Precision Optical Coatings & Scattering

Characterize and improve optical coating performance — scattering, absorption, and damage threshold — for gravitational-wave detectors, fusion cavities, and precision optical systems.

Gallery

Research area

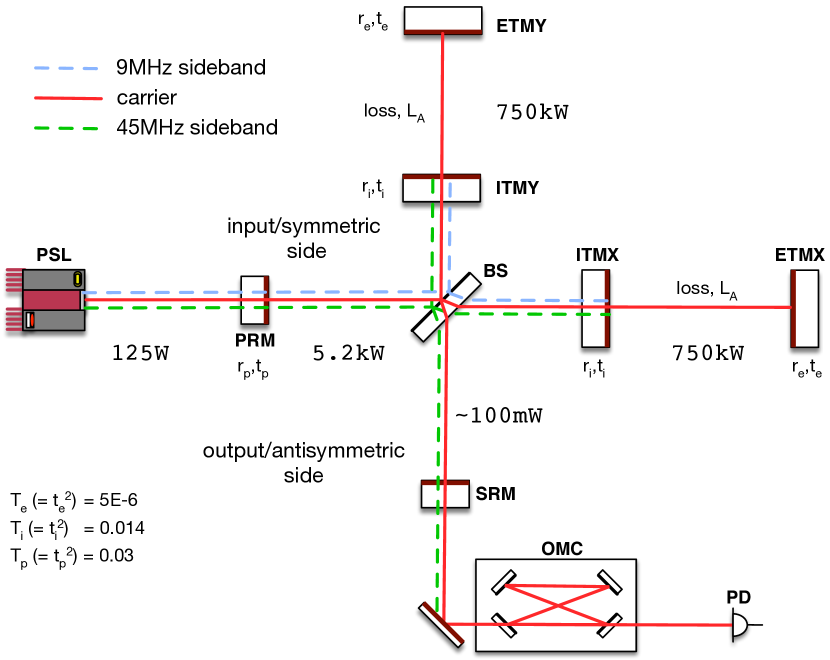

Every mirror in a gravitational-wave detector scatters and absorbs a small fraction of the light that hits it. At LIGO’s circulating powers — hundreds of kilowatts in each arm cavity — even parts-per-million losses have consequences: scattered light creates noise, absorbed light distorts the mirror, and both limit sensitivity. This project develops the measurement techniques, computational optimization tools, and fabrication science needed to push optical coating performance to the limits required by current and future detectors.

Contents:

- How coatings are made

- Scattering: where the light goes

- Point absorbers

- Measurement and characterization

- Computational coating optimization

- Stray light control: baffle coatings

- How this differs from coating thermal noise

- Competing approaches

- Connections to other fields

- Our contributions

- Current status and open questions

- Key references

- Further reading

How coatings are made

LIGO mirrors use ion-beam sputtered (IBS) dielectric coatings — alternating layers of low-index silica (SiO$_2$, $n \approx 1.45$) and high-index tantala (Ta$_2$O$_5$, $n \approx 2.06$) deposited at sub-nanometer precision. In IBS deposition, an argon ion beam sputters material from a target onto the rotating substrate inside a vacuum chamber. The process is slow — a few angstroms per second — but produces coatings with the lowest optical losses of any known technique.

A standard Advanced LIGO end test mass (ETM) coating consists of ~38 alternating layers totaling roughly 4.7 µm, achieving reflectivity >99.9995% (transmission $T < 5$ ppm). The coatings are fabricated by a handful of specialized vendors — primarily LMA Lyon (France) and CSIRO (Australia) — with each production run taking weeks.

Deposition techniques compared

| Technique | Absorption | Scatter | Uniformity | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ion beam sputtering (IBS) | <0.5 ppm | <5 ppm | ±0.1% | Slow (~Å/s) |

| Electron beam evaporation | ~10 ppm | ~50 ppm | ±1% | Fast (~nm/s) |

| Magnetron sputtering | ~5 ppm | ~20 ppm | ±0.5% | Medium |

| Atomic layer deposition | ~2 ppm | ~10 ppm | ±0.05% | Very slow |

| Crystalline bonding (AlGaAs) | <1 ppm | ~5 ppm | ±0.2% | Wafer-limited |

IBS dominates for GW detectors because it produces the amorphous films with the lowest combination of optical loss and surface roughness. The trade-off is extremely slow deposition rates and limited scalability to larger optics. For the larger mirrors planned for future detectors, uniformity across the full aperture becomes a significant engineering challenge.

The key parameters that determine coating optical performance are:

- Layer thickness accuracy — deviations from design shift the reflectivity spectrum, potentially moving the stopband away from the laser wavelength

- Surface roughness — RMS roughness below 0.1 nm is required to keep scatter below 5 ppm

- Stoichiometry — the oxygen content of the deposited oxide determines absorption, refractive index, and mechanical loss

- Contamination — metallic particles or organic residues incorporated during deposition seed point absorbers

Scattering: where the light goes

Mirror surface roughness and coating defects scatter photons out of the main beam. The scattering pattern is characterized by the bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF), which maps the scattered power per unit solid angle as a function of scatter angle. For a surface with power spectral density (PSD) of roughness $S(f_x, f_y)$, the BRDF at normal incidence is:

\[\text{BRDF}(\theta_s) = \frac{16\pi^2}{\lambda^4}\cos\theta_i\cos\theta_s \left|\Delta\varepsilon\right|^2 S(f_x, f_y)\]where $\theta_i$ and $\theta_s$ are the incidence and scatter angles, $\lambda$ is the wavelength, and $\Delta\varepsilon$ is the dielectric contrast at the scattering interface. The spatial frequency probed at scatter angle $\theta_s$ is $f = \sin\theta_s / \lambda$ — so measuring BRDF at different angles maps different spatial frequency bands of the surface roughness.

The total integrated scatter (TIS) — the fraction of incident power scattered into all angles — is related to the RMS roughness $\sigma$ by:

\[\text{TIS} = \left(\frac{4\pi\sigma}{\lambda}\right)^2\]For LIGO mirrors at 1064 nm, achieving TIS $< 5$ ppm requires $\sigma < 0.19$ nm RMS — atomically smooth surfaces.

Magaña-Sandoval, Adhikari, Frolov, Harms et al. (2012) performed the first systematic large-angle scatter measurements on superpolished optics relevant to quantum-noise filter cavities for Advanced LIGO. Their measurements at 1064 nm established the angular distribution of scattered light from IBS-coated mirrors at angles from 10° to 85° — the regime where backscatter coupling to the interferometer is strongest.

Backscatter noise coupling mechanism

Consider a photon scattered at angle $\theta$ from a cavity mirror. It travels to a vacuum chamber surface at distance $d$, reflects, and returns to the mirror. The round-trip phase accumulated is:

\[\phi = \frac{4\pi}{\lambda}\left(d + x_\text{wall}(t)\right)\]where $x_\text{wall}(t)$ is the vibration of the chamber wall. When this scattered photon recombines with the main beam, it adds a phase-modulated electric field. The resulting noise in the GW readout channel is:

\[h_\text{scatter}(f) \approx \frac{1}{L}\sqrt{\text{BRDF}(\theta) \times \Omega_\text{eff}} \times x_\text{wall}(f)\]where $L$ is the arm length and $\Omega_\text{eff}$ is the effective solid angle subtended by the scattering surface. At 10 Hz, vacuum chamber walls vibrate at levels of $\sim 10^{-10}$ m/$\sqrt{\text{Hz}}$, making scatter suppression by $>10^6$ essential to stay below the GW sensitivity floor.

Point absorbers

Point absorbers are the single biggest optical coating problem in current LIGO detectors. These are localized defects — typically 10–30 µm in diameter — embedded in the coating stack during deposition. Each absorber acts as a microscopic heat source under the high-power circulating beam, creating a local thermal bump on the mirror surface that scatters light out of the fundamental Gaussian mode.

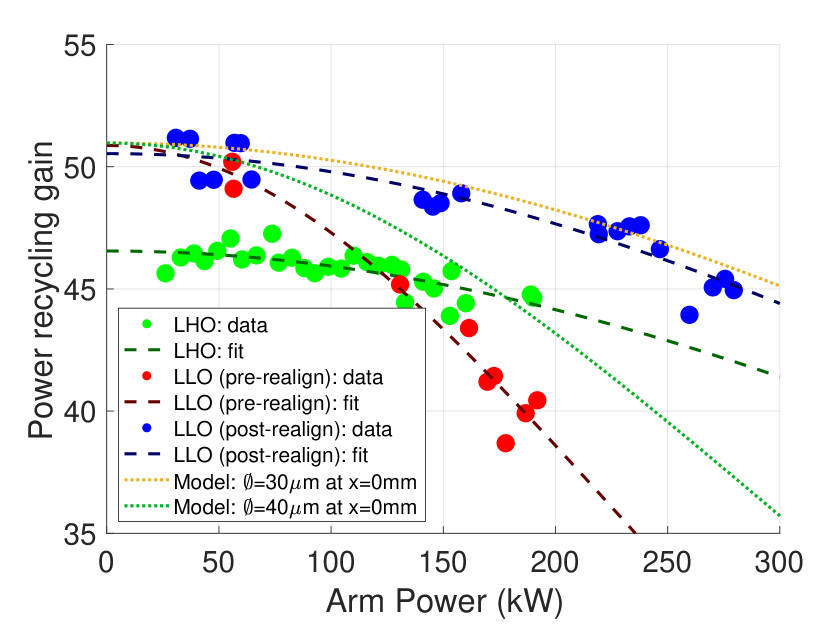

Brooks et al. (2021) provided the definitive analysis of point absorbers in Advanced LIGO. Their key findings:

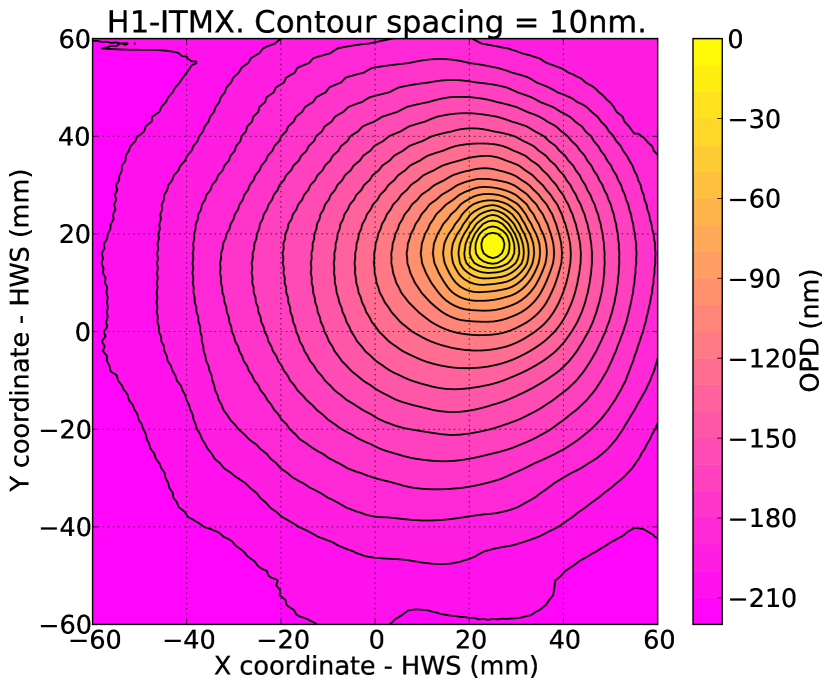

- Prevalence: Multiple point absorbers were found on each test mass, with the most problematic located on the ITMX mirror at the Hanford site (H1).

- Thermal bump amplitude: A single point absorber at 750 kW circulating power creates a thermal bump exceeding 200 nm of optical path difference — far larger than the ~1 nm surface figure specification.

- Power recycling degradation: Point absorbers reduce power recycling gain by scattering power out of the fundamental mode, effectively acting as additional round-trip loss. The measured degradation was consistent with models once the thermal bumps were included.

The physical origin of point absorbers is not fully understood. Candidates include:

- Metallic contamination from the IBS deposition chamber (sputtered particles from fixtures, chamber walls)

- Nodular growth defects seeded by particulate contamination on the substrate before coating

- Intrinsic crystallization nucleation sites in the amorphous oxide layers

- Organic contamination from handling or vacuum system outgassing

Measurement and characterization

Characterizing coatings at the ppm level requires specialized instrumentation. The EGG group and LIGO Lab use several complementary techniques:

Photothermal common-path interferometry (PCI)

A pump beam (typically 532 nm or 1064 nm) heats the coating, and a probe beam measures the resulting thermal lens through the common-path phase shift. PCI achieves sub-ppm absorption sensitivity with ~100 µm spatial resolution, enabling point-by-point mapping of the absorption across the full mirror aperture. This is the primary tool for identifying point absorbers before mirror installation.

Hartmann wavefront sensing (HWS)

Hartmann sensors measure the optical wavefront transmitted through or reflected from a test optic. By comparing wavefronts with and without the high-power beam, the thermal deformation caused by absorption can be mapped in situ — even while the interferometer is operating. The H1-ITMX thermal map shown above was measured with an in-situ HWS during LIGO operation.

Cavity ringdown

A high-finesse Fabry-Perot cavity built from the test optics measures total round-trip loss (absorption + scatter + transmission) through the decay rate of stored light after the input is switched off. For a cavity with finesse $\mathcal{F}$:

\[\tau = \frac{\mathcal{F} L}{\pi c}, \qquad \text{Total loss} = \frac{2\pi}{\mathcal{F}}\]Cavity ringdown is sensitive to total loss below 1 ppm but does not distinguish between absorption and scatter. Combining ringdown with PCI and BRDF measurements separates the loss channels.

BRDF scatterometry

A laser illuminates the optic at a defined angle, and a calibrated photodetector scans through scatter angles to map the BRDF. Multi-wavelength measurements (1064 nm, 1550 nm, 2 µm) probe different spatial frequency bands of the surface roughness, since $f_\text{spatial} = \sin\theta_s / \lambda$.

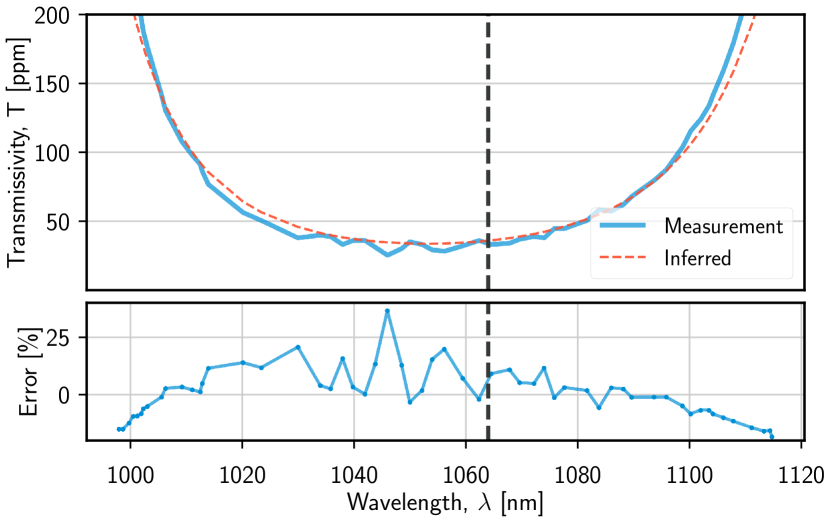

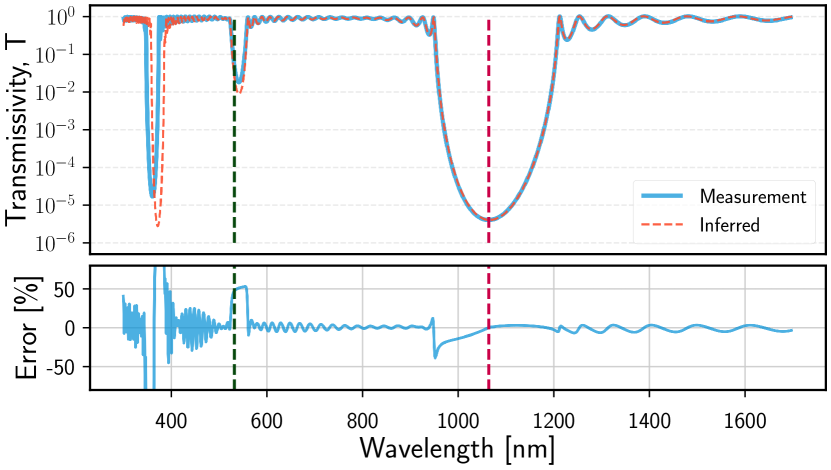

The MCMC coating diagnostic

Venugopalan, Salces-Carcoba, Arai, and Adhikari (2024) developed a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) parameter estimation technique that infers individual layer thicknesses from a broadband spectral transmissivity measurement. Given a measured transmissivity spectrum $T(\lambda)$, the algorithm explores the parameter space of all layer thicknesses simultaneously, sampling from the posterior distribution:

\[P(\{d_i\} | T_\text{meas}) \propto P(T_\text{meas} | \{d_i\}) \times P(\{d_i\})\]where ${d_i}$ are the layer thicknesses and $P({d_i})$ is a prior based on the design specification. This technique can diagnose coating fabrication errors non-destructively — identifying which layers deviate from design and by how much. It is a powerful quality control tool for both coating vendors and the LIGO collaboration.

Computational coating optimization

Designing a multilayer coating for a gravitational-wave detector is a multi-objective optimization problem. The coating must simultaneously satisfy requirements on:

- Reflectivity at the operating wavelength (e.g., $R > 99.9995\%$ for ETMs)

- Thermal noise (set by the mechanical loss angles of each layer — see the Coating Thermal Noise project)

- Absorption (depends on material choice and stoichiometry)

- Fabrication tolerance (the design must be robust to realistic layer thickness errors)

The standard quarter-wave stack (each layer $\lambda/4n$ thick) maximizes reflectivity but is not optimal for thermal noise. Hong, Yang, Gustafson, Adhikari, and Chen (2013) derived the complete theory of Brownian thermal noise in multilayer coatings, including previously neglected shear-stress-driven fluctuations at the coating-substrate interface. Their analysis showed that coating noise depends on the full strain energy distribution across the layer stack, enabling optimization of layer thicknesses away from the quarter-wave condition — at the cost of slightly reduced reflectivity.

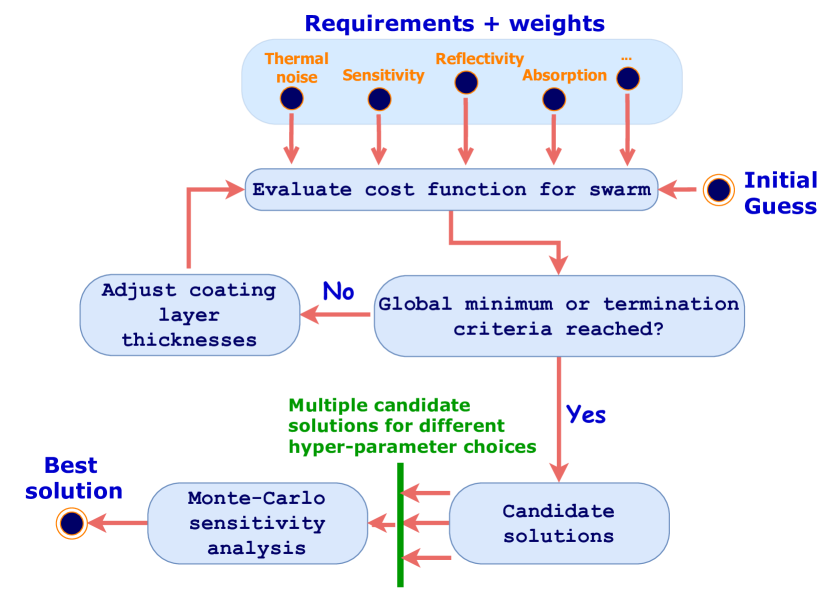

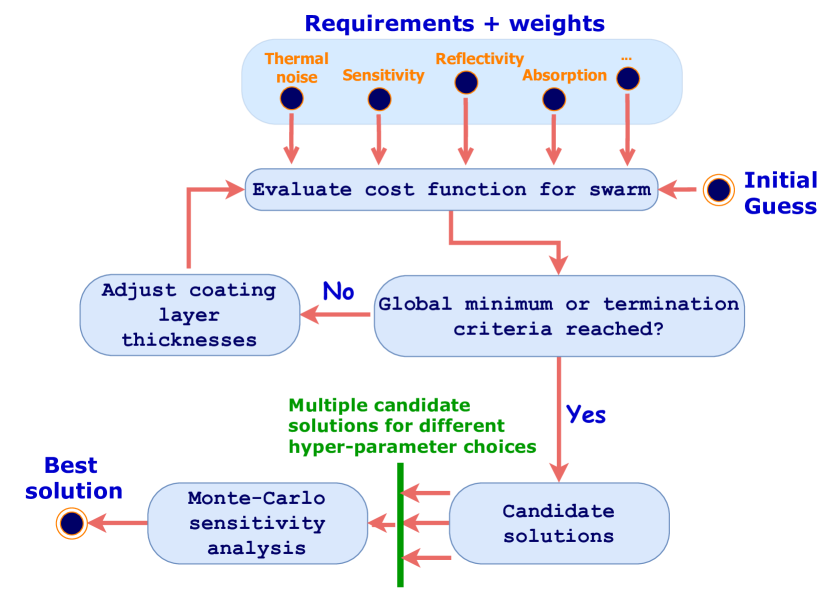

Venugopalan, Salces-Carcoba, Arai, and Adhikari (2024) developed a comprehensive global optimization framework for this problem. Their approach:

-

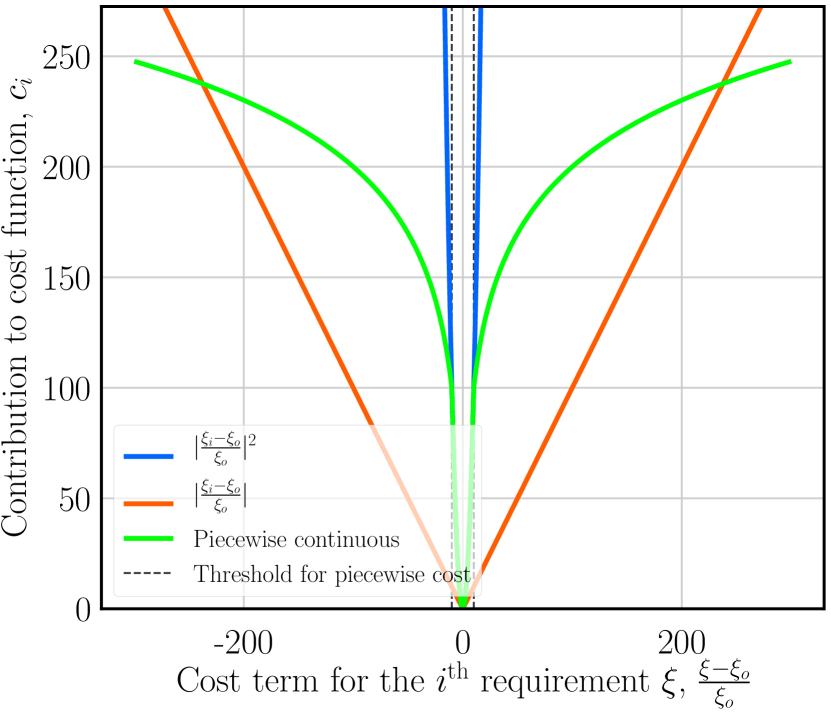

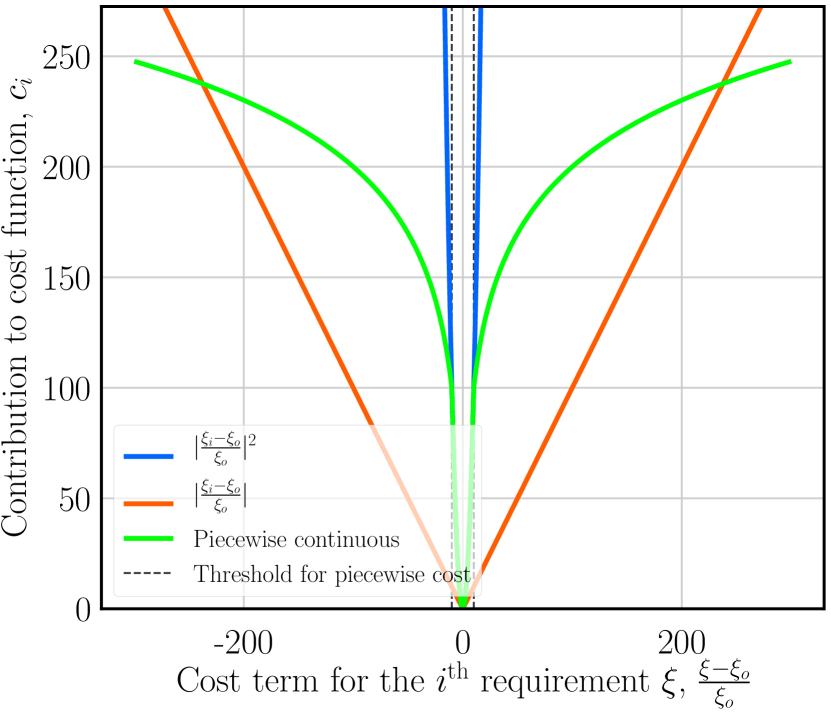

Cost function design: Each requirement (reflectivity, thermal noise, absorption, tolerance) is encoded as a term in a scalar cost function with adjustable weights. The cost function uses a piecewise-continuous penalty that is flat near the target (allowing the optimizer to explore freely) and rises steeply outside the acceptable range.

-

Global optimizer: A particle swarm optimizer explores the full parameter space — dozens of layer thicknesses simultaneously — avoiding the local minima that trap gradient-based methods.

-

Sensitivity analysis: After finding candidate optima, a Monte Carlo analysis perturbs each layer thickness within realistic fabrication tolerances to assess design robustness.

Why global optimization matters

A LIGO ETM coating has ~38 layers. If each layer thickness can vary by ±20% from the quarter-wave design, the parameter space has 38 dimensions. Gradient-based optimizers (e.g., conjugate gradient, L-BFGS) are fast but find only the nearest local minimum — and the coating design landscape is riddled with local minima.

The Venugopalan et al. (2024) approach uses particle swarm optimization (PSO), which maintains a population of candidate solutions that explore the landscape in parallel, sharing information about promising regions. PSO is derivative-free and handles the non-convex, multi-modal landscape of the coating design problem.

The result: coating designs that reduce thermal noise by up to 10% compared to the best previously known designs, while maintaining reflectivity and improving fabrication tolerance. For a 10% reduction in coating thermal noise, the corresponding improvement in GW detection range is ~3% — small but significant when integrated over years of observation.

This optimization framework is directly applicable to the Generative Optical Design project, which extends computational design to more complex optical systems.

Stray light control: baffle coatings

Not all coating challenges involve the main optics. The vacuum chambers, beam tubes, and baffles of a gravitational-wave detector must absorb stray light to prevent it from scattering back into the interferometer. An ideal baffle coating is:

- Highly absorptive across the detector’s operating wavelength (reflectivity $< 1\%$)

- Low outgassing in ultra-high vacuum ($< 10^{-8}$ Torr)

- Mechanically quiet — the coating must not add excess mechanical loss to suspended components or significantly alter their thermal noise

Two candidate technologies have been investigated by the EGG group:

Acktar Black

Acktar Black is a commercial vacuum-compatible black coating with hemispherical reflectance $< 1\%$ across 250 nm – 15 µm. Abernathy, Smith, Korth, Adhikari, Prokhorov et al. (2016) measured the mechanical loss of Acktar Black coatings applied to silicon wafers, finding that the coating adds measurable but manageable loss. This was the first systematic study of whether commercial black coatings are compatible with the mechanical performance requirements of cryogenic GW detectors.

Carbon nanotube (CNT) coatings

Vertically aligned carbon nanotube forests are among the most absorptive materials known — hemispherical reflectance $< 0.02\%$ at 1064 nm, approaching the ideal “black body” limit. Prokhorov, Mitrofanov, Kamai, Markowitz, Ni, and Adhikari (2020) measured the mechanical losses of CNT coatings on silicon wafers for use in LIGO Voyager as radiative heat extraction surfaces on the test masses.

Why baffle coating loss matters for Voyager

In LIGO Voyager, the silicon test masses are cooled to 123 K by radiating heat to cold shields. The barrel (cylindrical surface) of each test mass is coated with a high-emissivity coating to maximize radiative heat transfer. But any coating applied to the test mass contributes to its mechanical dissipation, and hence to its thermal noise.

The loss angle of the test mass sets the suspension thermal noise floor. If the barrel coating has loss angle $\phi_\text{coat}$ and covers a fraction $f$ of the test mass surface area, its contribution to the effective test mass loss is approximately:

\[\phi_\text{eff} \approx \phi_\text{bulk} + f \times \frac{t_\text{coat}}{t_\text{TM}} \times \phi_\text{coat}\]where $t_\text{coat}$ and $t_\text{TM}$ are the coating thickness and test mass thickness. Both Acktar Black and CNT coatings were measured to determine whether their mechanical loss is acceptable for this application. The CNT coatings showed loss angles of order $10^{-2}$ — high, but the coating is thin enough that its contribution to the total test mass loss budget remains manageable at cryogenic temperatures.

How this differs from coating thermal noise

The Coating Thermal Noise project focuses on the mechanical loss of coating materials — the internal friction that drives Brownian thermal displacement noise at the mirror surface. That work is about the coating’s elastic properties (loss angles, Young’s moduli, Poisson ratios) and their impact on the detector noise budget in the 50–300 Hz band.

This project focuses on the optical properties of coatings — scattering, absorption, damage threshold, point defects, and environmental degradation — and the computational tools to optimize coating designs across multiple objectives simultaneously. The materials science overlaps significantly (both projects deal with amorphous oxide thin films deposited by IBS), but the measurement techniques, failure modes, and design trade-offs are distinct.

The connection: A coating with low mechanical loss but high scatter would still limit detector performance. And a coating optimized for low scatter but high mechanical loss would be noise-limited by thermal fluctuations. The two projects are complementary halves of the same problem: making mirrors that are both mechanically quiet and optically perfect.

Competing approaches

Direct-bonded crystalline coatings (AlGaAs)

Epitaxially grown GaAs/AlGaAs multilayers — single-crystalline rather than amorphous — offer dramatically lower mechanical loss ($\phi \sim 10^{-5}$, roughly 40× better than tantala). Their optical properties are also excellent: scatter below 5 ppm and absorption below 1 ppm at 1064 nm. But several challenges remain for GW applications: the coatings are grown on GaAs wafers and must be bonded to silica or silicon substrates, limiting the maximum diameter to ~20 cm (current wafer sizes). Birefringence from the crystalline structure requires careful orientation of the coating axes relative to the cavity polarization. The Coating Thermal Noise page discusses the mechanical loss advantages in detail.

Multi-material amorphous coatings

Instead of the standard SiO$_2$/Ta$_2$O$_5$ bilayer, alternative amorphous materials — titania-doped tantala (TiO$_2$:Ta$_2$O$_5$), amorphous silicon (a-Si), silicon nitride (SiN$_x$), hafnia (HfO$_2$) — offer different trade-offs between refractive index, mechanical loss, and optical absorption. The computational optimization framework of Venugopalan et al. (2024) is material-agnostic and can explore these trade-offs systematically, searching for layer structures that exploit the best properties of multiple materials.

Annealing and post-processing

Post-deposition annealing at 400–600 °C reduces both mechanical loss and optical absorption in IBS coatings by relaxing the amorphous structure and healing point defects. However, the optimal annealing temperature depends on the material system — tantala crystallizes above ~600 °C, destroying the amorphous structure. Controlled annealing protocols can reduce absorption by factors of 2–5× while maintaining amorphous character.

Improved deposition techniques

Modifications to the IBS process — plasma-assisted deposition, reactive sputtering with controlled oxygen partial pressure, substrate temperature control during deposition — can improve stoichiometry and reduce defect density. Ion-assisted deposition adds a secondary ion beam that bombards the growing film, increasing density and reducing porosity. These process improvements are incremental but cumulative: the best modern IBS coatings achieve 2–3× lower absorption than those made a decade ago.

Connections to other fields

Laser frequency stabilization

High-finesse Fabry-Perot reference cavities used for laser frequency stabilization require mirror coatings with total loss below 3 ppm to achieve finesses above 500,000. The same IBS coating technology, characterization techniques, and optimization tools developed for GW detectors directly serve the precision metrology community — including optical clocks, cavity QED experiments, and tests of fundamental physics. The coating thermal noise work is equally relevant, as reference cavity stability is often limited by mirror coating Brownian noise.

High-power laser systems

The fusion cavity project needs mirrors that withstand MW-level circulating power without damage or degradation. At MW/cm² intensities, even 0.1 ppm absorption creates thermal runaway — the absorbed power heats the coating, increasing absorption (through temperature-dependent material properties), which heats the coating further. Understanding and minimizing point absorbers is critical for these extreme applications.

Multi-band optical coatings

The SFG cavity for LIGO Voyager readout requires low-loss coatings at multiple wavelengths simultaneously (1064 nm, 2050 nm, and 700 nm) — a challenging multi-band design problem where the layer structure must be optimized for reflectivity at three wavelengths while maintaining low loss at all three. The global optimization framework of Venugopalan et al. (2024) is directly applicable to this problem.

Space optics and remote sensing

Space-based gravitational-wave detectors (LISA), Earth observation satellites, and astronomical telescopes all require optical coatings with exceptional scatter and absorption performance that must survive the space environment — radiation exposure, thermal cycling, and atomic oxygen bombardment. The measurement and characterization techniques developed for LIGO coatings serve as the gold standard for qualifying space optics.

Coatings for 2 µm wavelength

LIGO Voyager will operate at 2 µm on crystalline silicon substrates. The standard SiO₂/Ta₂O₅ stack must be redesigned — alternative materials (amorphous silicon, germanium compounds) have different scatter and absorption properties at this wavelength. The full characterization infrastructure (BRDF, PCI, ringdown) must be rebuilt at 2 µm, and the computational optimization tools extended to new material systems.

Our contributions

-

Global coating optimization (Venugopalan, Salces-Carcoba, Arai, and Adhikari 2024) — Developed a comprehensive framework for optimizing multilayer dielectric coatings using particle swarm global optimization and MCMC layer thickness inference. The optimizer simultaneously targets reflectivity, thermal noise, absorption, and fabrication tolerance. The MCMC diagnostic tool can non-destructively infer individual layer thicknesses from a broadband transmissivity measurement — a powerful quality control capability for coating vendors and the LIGO collaboration.

-

Coating thermal noise theory (Hong, Yang, Gustafson, Adhikari, and Chen 2013) — Derived the complete theory of Brownian thermal noise in multilayer coatings, including the previously neglected contributions from shear-stress-driven fluctuations at the coating-substrate interface. This work provides the thermal noise cost function used in the optimization framework above, connecting mechanical loss measurements to detector noise performance.

-

Broadband coating thermal noise measurement (Chalermsongsak, Seifert, Hall, Arai, Gustafson, and Adhikari 2015) — Measured the length fluctuation of two rigid Fabry-Perot cavities from 10 Hz to 1 kHz, achieving direct broadband measurement of coating thermal noise consistent with the fluctuation-dissipation theorem. This validated the Hong et al. theory and established the measurement technique for characterizing new coating materials.

-

Large-angle scatter measurements (Magaña-Sandoval, Adhikari, Frolov, Harms et al. 2012) — First systematic BRDF measurements at large scatter angles on superpolished optics for quantum-noise filter cavity design. These measurements established the angular distribution of scattered light that determines backscatter noise coupling in advanced interferometer configurations.

-

Acktar Black mechanical loss (Abernathy, Smith, Korth, Adhikari, Prokhorov et al. 2016) — Measured the mechanical loss of Acktar Black coatings on silicon wafers, determining whether this commercial vacuum-compatible absorber is suitable for stray-light control in cryogenic GW detectors.

-

CNT coating mechanical loss (Prokhorov, Mitrofanov, Kamai, Markowitz, Ni, and Adhikari 2020) — Measured mechanical losses of carbon nanotube coatings on silicon wafers for LIGO Voyager, establishing their suitability as high-emissivity radiative heat extraction surfaces on cryogenic test masses.

Current status and open questions

Current status: The coating optimization framework (Venugopalan et al. 2024) is actively being applied to design coatings for Advanced LIGO+, LIGO Voyager, and future large-aperture detectors. The MCMC diagnostic tool is being used for quality control of production coatings. Point absorber characterization continues at both LIGO sites using photothermal imaging and Hartmann wavefront sensing.

Open questions:

-

Point absorber mitigation: Can improved IBS deposition techniques — plasma cleaning of substrates, better chamber vacuum, optimized deposition angles — reduce point absorber density to acceptable levels for A+ and future detectors? Or is a fundamentally different coating technology needed? The root cause of point absorbers remains an active area of investigation.

-

Coatings at 2 µm: LIGO Voyager requires a complete coating development program at 2 µm: new material systems (amorphous silicon is promising but has high absorption without careful hydrogenation), new characterization infrastructure, and optimization for a silicon substrate instead of fused silica.

-

Environmental degradation: LIGO mirrors operate in ultra-high vacuum for years. Monitoring data from Advanced LIGO shows that some coatings degrade over time — scatter increases, new point absorbers appear. Is this due to residual gas adsorption, radiation damage from the high-power laser, or mechanical stress evolution in the coating stack? Long-term degradation data is essential for planning detector upgrades.

-

Large-aperture uniformity: Future detectors will require mirrors significantly larger than LIGO’s 34 cm optics. Maintaining sub-ppm absorption and sub-nm roughness uniformity across a larger aperture pushes IBS deposition technology to its limits. Alternative approaches (dual-ion-beam co-sputtering, planetary rotation fixtures) are being explored.

-

Multi-objective optimization at scale: Current optimization handles ~40 layers with ~5 objectives. Future coatings may use 3+ materials, 60+ layers, and 10+ objectives (including thermal conductivity, optical path length sensitivity to temperature, and stress balancing). Extending the global optimization framework to these higher-dimensional problems requires algorithmic advances.

Key references

Coating fabrication and characterization

- Rempe et al., “Measurement of ultralow losses in an optical interferometer,” Opt. Lett. 17, 363 (1992). DOI:10.1364/OL.17.000363 — Demonstrated sub-ppm cavity losses, establishing the baseline for modern IBS coatings.

- Stover, Optical Scattering: Measurement and Analysis, 3rd ed. (SPIE Press, 2012). — The standard reference for BRDF measurement and surface scatter theory.

- Alexandrovski et al., “Photothermal common-path interferometry (PCI): new developments,” Proc. SPIE 7193, 71930D (2009). DOI:10.1117/12.814813 — The PCI technique used for ppm-level absorption mapping.

Point absorbers and scatter

- Brooks et al., “Point absorbers in Advanced LIGO,” Appl. Opt. 60, 4047 (2021). arXiv:2101.05828 — Definitive analysis of point absorber impact on LIGO performance.

- Magaña-Sandoval, Adhikari et al., “Large-angle scattered light measurements for quantum-noise filter cavity design studies,” JOSA A 29, 1722 (2012). DOI:10.1364/josaa.29.001722

- Ottaway et al., “In situ measurement of absorption in high-power interferometers by using beam diameter measurements,” Opt. Lett. 31, 450 (2006). DOI:10.1364/OL.31.000450 — In-situ absorption measurement technique.

Coating optimization

- Venugopalan, Salces-Carcoba, Arai, and Adhikari, “Global optimization of multilayer dielectric coatings for precision measurements,” Opt. Express 32 (2024). DOI:10.1364/oe.513807 — Global optimization + MCMC diagnostics framework.

- Hong, Yang, Gustafson, Adhikari, and Chen, “Brownian thermal noise in multilayer coated mirrors,” Phys. Rev. D 87, 082001 (2013). DOI:10.1103/physrevd.87.082001 — Thermal noise theory for optimized coatings.

Coating thermal noise measurement

- Chalermsongsak, Seifert, Hall, Arai, Gustafson, and Adhikari, “Broadband measurement of coating thermal noise in rigid Fabry-Perot cavities,” Metrologia 52, 17 (2015). DOI:10.1088/0026-1394/52/1/17

- Numata et al., “Thermal-noise limit in the frequency stabilization of lasers with rigid cavities,” PRL 93, 250602 (2004). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.250602 — First direct observation of coating thermal noise in a reference cavity.

Baffle and absorber coatings

- Abernathy, Smith, Korth, Adhikari et al., “Measurement of mechanical loss in the Acktar Black coating of silicon wafers,” CQG 33, 185002 (2016). DOI:10.1088/0264-9381/33/18/185002

- Prokhorov, Mitrofanov, Kamai, Markowitz, Ni, and Adhikari, “Measurement of mechanical losses in the carbon nanotube black coating of silicon wafers,” CQG 37, 025009 (2020). DOI:10.1088/1361-6382/ab5357

GW detector context

- Adhikari et al., “A cryogenic silicon interferometer for gravitational-wave detection,” CQG 37, 165003 (2020). DOI:10.1088/1361-6382/ab9143 — LIGO Voyager design establishing requirements for next-generation coatings.

Further reading

For readers who want to go deeper:

- Macleod, Thin-Film Optical Filters, 5th ed. (CRC Press, 2017) — the standard textbook for multilayer coating design, covering thin-film optics theory, deposition methods, and characterization.

- Stover, Optical Scattering: Measurement and Analysis, 3rd ed. (SPIE Press, 2012) — comprehensive treatment of surface scatter theory, BRDF measurement, and roughness-scatter relationships.

- Harry et al., “Titania-doped tantala/silica coatings for gravitational-wave detection,” CQG 24, 405 (2007). DOI:10.1088/0264-9381/24/2/008 — First demonstration of doped tantala reducing mechanical loss for GW coatings.

- Granata et al., “Progress in the measurement and reduction of thermal noise in optical coatings for gravitational-wave detectors,” Appl. Opt. 59, A229 (2020). DOI:10.1364/AO.377293 — Comprehensive review of the GW coating program.

- Penn et al., “Mechanical loss in tantala/silica dielectric mirror coatings,” CQG 20, 2917 (2003). DOI:10.1088/0264-9381/20/13/334 — Early measurement connecting coating mechanical loss to thermal noise.

Related publications

-

Global optimization of multilayer dielectric coatings for precision measurements

-

Brownian thermal noise in multilayer coated mirrors

-

Broadband measurement of coating thermal noise in rigid Fabry–Pérot cavities

-

Large-angle scattered light measurements for quantum-noise filter cavity design studies

-

Measurement of mechanical losses in the carbon nanotube black coating of silicon wafers

-

Measurement of mechanical loss in the Acktar Black coating of silicon wafers