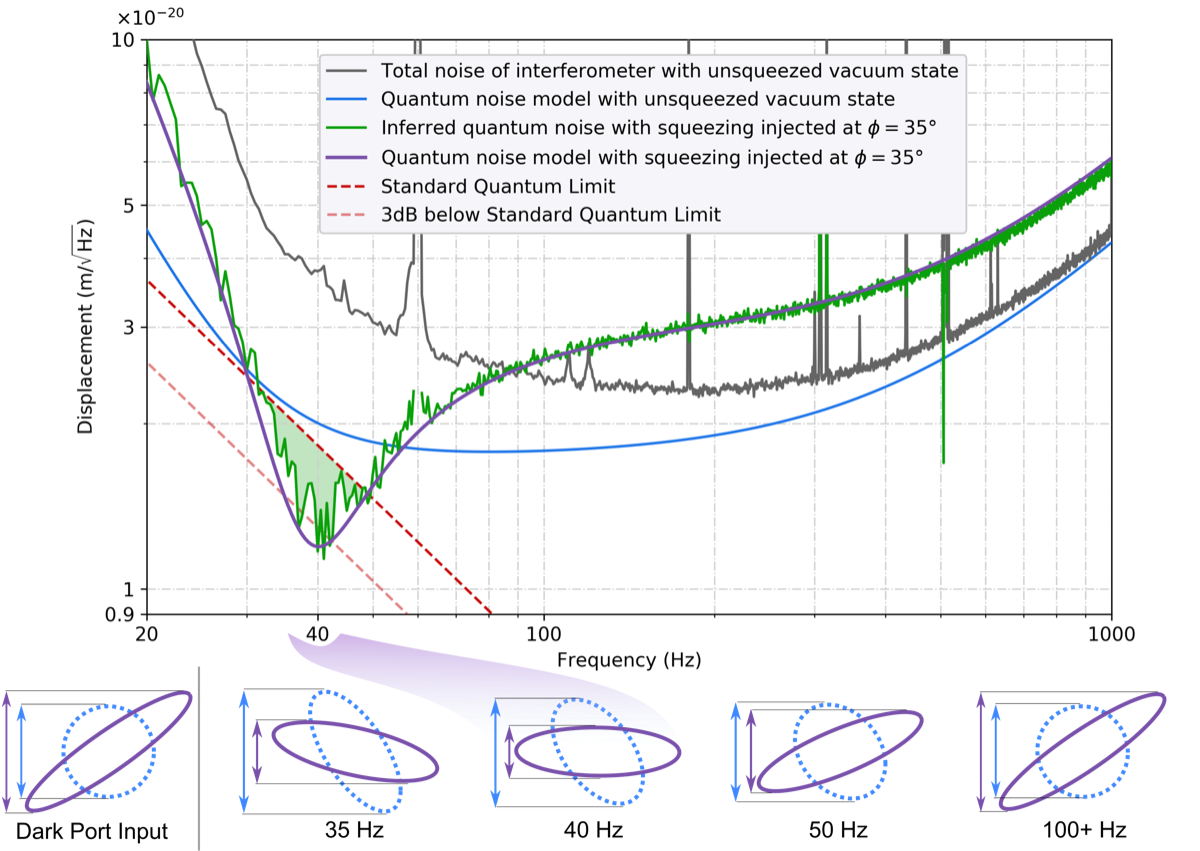

The 2020 measurement by Yu, McCuller, Tse, Barsotti, Mavalvala et al. demonstrated that quantum correlations between light and LIGO’s 40 kg mirrors are not only present but measurable — and can be exploited to beat the standard quantum limit.

The physical mechanism

When a photon reflects from a LIGO mirror, two things happen simultaneously:

- The photon transfers momentum to the mirror (radiation pressure), displacing it by $\delta x \propto \delta N / (m \omega^2)$ where $\delta N$ is the photon number fluctuation.

- The displacement modulates the phase of subsequently reflected photons: $\delta \phi \propto \delta x \propto \delta N$.

The result: the output light’s phase quadrature is correlated with its own amplitude quadrature, mediated by the mirror’s mechanical response. At frequencies where radiation pressure noise dominates (~30-60 Hz in LIGO), this correlation is strong enough to rotate the quantum noise ellipse in the amplitude-phase plane.

Measuring below the SQL

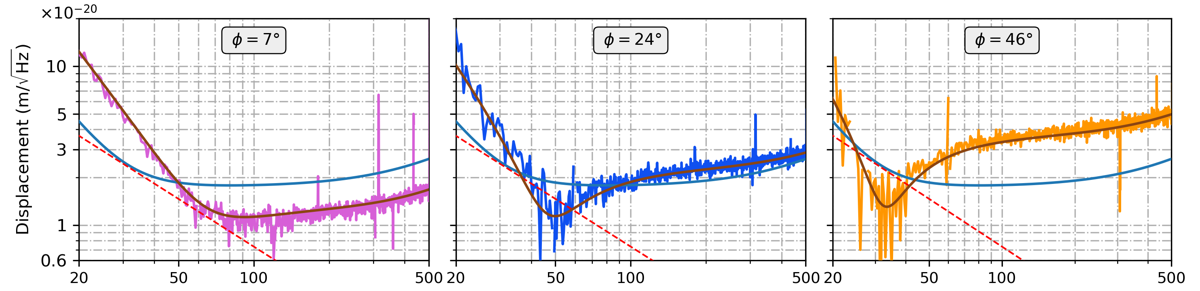

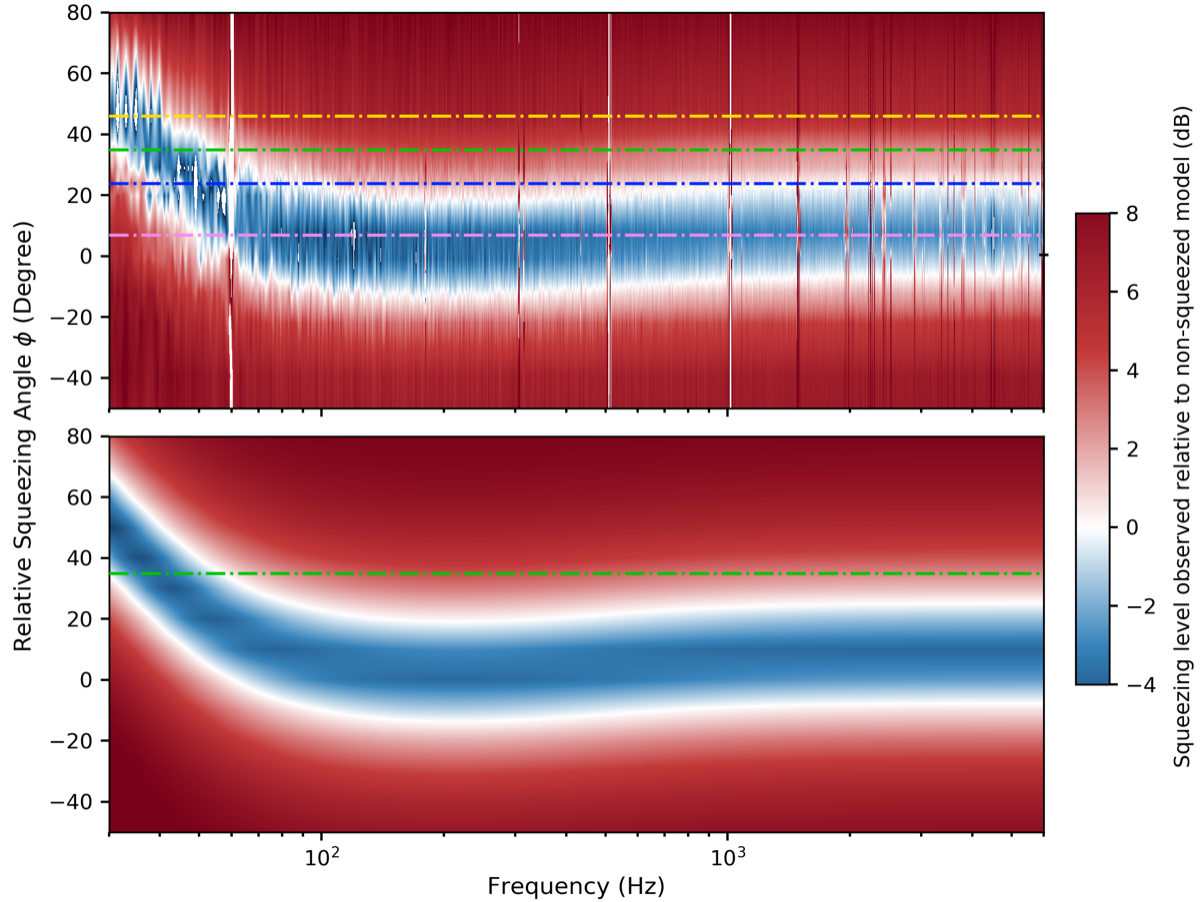

By injecting squeezed vacuum at the output port and varying the squeezing angle $\phi$, Yu et al. mapped the full structure of the quantum noise. At each frequency, there exists an optimal angle that minimizes the total noise — and at that angle, the noise drops below the SQL.

The key result: at ~40 Hz, the inferred quantum noise with optimally rotated squeezing was a factor of 1.4 (3 dB) below the standard quantum limit. This was the first demonstration of sub-SQL displacement sensitivity in a system of this mass scale.

The squeezing rotation map

The most striking visualization is the full map of observed squeezing as a function of frequency and squeezing angle. The curved boundary between noise reduction (blue) and noise enhancement (red) traces the optomechanical response of the 40 kg mirrors — a direct signature of quantum radiation pressure.

Feedback cooling to the ground state

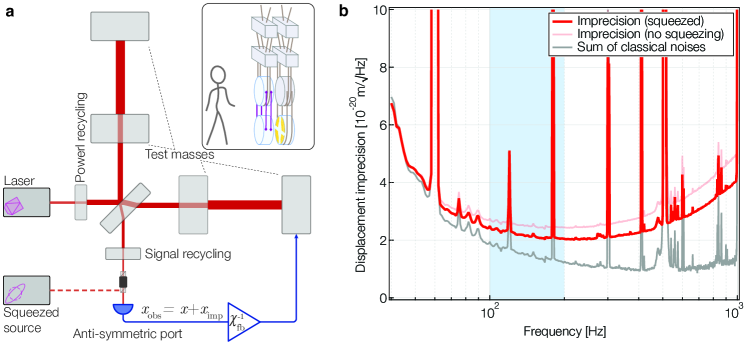

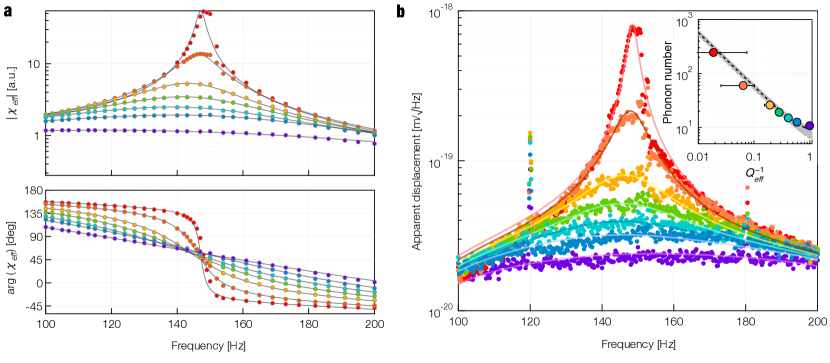

If LIGO’s mirrors are quantum optomechanical oscillators, can they be cooled to their quantum ground state? In 2021, Whittle, Hall, Dwyer, Mavalvala, Sudhir et al. demonstrated that the answer is nearly yes.

The LIGO mirrors form a 10 kg differential-mode oscillator (the two 40 kg end mirrors move antisymmetrically). At room temperature, this oscillator has a thermal occupation of approximately $n_\text{th} \sim k_B T / \hbar \omega_m \sim 10^{11}$ phonons — an astronomical number. The challenge is to remove those $10^{11}$ quanta using feedback.

The cooling scheme

The basic idea: measure the oscillator’s velocity and apply a force proportional to $-\dot{x}$ (viscous damping). LIGO’s displacement sensitivity is good enough to resolve the oscillator’s motion far below the thermal noise floor, so the feedback can extract energy faster than the thermal bath replenishes it.

The effective temperature achieved by feedback cooling is:

\[T_\text{eff} = T_\text{env} \times \frac{\gamma_m}{\gamma_m + \gamma_\text{fb}} + T_\text{meas} \times \frac{\gamma_\text{fb}}{\gamma_m + \gamma_\text{fb}}\]where $\gamma_\text{fb}$ is the feedback damping rate and $T_\text{meas}$ is the measurement noise temperature (determined by sensor noise). The first term vanishes as $\gamma_\text{fb} \gg \gamma_m$; the second is minimized by having the lowest possible measurement noise.

Quantum limits of feedback cooling

Feedback cooling cannot reach the true ground state ($\bar{n} = 0$) because the measurement itself adds noise. The fundamental limit is set by the measurement imprecision-back-action product:

\[\bar{n}_\text{min} = \sqrt{\bar{n}_\text{imp} \times \bar{n}_\text{ba}}\]where $\bar{n}\text{imp}$ is the occupation number equivalent of the measurement imprecision noise and $\bar{n}\text{ba}$ is the occupation from measurement back-action. For an SQL-limited measurement, $\bar{n}\text{imp} \times \bar{n}\text{ba} = 1/4$ (the Heisenberg limit), giving $\bar{n}_\text{min} = 1/2$.

To go below this, one needs a sub-SQL measurement — exactly what squeezing and back-action evasion provide. The quantum correlation measurement by Yu et al. is therefore not just a physics demonstration but a technology enabler for reaching deeper into the ground state.

The result

Whittle et al. cooled the 10 kg oscillator to an effective temperature of 77 nanokelvin — corresponding to a mean phonon occupation of $\bar{n} = 10.8$. This represents:

- A 13 orders-of-magnitude increase in mass over previous near-ground-state mechanical oscillators

- An 11 orders-of-magnitude suppression of quantum back-action by feedback

- A temperature reduction from ~300 K to $7.7 \times 10^{-8}$ K — a factor of $4 \times 10^{9}$

From detector to quantum laboratory

The Yu et al. and Whittle et al. results transform LIGO from a gravitational-wave observatory into a platform for fundamental quantum physics at macroscopic scales. Three research directions flow directly from this capability:

Quantum-gravity tests

Kilogram-scale masses with attometer displacement sensitivity can search for exotic noise sources predicted by models of quantum gravity:

-

Spacetime granularity: Some approaches to quantum gravity predict that spacetime has a minimum length scale (the Planck length, $\ell_P \sim 10^{-35}$ m). This would manifest as a stochastic displacement noise floor, potentially detectable by cross-correlating two co-located interferometers. The Tabletop Tests of Quantum Gravity project pursues this direction.

-

Gravitational decoherence: Penrose and Diosi independently proposed that gravity causes quantum superpositions to decohere at a rate that scales with the gravitational self-energy of the superposition: $\tau^{-1} \propto G m^2 / (\hbar R)$, where $R$ is the superposition size. For a 40 kg mirror in a superposition of two positions separated by $\Delta x$, the predicted decoherence time could be short enough to detect — if the mirror can first be prepared in a sufficiently quantum state.

-

Modified commutation relations: Some quantum gravity models modify the canonical commutation relation to $[\hat{x}, \hat{p}] = i\hbar(1 + \beta p^2 + \cdots)$, introducing a minimum measurable length. This modification changes the shape of the SQL, potentially detectable in precision measurements.

Macroscopic quantum state preparation

Preparing a 40 kg object in a genuinely quantum state — squeezed, entangled, or in a superposition — tests whether quantum mechanics holds at macroscopic scales. Any breakdown would indicate new physics: gravitational state reduction (Penrose), continuous spontaneous localization (GRW), or other decoherence mechanisms.

The path to macroscopic quantum states involves:

- Conditional squeezing: Post-selecting on measurement outcomes to prepare the mirror in a squeezed mechanical state (position uncertainty below zero-point)

- Entanglement between mirrors: Using the common light field to entangle the motions of spatially separated mirrors

- Entanglement between light and mirror: Already demonstrated implicitly by the Yu et al. quantum correlation measurement

Precision force sensing beyond gravitational waves

The same displacement sensitivity that detects gravitational waves can measure any force that moves the test masses:

- Dark matter searches: Ultralight dark matter candidates (axions, dark photons) can exert oscillatory forces on test masses at specific frequencies determined by the dark matter mass. LIGO-scale sensitivity in the 10-1000 Hz band constrains dark matter models that accelerator experiments cannot reach.

- Tests of Newtonian gravity: At short distances (~mm to cm), Yukawa-type deviations from $1/r^2$ gravity are predicted by some models with extra spatial dimensions. Precision optomechanical platforms can test these in regimes complementary to torsion balance experiments.

Why kilogram-scale? Competing platforms

Optomechanics spans an enormous range of masses and frequencies. Each platform has different strengths.

Nano- and micro-mechanical oscillators

Systems like optically levitated nanoparticles (ng), silicon nitride membranes (ng-$\mu$g), and micropillar resonators ($\mu$g) routinely achieve ground-state cooling and quantum state preparation. Their advantage: high mechanical frequencies (MHz-GHz) where thermal occupation is low and quantum control is fast. Their limitation: gravitational effects scale as $m^2$ and are immeasurably small at these masses.

Gram-scale torsion balances

Intermediate-mass systems like torsion pendulums and suspended mirror assemblies bridge the gap. They offer better gravitational coupling than nano-oscillators while remaining small enough for tabletop operation. The Tabletop Tests of Quantum Gravity project at EGG operates in this regime.

LIGO-scale (10-40 kg)

LIGO’s mirrors occupy a unique position: massive enough for gravitational effects to be significant, with displacement sensitivity already in the quantum-dominated regime. No other platform combines these two features. The disadvantage is complexity — LIGO is a 4 km facility, not a tabletop experiment. But the facility already exists, and the quantum optomechanical capability is a natural byproduct of the gravitational-wave mission.

Mass-sensitivity landscape of optomechanical platforms

| Platform | Mass | Sensitivity | Ground state? | Gravitational coupling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levitated nanoparticles | ~fg to ng | $10^{-17}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ | Yes ($\bar{n} < 1$) | Negligible |

| SiN membranes | ~ng to $\mu$g | $10^{-18}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ | Yes ($\bar{n} < 1$) | Negligible |

| Microresonators (BAW, SAW) | ~$\mu$g to mg | $10^{-19}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ | Yes ($\bar{n} \approx 0$) | Tiny |

| Torsion balances | ~g to kg | $10^{-16}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ | Not yet | Measurable |

| LIGO mirrors | 10-40 kg | $10^{-20}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$ | $\bar{n} = 10.8$ | Significant |

LIGO’s displacement sensitivity is 100-1000x better than any tabletop system, and its mass is $10^{10}$x larger than the next system that has been cooled near the ground state. This combination is why LIGO is the only platform where quantum back-action from radiation pressure has been directly observed in an interferometric measurement.

The Bose-Marletto-Vedral (BMV) proposal

A prominent class of quantum-gravity proposals (Bose et al. 2017, Marletto & Vedral 2017) seeks to demonstrate that gravity is quantum by entangling two massive objects through their gravitational interaction alone. The original proposals use $\sim\mu$g masses in Stern-Gerlach interferometers. An open question is whether LIGO-scale optomechanical systems could implement a version of this test — the gravitational coupling is much stronger, but the decoherence challenges are also much greater.

Technical challenges

Thermal noise

At frequencies where quantum effects are observable (~30-100 Hz), thermal noise from mirror coatings and suspensions competes with quantum noise. Reducing thermal noise requires either:

- Lower temperatures: Cryogenic operation at 123 K or below (as planned for LIGO Voyager)

- Better materials: Lower mechanical loss coatings (the Coating Thermal Noise project)

- Heavier mirrors: Thermal noise spectral density scales as $1/m$, favoring more massive test masses

Optical loss

Every percent of optical loss degrades squeezing and quantum correlations. Loss between the interferometer output and the photodetector converts quantum states toward vacuum, destroying the correlations needed for sub-SQL performance. Current LIGO optical losses are ~15-20%, limiting the achievable squeezing to ~4-6 dB. Reducing loss to <5% is a key goal for LIGO A# and future upgrades.

Classical noise contamination

Seismic, acoustic, and electromagnetic disturbances can mimic or mask quantum signals. LIGO’s multi-stage seismic isolation achieves attenuation factors of $>10^{10}$ above 10 Hz, but residual coupling through control system cross-talk, scattered light, and electronic noise remains a challenge — particularly at the lowest frequencies where quantum radiation pressure noise is strongest.

Bandwidth-sensitivity trade-off

The SQL decreases with frequency as $1/f^2$ (for free masses), meaning quantum effects become more prominent at lower frequencies. But classical noise sources (seismic, thermal, control noise) also increase at lower frequencies. The optimal frequency band for quantum optomechanics in LIGO is currently 30-100 Hz — a narrow window between the classical noise floor and the shot noise floor.

Connections to other EGG projects

Phase-Sensitive Optomechanical Amplifier (PSOMA)

PSOMA uses an auxiliary optomechanical cavity to amplify one quadrature of the interferometer output before photodetection, evading the loss-induced noise penalty. This is a direct application of optomechanical physics to improve the quantum performance of the readout chain — using the same radiation-pressure coupling that produces the quantum correlations measured by Yu et al., but now as a tool rather than a signal.

Quantum Control for Metrology

Non-Gaussian quantum states (photon-subtracted, Fock, cat states) can provide measurement sensitivity beyond what Gaussian squeezing achieves. Preparing and injecting these states into LIGO-scale optomechanical systems is the next frontier — requiring quantum state engineering at the intersection of quantum optics and optomechanics.

SFG Wavelength Conversion

Future detectors operating at 2 µm wavelength need high-quantum-efficiency photodetection to preserve quantum correlations and squeezing. SFG converts 2 µm photons to 700 nm where silicon detectors achieve >99% QE — maintaining the quantum coherence that enables sub-SQL operation of next-generation optomechanical platforms.

Tabletop Tests of Quantum Gravity

The quantum optomechanical capabilities demonstrated at LIGO scale motivate and inform the design of dedicated tabletop experiments targeting quantum-gravity signatures. The noise budgeting, quantum measurement techniques, and back-action management developed for LIGO directly transfer to smaller-scale platforms optimized for specific quantum-gravity tests.

Waveguide Squeezed Light Source

Optical loss is the primary barrier to deeper squeezing and stronger quantum correlations in LIGO. Integrated waveguide squeezers — producing squeezed light in lithium niobate or silicon nitride photonic circuits — could replace the current bulk-crystal optical parametric oscillators with compact, low-loss sources directly compatible with the interferometer's vacuum system, enabling the next leap in quantum optomechanical sensitivity.

Our contributions

-

Quantum correlations at kilogram scale (Yu, McCuller, Tse, Barsotti, Mavalvala et al. 2020) — First measurement of quantum correlations between light and the kilogram-mass mirrors of LIGO. Demonstrated 3 dB sub-SQL displacement sensitivity by exploiting optomechanical quantum correlations with injected squeezed light.

-

Approaching the ground state of a 10 kg oscillator (Whittle, Hall, Dwyer, Mavalvala, Sudhir et al. 2021) — Feedback-cooled LIGO’s 10 kg differential mode to 77 nanokelvin ($\bar{n} = 10.8$ phonons), extending quantum ground state preparation by 13 orders of magnitude in mass.

-

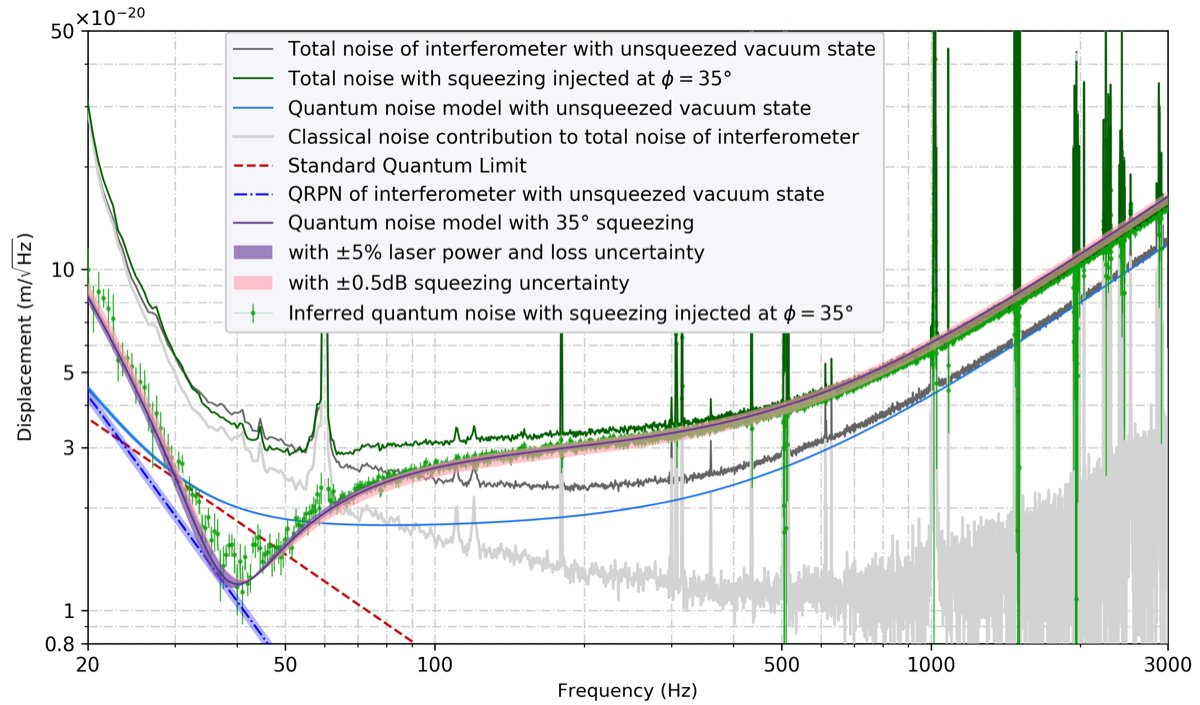

Broadband quantum enhancement with frequency-dependent squeezing (Ganapathy, Jia, Nakano et al. 2023) — Deployed 300 m filter cavities at both LIGO sites for frequency-dependent squeezing, achieving broadband quantum noise reduction from tens of Hz to several kHz — the first full realization of the Caves-Kimble-Levin-Matsko-Thorne proposal.

-

Kilogram-scale oscillator near the quantum ground state (Abbott, Abbott, Adhikari et al. 2009) — Early demonstration using Initial LIGO: cooled a 2.7 kg pendulum mode to 1.4 µK (occupation ~200 quanta) by dynamically shifting the resonance into LIGO’s optimal sensitivity band.

-

Quantum limits of interferometer topologies (Miao, Yang, Adhikari, Chen 2014) — Systematic comparison of advanced interferometer topologies for surpassing the SQL, finding that frequency-dependent squeezing with a 100 m filter cavity yields the best broadband sensitivity improvement — the design that was ultimately implemented in LIGO A+.

-

Phase-sensitive optomechanical amplifier (Bai, Venugopalan, Kuns, Wipf, Markowitz, Wade, Chen, Adhikari 2020) — Proposed using an auxiliary optomechanical device to amplify one quadrature of the interferometer output, mitigating readout losses that limit squeezed-light performance.

-

LIGO Voyager design (Adhikari, Aguiar, Arai et al. 2020) — Cryogenic silicon interferometer concept that extends optomechanical quantum capabilities to next-generation detectors with lower thermal noise and higher circulating power.

-

LIGO’s quantum response to squeezed states (McCuller, Dwyer, Green, Yu, Kuns et al. 2021) — Comprehensive characterization of how squeezed states interact with the optomechanical dynamics of km-scale interferometers, providing the physical framework for understanding quantum noise in cavity-enhanced optomechanics.

Current status and open questions

Current status: LIGO’s O4 observing run operates with frequency-dependent squeezing, routinely achieving broadband quantum noise reduction. The quantum correlation and ground-state cooling results established during O3 are being extended with the improved quantum performance of the A+ configuration. The EGG group is developing next-generation quantum measurement techniques — back-action evasion, non-Gaussian state injection, and optomechanical amplification — targeted at LIGO A# and beyond.

Open questions:

-

True ground state of a kg-scale object: Whittle et al. reached $\bar{n} = 10.8$. Can feedback cooling combined with sub-SQL measurement (squeezing, back-action evasion) reach $\bar{n} < 1$? The fundamental limit is set by measurement imprecision and optical loss — both of which are being actively reduced.

-

Verification of macroscopic quantum states: Even if a 40 kg mirror is prepared in a quantum state, how do you verify it? Standard quantum state tomography (homodyne detection of multiple quadratures) becomes extremely challenging at low frequencies where classical noise is high. What measurement protocols can distinguish a true quantum state from a very cold classical one?

-

Gravitational decoherence: Does gravity cause quantum superpositions to decohere? The Penrose-Diosi model predicts decoherence rates that could be observable for kilogram-scale objects in spatial superpositions of $\sim 10^{-15}$ m. Can optomechanical techniques prepare and verify such superpositions against overwhelming environmental decoherence?

-

Entanglement between distant mirrors: LIGO’s two arm cavities share a common laser. Can the quantum correlations between the laser and each mirror be used to entangle the two 40 kg end mirrors — producing Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) entanglement between objects separated by 4 km?

-

Optimal mass scale for quantum-gravity tests: Current platforms span ng to 40 kg. Decoherence mechanisms (thermal, optical loss, classical noise) scale differently with mass than gravitational coupling. What is the optimal mass — and is it necessarily at the LIGO scale, or could a purpose-built intermediate-mass system be more sensitive?

Key references

Foundational optomechanics

- Caves, “Quantum-mechanical noise in an interferometer,” Phys. Rev. D 23, 1693 (1981). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.23.1693 — Established the SQL for interferometric measurements and proposed squeezed light injection.

- Braginsky, Vorontsov & Thorne, “Quantum nondemolition measurements,” Science 209, 547 (1980). DOI:10.1126/science.209.4456.547 — Proposed back-action evasion to surpass the SQL.

- Kimble, Levin, Matsko, Thorne & Vyatchanin, “Conversion of conventional gravitational-wave interferometers into quantum nondemolition interferometers by modifying their input and/or output optics,” Phys. Rev. D 65, 022002 (2001). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.022002 — Proposed frequency-dependent squeezing using filter cavities.

- Aspelmeyer, Kippenberg & Marquardt, “Cavity optomechanics,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391 (2014). DOI:10.1103/RevModPhys.86.1391 — Comprehensive review of the field.

LIGO quantum measurements

- Yu, McCuller, Tse, Barsotti, Mavalvala et al., “Quantum correlations between light and the kilogram-mass mirrors of LIGO,” Nature 583, 43 (2020). DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2420-8 — Sub-SQL measurement via optomechanical quantum correlations.

- Whittle, Hall, Dwyer, Mavalvala, Sudhir et al., “Approaching the motional ground state of a 10-kg object,” Science 372, 1333 (2021). DOI:10.1126/science.abh2634 — Feedback cooling to 77 nK ($\bar{n} = 10.8$).

- Ganapathy, Jia, Nakano et al., “Broadband quantum enhancement of the LIGO detectors with frequency-dependent squeezing,” Phys. Rev. X 13, 041021 (2023). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevX.13.041021 — First frequency-dependent squeezing in full-scale GW detectors.

- McCuller, Dwyer, Green, Yu, Kuns et al., “LIGO’s quantum response to squeezed states,” Phys. Rev. D 104, 062006 (2021). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.104.062006 — Physical description of squeezing interaction with km-scale optomechanics.

Quantum-gravity proposals

- Penrose, “On gravity’s role in quantum state reduction,” Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 28, 581 (1996). DOI:10.1007/BF02105068 — Gravitational decoherence of spatial superpositions.

- Bose et al., “Spin entanglement witness for quantum gravity,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 240401 (2017). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.240401 — Gravity-mediated entanglement proposal.

- Marletto & Vedral, “Gravitationally induced entanglement between two massive particles is sufficient evidence of quantum effects in gravity,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 240402 (2017). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.240402 — Information-theoretic argument for quantumness of gravity.

EGG contributions

- Abbott, Abbott, Adhikari et al., “Observation of a kilogram-scale oscillator near its quantum ground state,” New J. Phys. 11, 073032 (2009). DOI:10.1088/1367-2630/11/7/073032

- Miao, Yang, Adhikari, Chen, “Quantum limits of interferometer topologies for gravitational radiation detection,” CQG 31, 165010 (2014). DOI:10.1088/0264-9381/31/16/165010

- Bai, Venugopalan, Kuns, Wipf, Markowitz, Wade, Chen, Adhikari, “Phase-sensitive optomechanical amplifier for quantum noise reduction in laser interferometers,” Phys. Rev. A 102, 023507 (2020). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevA.102.023507

- Adhikari, Aguiar, Arai et al., “A cryogenic silicon interferometer for gravitational-wave detection,” CQG 37, 165003 (2020). DOI:10.1088/1361-6382/ab9143

Further reading

For readers who want to go deeper:

- Danilishin & Khalili, “Quantum measurement theory in gravitational-wave detectors,” Living Rev. Relativity 15, 5 (2012). DOI:10.12942/lrr-2012-5 — Comprehensive treatment of quantum noise in interferometric GW detectors.

- Chen, “Macroscopic quantum mechanics: theory and experimental concepts of optomechanics,” J. Phys. B 46, 104001 (2013). DOI:10.1088/0953-4075/46/10/104001 — Theoretical foundations for macroscopic quantum experiments with optomechanical systems.

- Aspelmeyer, Kippenberg & Marquardt, “Cavity optomechanics,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391 (2014). DOI:10.1103/RevModPhys.86.1391 — The standard review of the field, covering theory and experiments across all mass scales.

- McCuller, “LIGO’s quantum response to squeezed states,” PhD thesis, MIT (2022). — Detailed treatment of quantum noise modeling in LIGO with squeezed light.