LIGO Voyager

Design and prototype cryogenic silicon interferometer technology for the next major LIGO upgrade — 200 kg silicon test masses at 123 K with 2 µm laser light, targeting 5× sensitivity improvement and 125× event rate.

Gallery

Research area

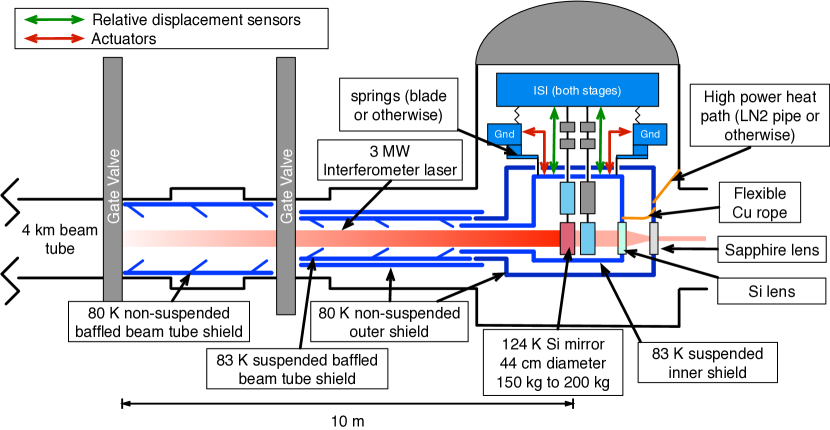

LIGO Voyager is the planned next major upgrade to the LIGO detectors — a cryogenic silicon interferometer that would replace nearly every optical component inside the existing 4 km vacuum infrastructure. Where Advanced LIGO uses room-temperature fused silica mirrors and 1064 nm laser light, Voyager would use 200 kg silicon test masses cooled to 123 K and illuminated at wavelengths between 1550 and 2050 nm. The result is a qualitatively different instrument built inside the same buildings and vacuum system, targeting a factor of ~5 improvement in broadband strain sensitivity over Advanced LIGO.

Contents:

- Why cryogenic silicon?

- The Voyager noise budget

- Silicon at 123 K

- Radiative cooling and thermal management

- Laser and photodetection at 2 µm

- Coatings for Voyager

- Parametric instabilities

- Related programs: ET, ET Pathfinder, and KAGRA

- Connections to other fields

- Our contributions

- Key references

Why cryogenic silicon?

Advanced LIGO’s sensitivity in the 50–300 Hz band — the most astrophysically important frequency range for compact binary coalescences — is limited by coating thermal noise. The thin dielectric coatings on each mirror (alternating layers of tantala and silica, totaling ~5 µm) have internal mechanical loss angles of order \(\phi \sim 4 \times 10^{-4}\), and through the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, this loss produces Brownian displacement noise that sets the sensitivity floor.

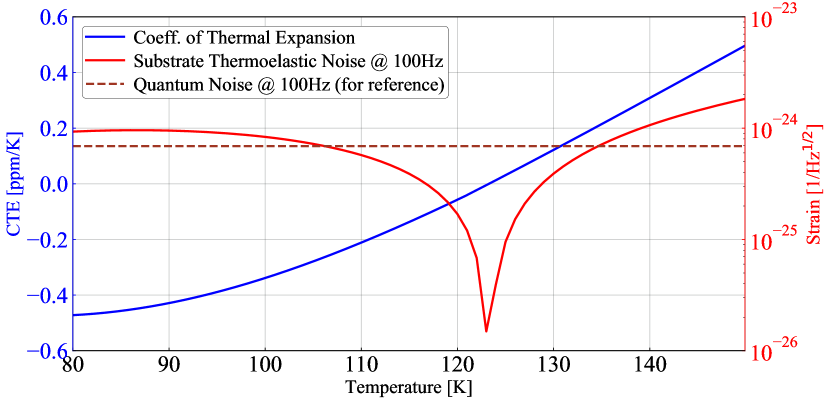

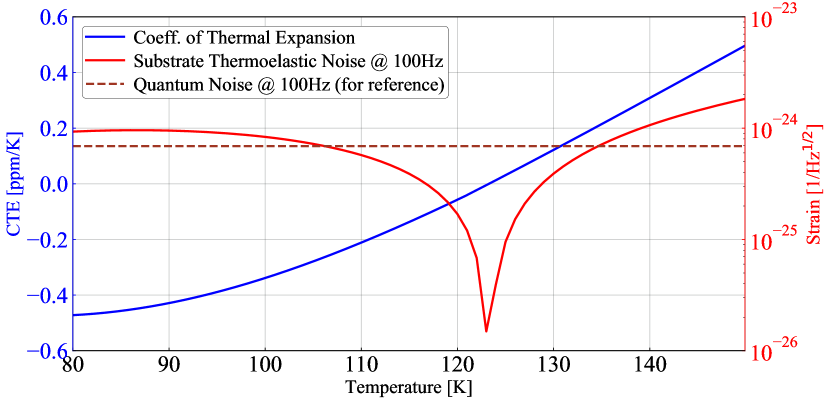

There are two routes to reducing thermal noise: improve the coatings, or cool the mirrors. LIGO’s A+ upgrade pursues the first strategy, but fused silica becomes mechanically lossy at low temperatures — its internal friction rises below ~150 K due to thermally activated relaxation processes. Silicon, by contrast, has excellent cryogenic properties: its mechanical quality factor \(Q\) exceeds \(10^8\) at 123 K, and at that same temperature its coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) passes through zero, suppressing thermoelastic noise.

Changing the substrate from fused silica to silicon has cascading consequences. Silicon is opaque at 1064 nm, so the laser wavelength must change to 1550 nm or 2050 nm, where silicon is transparent. New wavelengths require new laser sources, new photodetectors, new optical coatings, and new squeezed light sources. The test masses must be suspended and cooled without mechanical contact. The entire thermal management system — heat deposition from absorbed laser light, radiative coupling to the cryogenic environment — must be redesigned. Voyager is, in effect, a new instrument inside existing infrastructure.

Fused silica vs silicon: material properties comparison

| Property | Fused silica (300 K) | Silicon (123 K) |

|---|---|---|

| Young's modulus | 72 GPa | 164 GPa |

| Mechanical Q | ~10⁷ | >10⁸ |

| CTE | 5.5 × 10⁻⁷ /K | ~0 (zero-crossing) |

| Thermal conductivity | 1.4 W/m·K | ~700 W/m·K |

| Density | 2.2 g/cm³ | 2.3 g/cm³ |

| Optical absorption (1064 nm) | <1 ppm/cm | Opaque |

| Optical absorption (2 µm) | — | <0.1 ppm/cm (expected) |

Silicon's thermal conductivity at 123 K is roughly 500× that of fused silica at room temperature, which helps distribute absorbed laser power uniformly across the test mass. The high Young's modulus raises acoustic mode frequencies, affecting parametric instability calculations.

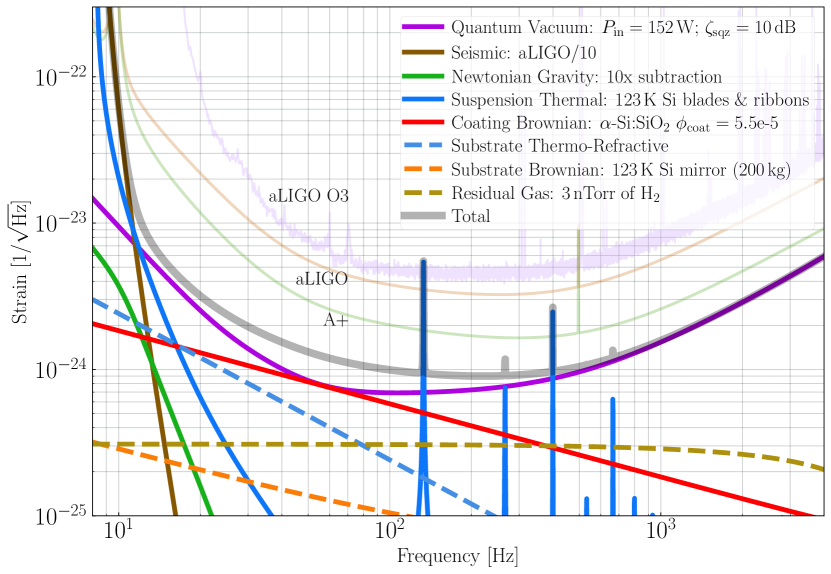

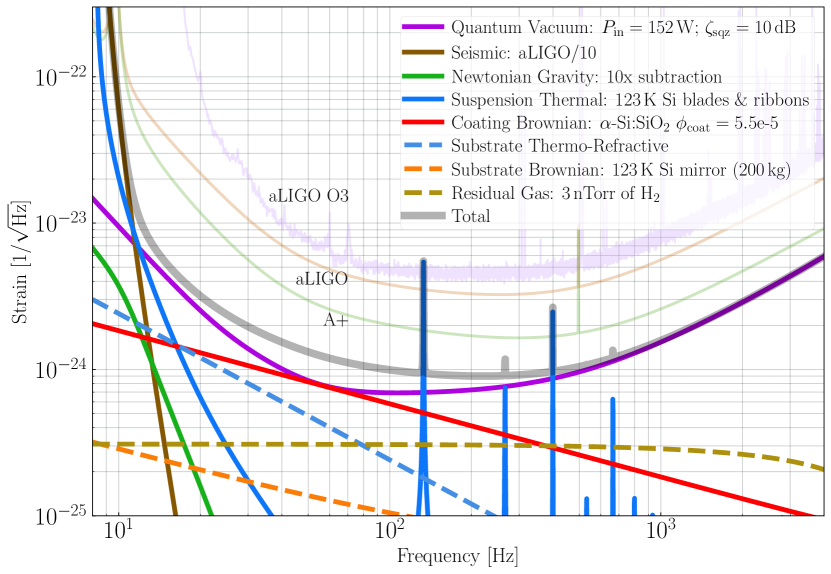

The Voyager noise budget

The Voyager reference design (Adhikari et al. 2020) targets a broadband sensitivity roughly 5× better than Advanced LIGO. The noise budget includes:

Quantum noise dominates at both low frequencies (radiation pressure) and high frequencies (shot noise). Voyager’s design calls for ~2 MW of circulating power in each arm cavity and 10 dB of frequency-dependent squeezed light injected through a 300 m filter cavity — the same architecture being demonstrated by LIGO A+.

Coating thermal noise is reduced by cooling to 123 K, using silicon substrates with higher mechanical quality, and employing coating materials with lower loss at cryogenic temperatures. The target coating loss is \(\phi_c \lesssim 1 \times 10^{-4}\) — roughly 4× better than current Advanced LIGO coatings.

Suspension thermal noise benefits from silicon’s high mechanical Q. The last stage of the quadruple pendulum suspension would use silicon ribbons or fibers bonded to the test mass, replacing the current fused silica fibers.

Newtonian noise — fluctuations in the local gravitational field from seismic surface waves — becomes significant below ~20 Hz. Driggers, Harms, and Adhikari (2012) developed optimized sensor array methods for subtracting this noise using surface seismometer arrays surrounding each test mass.

Key design parameters:

- Test mass: 200 kg crystalline silicon, 45 cm diameter

- Arm length: 4 km (existing LIGO infrastructure)

- Laser wavelength: 2050 nm (baseline) or 1550 nm (alternative)

- Circulating arm power: ~2 MW

- Test mass temperature: 123 K

- Squeezing: 10 dB frequency-dependent via 300 m filter cavity

Silicon at 123 K

The choice of 123 K is not arbitrary — it is the temperature at which silicon’s thermal expansion coefficient passes through zero. At this zero-crossing, thermoelastic noise (driven by temperature fluctuations coupling to dimensional changes via the CTE) vanishes to leading order. The thermoelastic noise spectral density scales as \(\alpha^2\), where \(\alpha\) is the CTE, so operating at \(\alpha = 0\) eliminates this entire noise mechanism. (Silicon has a second zero-crossing near 18 K, but the higher temperature is preferred for practical cooling reasons.)

Beyond the CTE advantage, silicon at 123 K has:

- High mechanical Q: Intrinsic quality factors exceeding \(10^8\) in bulk silicon at 123 K, compared to ~\(10^7\) for fused silica at room temperature. Higher Q means lower Brownian noise for the substrate contribution.

- High thermal conductivity: ~700 W/m·K at 123 K (vs 1.4 W/m·K for fused silica at 300 K). This means absorbed laser power is efficiently conducted through the test mass rather than creating localized hot spots.

- Low optical absorption: At 2 µm wavelength, high-resistivity float-zone silicon has optical absorption below 0.1 ppm/cm — comparable to or better than fused silica at 1064 nm.

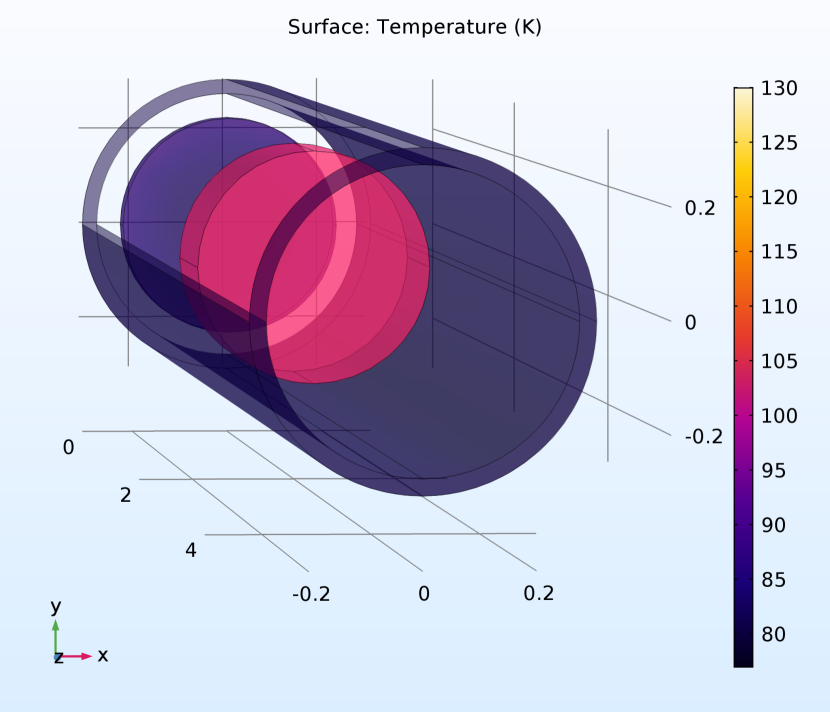

Constancio et al. (2020) measured the total hemispherical emissivity of silicon as a function of temperature from 100 K to 300 K. This measurement is critical for radiative cooling design: it determines how efficiently the test mass can radiate away absorbed laser power. They found that bulk silicon may have sufficient emissivity for moderate absorbed power levels, potentially eliminating the need for high-emissivity coatings on the optical surfaces.

Klochkov et al. (2022) used silicon disk resonators to measure mechanical losses induced by electric fields — directly relevant to Voyager because electrostatic actuators (used for test mass alignment and control) can introduce additional loss. Their measurements constrain the allowable field strengths and actuator geometries for the Voyager control system.

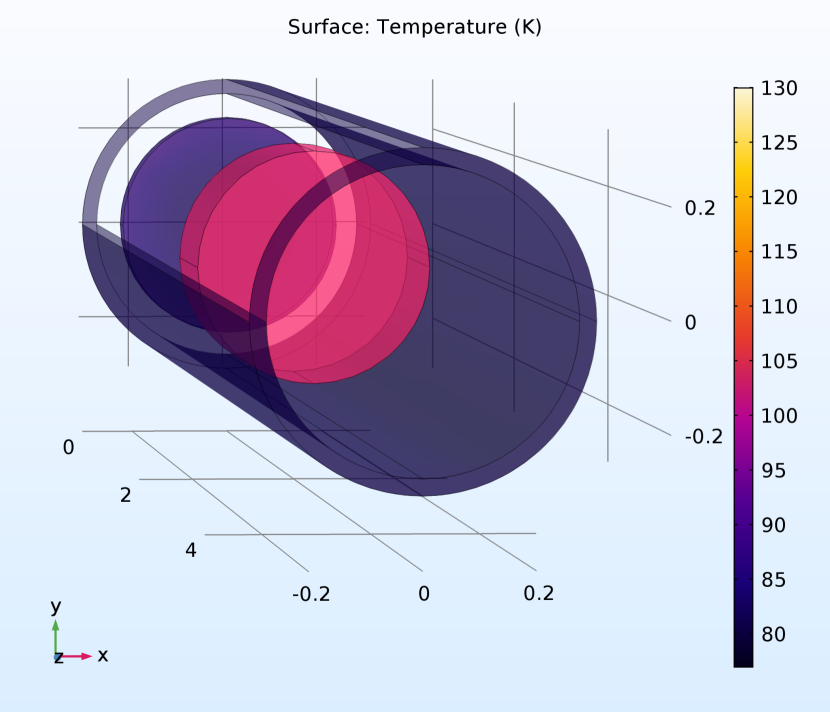

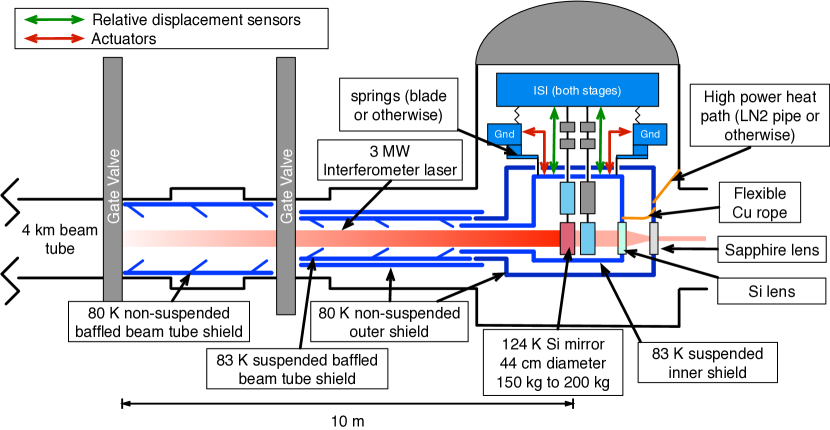

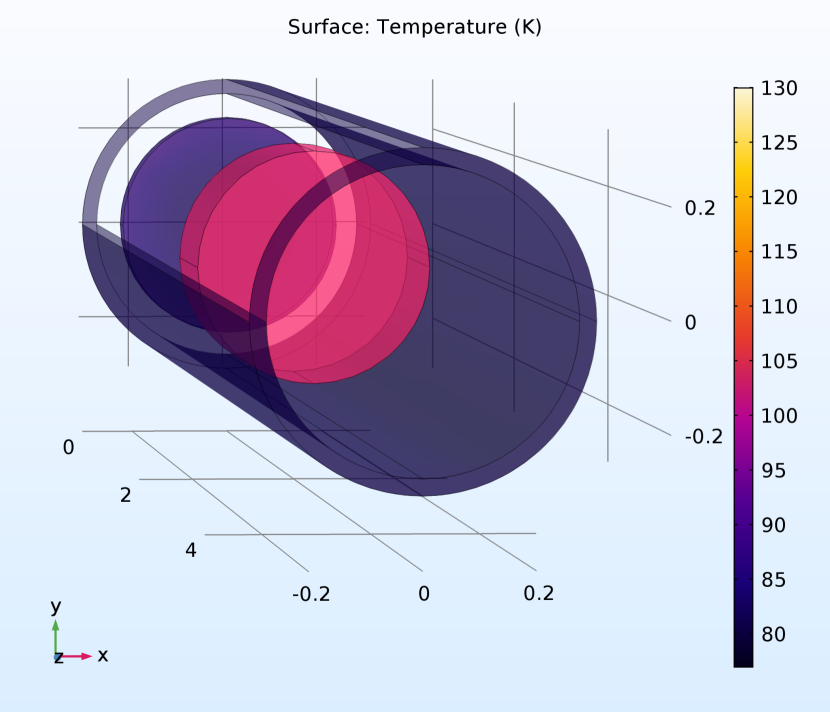

Radiative cooling and thermal management

The Voyager test masses must be cooled to 123 K while remaining freely suspended as pendulums for seismic isolation. This rules out conductive cooling through mechanical contacts, which would short-circuit the vibration isolation chain. Instead, Voyager uses radiative cooling: the test mass exchanges heat with a cold environment through thermal radiation.

The thermal design involves several coupled challenges:

Heat deposition: The circulating laser deposits power through absorption in the mirror coatings (~0.5 ppm per surface) and substrate (~0.1 ppm/cm). At 2 MW circulating power, even sub-ppm absorption deposits ~1 W in each test mass.

Emissivity coatings: The barrel and back faces of the test mass (the non-optical surfaces) need high emissivity to maximize radiative cooling power. Two candidate materials have been characterized:

- CNT (carbon nanotube) coatings: Prokhorov et al. (2020) measured the mechanical loss of carbon nanotube black coatings on silicon wafers and found lower loss than the alternative, making CNT the preferred candidate for Voyager’s emissivity coating.

- Acktar Black: Abernathy et al. (2016) characterized the mechanical loss of Acktar Black coatings on silicon. While effective as a high-emissivity coating, the mechanical loss was higher than CNT, adding more thermal noise.

Thermal time constants: A 200 kg silicon mass at 123 K, cooling radiatively through its non-optical surfaces, has thermal time constants of hours to days. Temperature stability must be maintained below ~1 mK to keep thermoelastic noise at the zero-crossing minimum. This requires careful control of the heat shield temperatures and precise monitoring of the test mass temperature (likely through the reflected laser beam properties).

Shapiro et al. (2017) demonstrated cryogenically cooled, ultra-low-vibration silicon mirrors at Stanford — achieving simultaneous cryogenic operation and high-quality vibration isolation in a prototype system. This work validated the basic concept of radiative cooling for precision interferometry at cryogenic temperatures.

Laser and photodetection at 2 µm

Silicon is transparent at wavelengths above ~1.1 µm, but the choice between 1550 nm and 2050 nm involves engineering trade-offs. The Voyager baseline selects 2050 nm because silicon’s optical absorption decreases at longer wavelengths, reducing the heat load on the test masses.

Laser sources at 2 µm are less mature than the Nd:YAG lasers at 1064 nm used in current LIGO. Candidate technologies include:

- Thulium-doped fiber lasers (~1940–2050 nm): the most developed option, with commercial systems reaching ~100 W. However, they have not yet demonstrated the combination of high power (>200 W), low intensity noise, and low frequency noise required for Voyager.

- Holmium-doped systems (~2050–2100 nm): an alternative fiber laser approach, less developed but targeting the exact Voyager wavelength.

- OPO-based sources: optical parametric oscillators can generate tunable output near 2 µm. They offer excellent noise properties but have power and reliability limitations.

No laser source at 2 µm currently meets all of Voyager’s requirements simultaneously. Laser development is one of the critical-path technology items for the project.

Photodetection is equally challenging. At 1064 nm, LIGO uses silicon photodiodes with quantum efficiency (QE) exceeding 99% and negligible dark current. At 2 µm, the available photodetector technology is extended InGaAs, which has significantly higher dark current, lower QE (~80%), and greater sensitivity to temperature fluctuations.

The quantum efficiency penalty directly impacts the detector’s quantum noise. With 80% QE, 20% of the signal photons are lost before measurement, degrading the signal-to-noise ratio and partially negating the benefit of squeezed light injection. This motivated the development of sum-frequency generation (SFG) — an alternative approach where 2 µm signal light is coherently upconverted to ~800 nm before detection on a high-QE silicon photodiode. See our SFG project page for details.

Coatings for Voyager

Voyager requires low-loss optical coatings that work at 1550–2050 nm on silicon substrates at 123 K. This is a distinct challenge from the room-temperature fused silica coatings in Advanced LIGO, and is covered in depth on our Coating Thermal Noise page. Here we summarize the key issues.

The mechanical loss of amorphous coatings depends on temperature through the two-level system (TLS) model: defect states in the amorphous network have a distribution of barrier heights, and different defect populations are thermally activated at different temperatures. The loss angle \(\phi(T)\) must be mapped from 300 K down to 123 K for every candidate coating material. Some materials (like titania-doped tantala) show a loss peak near 150 K that could be problematic for Voyager.

Candidate coating materials:

- Amorphous silicon / silica (aSi:SiO₂): The Voyager reference design baseline. Amorphous silicon has very low mechanical loss but high optical absorption, requiring careful optimization of layer thicknesses to minimize the field intensity in the high-loss material.

- AlGaAs crystalline coatings: Epitaxially grown GaAs/AlGaAs multilayers with extremely low mechanical loss (\(\phi \sim 10^{-5}\)). The main challenges are birefringence (which couples to laser noise) and scaling to the 45 cm Voyager test mass diameter.

- Titania-doped tantala (Ti:Ta₂O₅): The current Advanced LIGO high-index material. Loss at 123 K must be characterized to determine whether the cryogenic loss peak is acceptable.

The Caltech silicon double cavity apparatus (built by Yeaton-Massey and continued by Eichholz) is designed to measure coating thermal noise directly at Voyager-relevant conditions: silicon substrates at cryogenic temperatures with candidate coating stacks, using a rigid cavity readout.

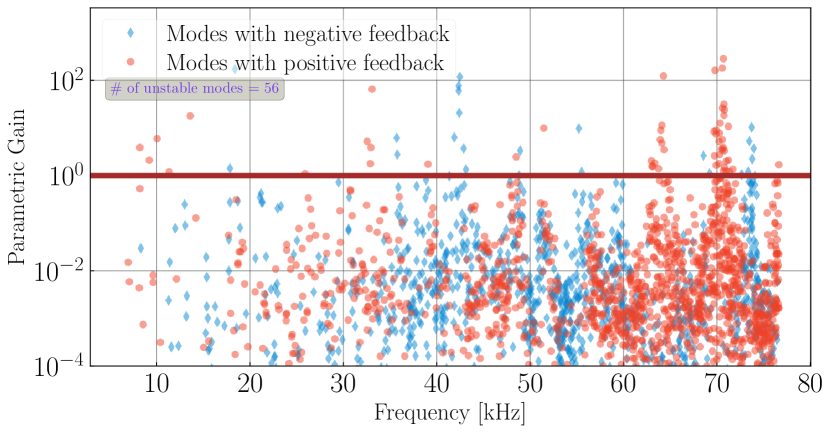

Parametric instabilities

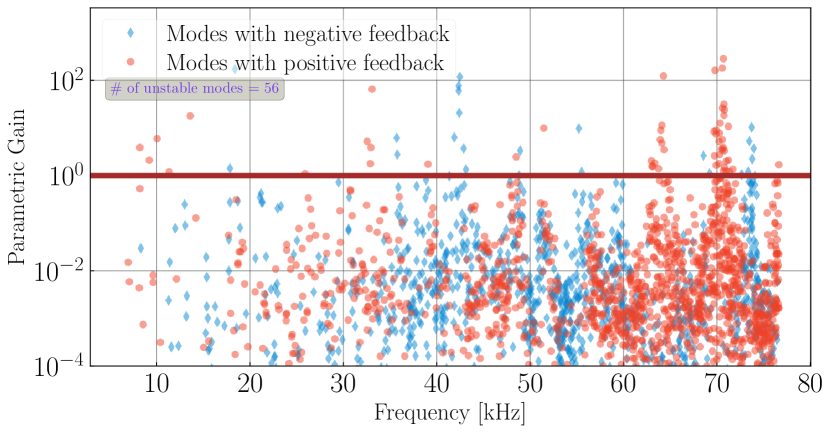

When high circulating laser power interacts with high-Q mechanical resonances of the test mass, radiation pressure can excite acoustic (elastic) modes through a process called parametric instability (PI). The circulating optical power modulates the cavity length, which modulates the intracavity power, which exerts radiation pressure that drives the mechanical mode — a positive feedback loop if the mechanical mode frequency falls near an optical cavity resonance.

Blair et al. (2017) demonstrated the first electrostatic damping of a parametric instability at Advanced LIGO — applying feedback forces through electrodes near the test mass surface to suppress an unstable 15 kHz mode. This validated the concept of active PI damping, which is essential for Voyager where the number of unstable modes is expected to be larger.

Voyager’s silicon test masses have different PI characteristics than fused silica:

- Higher acoustic mode frequencies due to silicon’s higher Young’s modulus and sound speed

- More unstable modes (~65 predicted below 60 kHz) due to the higher circulating power

- Different damping requirements: the electrostatic actuators used for PI damping must be designed to avoid introducing mechanical loss (per the Klochkov et al. 2022 constraints)

Active damping strategies include electrostatic feedback (demonstrated at LIGO) and thermal tuning of mode frequencies (shifting modes away from optical resonances by locally heating the test mass).

Related programs

Voyager is not an isolated project — several international programs share core technology challenges, and R&D progress in one program directly benefits the others.

Einstein Telescope (ET) is a proposed European third-generation detector: underground, triangular geometry, with a xylophone design that separates the low-frequency instrument (cryogenic silicon, 10–20 K) from the high-frequency instrument (room-temperature silica). The low-frequency ET instrument shares Voyager’s core technologies — silicon test masses, long-wavelength lasers, cryogenic operation — but operates at a much lower temperature and uses a different optical configuration. Technology developments for Voyager (coating characterization at cryogenic temperatures, laser development at 2 µm, radiative cooling physics) feed directly into ET design.

ET Pathfinder is a tabletop-scale prototype at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, specifically designed to test cryogenic silicon interferometry technologies at the component and subsystem level. It operates silicon test masses at cryogenic temperatures with laser light at 1550 nm and 2 µm — directly testing Voyager-relevant hardware. Results from ET Pathfinder provide early validation of assumptions in both the Voyager and ET designs.

Future longer-baseline detectors in the US and elsewhere are expected to use silicon test masses at 2 µm — leveraging Voyager technology (silicon optics, long-wavelength lasers, coatings) at larger scale. Voyager serves as the technology pathfinder: demonstrating silicon interferometry in a real detector environment before it is scaled to longer baselines.

KAGRA (Kamioka, Japan) is the world’s first cryogenic gravitational-wave detector, operating since 2020. However, KAGRA uses sapphire test masses at 1064 nm cooled to 20 K — a fundamentally different material choice from Voyager’s silicon. Sapphire brings its own challenges: birefringence, limited crystal size, and higher optical absorption than silicon at the relevant wavelengths. While KAGRA provides invaluable operational experience with cryogenic detector systems (vibration isolation, thermal control, vacuum compatibility), the specific material and wavelength technologies are largely distinct from Voyager.

Technology overlap matrix

| Technology | Voyager | ET (low-freq) | ET Pathfinder | Future US | KAGRA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon test masses | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ (sapphire) |

| Cryogenic operation | 123 K | 10–20 K | 10–123 K | Optional | 20 K |

| 2 µm laser | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ (1064 nm) |

| Radiative cooling | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | If cryo | Conductive |

| Coating R&D (cryo) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Different |

| Existing infrastructure | ✓ (4 km LIGO) | New (10 km) | New (tabletop) | New (longer) | Existing (3 km) |

Connections to other fields

The technologies developed for Voyager have applications well beyond gravitational-wave detection.

Precision timekeeping and optical clocks

Silicon cavities at cryogenic temperatures are used as ultra-stable optical references for the world's most precise atomic clocks. The same CTE zero-crossing at 123 K that Voyager exploits for low thermal noise is used in clock cavities to achieve fractional length stability below 10⁻¹⁷. Coating thermal noise is the dominant limit in both applications.Quantum optomechanics

High-Q silicon resonators at cryogenic temperatures are platforms for quantum optomechanics experiments — preparing macroscopic mechanical oscillators in quantum states, observing quantum back-action, and testing quantum mechanics at new mass scales. Voyager's 200 kg test masses would be the most massive objects ever operated near the quantum ground state of their center-of-mass motion.Cryogenic engineering

Radiative cooling of large masses to precisely controlled temperatures without mechanical contact is relevant to space-based instruments (where vibration isolation is natural but power is limited), cryogenic particle detectors, and quantum computing platforms that require vibration-free cryogenic environments.Semiconductor physics

Voyager pushes the frontiers of silicon material characterization: optical absorption at levels below 0.1 ppm/cm, mechanical loss at the 10⁻⁹ level, surface treatments that preserve bulk properties, and bonding techniques for attaching suspension fibers without degrading Q. These measurements advance the fundamental understanding of silicon as a precision material.Multi-messenger astronomy

The scientific payoff of Voyager — 125× the detection rate — would enable routine electromagnetic follow-up of gravitational-wave sources. With hundreds of binary neutron star mergers detected per year (compared to roughly one per month with current LIGO), multi-messenger campaigns could systematically map the equation of state of nuclear matter, measure the Hubble constant independently, and identify the sites of r-process nucleosynthesis across cosmic time.Our contributions

The EGG group led the Voyager conceptual design study and continues to drive key technology development areas.

-

Voyager reference design: R. X. Adhikari, Odylio Aguiar, K. Arai, Bryan Barr, and Riccardo Bassiri, et al., “A Cryogenic Silicon Interferometer for Gravitational-wave Detection,” Classical and Quantum Gravity (2020). DOI — The comprehensive design study defining Voyager’s optical configuration, noise budget, and technology requirements.

-

Astrophysical science case: R. X. Adhikari, P. Ajith, Y. Chen, J. A. Clark, V. Dergachev, N. V. Fotopoulos, S. E. Gossan, I. Mandel, M. Okounkova, V. Raymond, and J. S. Read, “Astrophysical science metrics for next-generation gravitational-wave detectors,” Classical and Quantum Gravity (2019). DOI — Quantitative science metrics showing how Voyager’s sensitivity improvement translates to astrophysical discovery potential.

-

Next-generation sensitivity studies: B. P. Abbott, R. Abbott, R. X. Adhikari, S. B. Anderson, and K. Arai, et al., “Exploring the sensitivity of next generation gravitational wave detectors,” Classical and Quantum Gravity (2017). DOI — Systematic exploration of sensitivity for next-generation detector configurations.

-

Silicon emissivity measurements: Marcio, Jr. Constancio, Rana X. Adhikari, Odylio D. Aguiar, Koji Arai, Aaron Markowitz, Marcos A. Okada, and Chris C. Wipf, “Silicon emissivity as a function of temperature,” International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer (2020). DOI — Measured total hemispherical emissivity of silicon from 100–300 K, providing essential data for radiative cooling design.

-

CNT emissivity coatings: L. G. Prokhorov, V. P. Mitrofanov, B. Kamai, A. Markowitz, Xiaoyue Ni, and R. X. Adhikari, “Measurement of mechanical losses in the carbon nanotube black coating of silicon wafers,” Classical and Quantum Gravity (2020). DOI — Characterized carbon nanotube black coatings on silicon for radiative cooling with lower mechanical loss than alternatives.

-

Acktar Black characterization: M. R. Abernathy, N. Smith, W. Z. Korth, R. X. Adhikari, L. G Prokhorov, D. V. Koptsov, and V. P. Mitrofanov, “Measurement of mechanical loss in the Acktar Black coating of silicon wafers,” Classical and Quantum Gravity (2016). DOI — Mechanical loss measurements of Acktar Black coatings on silicon, establishing baseline for emissivity coating comparison.

-

Electric field loss in silicon: Y. Yu. Klochkov, L. G. Prokhorov, M. S. Matiushechkina, R. X. Adhikari, and V. P. Mitrofanov, “Using silicon disk resonators to measure mechanical losses caused by an electric field,” Review of Scientific Instruments (2022). DOI — Measured electric-field-induced mechanical loss in silicon resonators, constraining electrostatic actuator design for Voyager.

-

Cryogenic vibration isolation: Brett Shapiro, Rana X. Adhikari, Odylio Aguiar, Edgard Bonilla, Danyang Fan, Litawn Gan, Ian Gomez, Sanditi Khandelwal, Brian Lantz, Tim MacDonald, and Dakota Madden-Fong, “Cryogenically cooled ultra low vibration silicon mirrors for gravitational wave observatories,” Cryogenics (2017). DOI — Demonstrated simultaneous cryogenic cooling and ultra-low vibration isolation for silicon mirrors.

-

Parametric instability damping: Carl Blair, Richard Abbott, B. P. Abbott, R. X. Adhikari, and S. B. Anderson, et al., “First Demonstration of Electrostatic Damping of Parametric Instability at Advanced LIGO,” Physical Review Letters (2017). DOI — Demonstrated electrostatic damping of a parametric instability at Advanced LIGO.

-

Newtonian noise subtraction: Jennifer C. Driggers, Jan Harms, and Rana X. Adhikari, “Subtraction of Newtonian noise using optimized sensor arrays,” Physical Review D (2012). DOI — Optimized sensor array methods for subtracting Newtonian noise, applicable to Voyager’s low-frequency sensitivity.

Key references

Design and science case

- Adhikari, Arai, Brooks, Wipf et al., “A Cryogenic Silicon Interferometer for Gravitational-wave Detection,” CQG 37, 165003 (2020) — the Voyager reference design

- Adhikari et al., “Astrophysical science metrics for next-generation gravitational-wave detectors,” CQG 36, 245010 (2019) — quantitative science reach

- Abbott, Adhikari et al., “Exploring the sensitivity of next generation gravitational wave detectors,” CQG 34, 044001 (2017) — systematic sensitivity study

Silicon properties and thermal management

- Constancio et al., “Silicon emissivity as a function of temperature,” IJHMT 157, 119863 (2020) — emissivity from 100–300 K

- Klochkov et al., “Using silicon disk resonators to measure mechanical losses caused by an electric field,” RSI 93, 044501 (2022) — electric field loss constraints

- Shapiro et al., “Cryogenically cooled ultra low vibration silicon mirrors,” Cryogenics 81, 83 (2017) — cryo + vibration isolation demonstration

Emissivity coatings

- Prokhorov et al., “Measurement of mechanical losses in the carbon nanotube black coating,” CQG 37, 025010 (2020) — CNT characterization

- Abernathy et al., “Measurement of mechanical loss in the Acktar Black coating,” CQG 33, 185002 (2016) — Acktar Black baseline

Parametric instabilities and noise subtraction

- Blair et al., “First Demonstration of Electrostatic Damping of Parametric Instability at Advanced LIGO,” PRL 118, 151102 (2017)

- Driggers, Harms, Adhikari, “Subtraction of Newtonian noise using optimized sensor arrays,” PRD 86, 102001 (2012)

Related programs

- Punturo et al., “The Einstein Telescope: a third-generation gravitational wave observatory,” CQG 27, 194002 (2010) — ET design study

- Aso et al., “Interferometer design of the KAGRA gravitational wave detector,” PRD 88, 043007 (2013) — KAGRA design

Related publications

-

A Cryogenic Silicon Interferometer for Gravitational-wave Detection

-

Silicon emissivity as a function of temperature

-

Using silicon disk resonators to measure mechanical losses caused by an electric field

-

Measurement of mechanical losses in the carbon nanotube black coating of silicon wafers

-

Measurement of mechanical loss in the Acktar Black coating of silicon wafers

-

Cryogenically cooled ultra low vibration silicon mirrors for gravitational wave observatories

-

Astrophysical science metrics for next-generation gravitational-wave detectors

-

Exploring the sensitivity of next generation gravitational wave detectors

-

First Demonstration of Electrostatic Damping of Parametric Instability at Advanced LIGO

-

Subtraction of Newtonian noise using optimized sensor arrays