Generative Optical Design

Gradient-based optimization over universal interferometer models to autonomously discover detector topologies that outperform human designs.

Research area

Gravitational-wave detector design has relied on human intuition for six decades: physicists propose interferometer topologies, analyze their noise spectra, and incrementally refine them. But the space of possible optical configurations is astronomically vast — far larger than any human could explore in a lifetime. We built Urania, a gradient-based algorithm that searches this space autonomously, and it discovered detector designs that dramatically outperform anything humans have conceived.

Contents:

- Why optimize detector topology?

- The universal interferometer model

- The Urania algorithm

- What Urania discovered

- The GW Detector Zoo

- Robustness and experimental realism

- Competing approaches

- Connections to other fields

- Our contributions

- Current status and open questions

- Key references

Why optimize detector topology?

The history of gravitational-wave interferometry is a sequence of topology changes, each yielding orders-of-magnitude improvement:

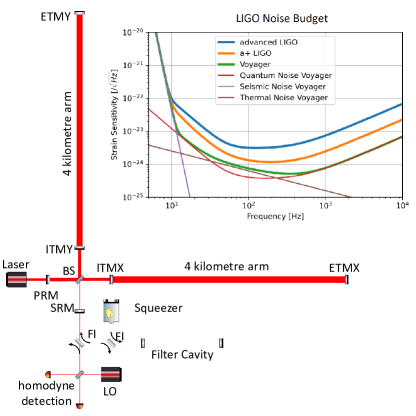

- Michelson interferometer (1887): equal-arm light interference for displacement sensing

- Fabry-Pérot arms (1980s–90s): resonant cavities amplify the signal by recycling photons ~300 times in each arm, boosting effective arm length from 4 km to ~1200 km

- Power recycling (2000s): a mirror at the input sends rejected light back into the interferometer, increasing circulating power without a more powerful laser

- Signal recycling (2010s): a mirror at the output reshapes the frequency response — trading bandwidth for peak sensitivity

- Frequency-dependent squeezing (2023): a 300-meter filter cavity rotates squeezed vacuum to reduce quantum noise at all frequencies simultaneously

Each step was a human insight. But the improvements have become harder to find: after dual-recycled Fabry-Pérot Michelson with frequency-dependent squeezing, what comes next? Next-generation detectors will need fundamentally new ideas to reach their science targets.

The key realization: the topology IS the physics. Different interferometer topologies exploit different quantum noise cancellation mechanisms. The standard quantum limit (SQL) sets a floor on the noise spectral density for a simple Michelson interferometer:

\[S_h^{\text{SQL}}(f) \propto \frac{\hbar}{m \omega^2 L^2}\]where $m$ is the mirror mass, $\omega = 2\pi f$, and $L$ is the arm length. But this limit can be evaded by topologies that create correlations between shot noise and radiation pressure noise — a fact known since Caves (1981) but difficult to exploit in practice because the space of possible correlating topologies is so large.

A brief history of interferometer topologies

| Year | Topology innovation | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1887 | Michelson equal-arm interferometer | Established optical interferometry |

| 1972 | Weiss: laser interferometer concept for GW detection | Founded the field |

| 1983 | Drever, Fabry-Pérot arm cavities | Signal amplification by resonance (~300×) |

| 1988 | Schilling: power recycling demonstrated | Recycled rejected light, boosted power |

| 1991 | Meers: dual recycling concept | Reshapeable frequency response |

| 2002 | Kimble et al.: QND interferometers | Squeezed-state injection to beat SQL |

| 2015 | LIGO first detection (dual-recycled FP Michelson) | Validation of the mature topology |

| 2019 | Tse et al.: squeezed light in LIGO | 3 dB broadband quantum noise reduction |

| 2023 | Jia et al.: frequency-dependent squeezing in LIGO | Broadband sub-SQL sensitivity |

| 2025 | Krenn, Drori & Adhikari: Urania | First autonomous topology discovery |

Every row before 2025 was a human-designed topology change. Urania automates this process.

The universal interferometer model

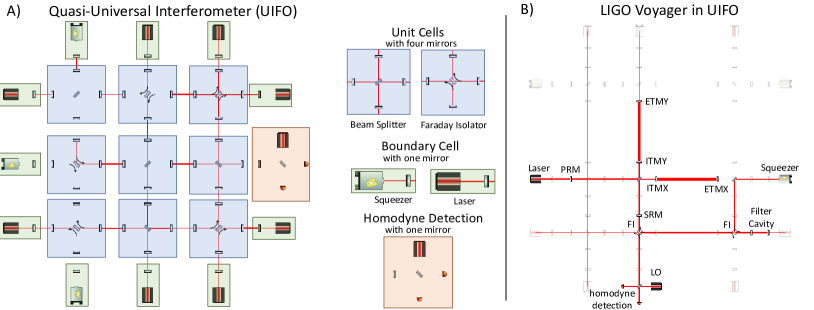

The central idea behind Urania is to encode all possible interferometer topologies within a single parameterized model. This model is the Quasi-Universal Interferometer (UIFO).

Structure

The UIFO is an $n \times n$ grid of unit cells, each containing a beam splitter, up to four mirrors (forming cavity-like structures), and potentially a Faraday isolator for non-reciprocal light routing. Light enters the grid from three of four boundaries (laser, squeezer, local oscillator) and exits at the fourth boundary to homodyne detection ports.

The critical insight: every known interferometer topology — Michelson, Sagnac, zero-area Sagnac, speed meters, Mach-Zehnder configurations — is a specific instance of the UIFO, obtained by setting particular beam splitter reflectivities and mirror positions. The UIFO is strictly more general than any topology proposed to date.

Transfer matrix formalism

Each unit cell is described by a scattering matrix that relates incoming and outgoing fields. For a beam splitter with amplitude reflectivity $r$ and transmissivity $t = \sqrt{1 - r^2}$:

\[S_{\text{BS}} = \begin{pmatrix} r & it \\ it & r \end{pmatrix}\]Mirrors add round-trip phases $\phi = 2kL$ depending on mirror positions $L$. The full interferometer transfer function — mapping input fields (laser, squeezer, vacuum) to output fields (detection ports) — is obtained by composing all unit cell scattering matrices across the grid. This composition is fully differentiable, which is what makes gradient-based optimization possible.

Connection to photonic circuit theory

The UIFO draws directly on the Reck et al. (1994) and Clements et al. (2016) decompositions of universal unitary transformations. These results, originally developed for quantum photonics, prove that any unitary transformation on $N$ optical modes can be implemented by a triangular (Reck) or rectangular (Clements) array of beam splitters and phase shifters.

The UIFO extends these constructions in two ways:

-

Resonant elements. Photonic circuit decompositions use only beam splitters and phase shifters. The UIFO adds mirrors that form Fabry-Pérot cavities within the mesh, enabling resonant amplification — essential for interferometric sensing where cavity buildup is the primary sensitivity mechanism.

-

Non-reciprocal routing. Faraday isolators allow light to travel in only one direction through a cell, enabling topologies like signal recycling where reflected and transmitted fields must be separated.

The result: the UIFO inherits the universality guarantee from photonic circuit theory while extending it to the resonant, non-reciprocal regime required for gravitational-wave detection. This is why it can represent every known detector topology — and many unknown ones.

The Urania algorithm

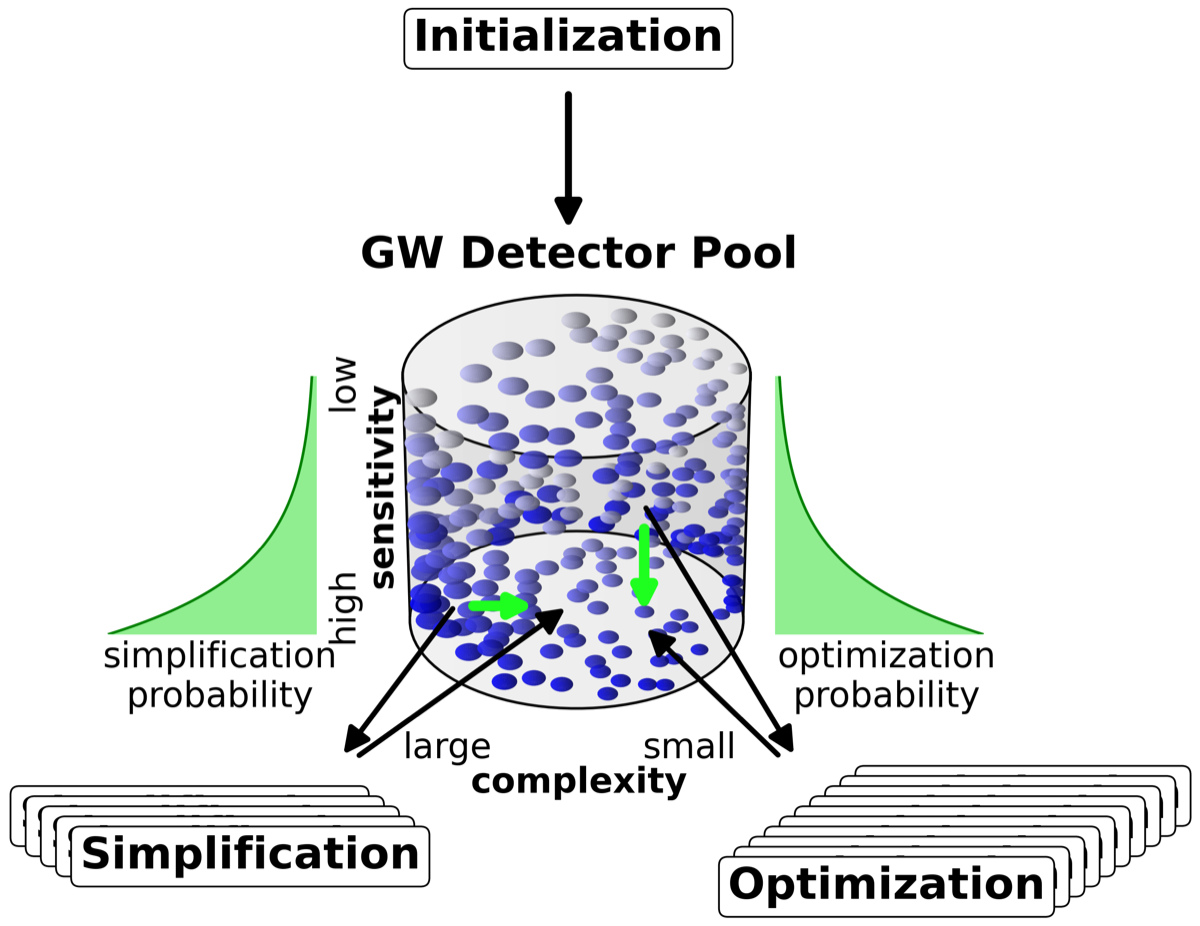

Named after the Greek Muse of astronomy, Urania discovers detector topologies through two complementary operations applied iteratively:

Optimization

Starting from a random initialization of all UIFO parameters, gradient descent maximizes a physics-driven cost function. Because the entire transfer function — from input fields through the UIFO to output noise spectral density — is differentiable, Urania computes exact gradients with respect to every beam splitter reflectivity, mirror position, and cavity length simultaneously.

Simplification

After optimization converges, Urania identifies and removes unnecessary optical elements (beam splitters near $r = 0$ or $r = 1$, mirrors with negligible effect). This produces minimal designs that are easier to interpret physically and more practical to build.

Pool-based search

Urania maintains a diverse population of candidate solutions spanning different complexity levels (UIFO grid sizes). New candidates are drawn from the pool using Boltzmann selection — higher-performing solutions are more likely to be selected, but lower-performing ones still have a chance, preventing premature convergence to local optima.

The cost function

Urania maximizes the observable volume of the Universe for a given astrophysical source class. For compact binary coalescences, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is:

\[\rho^2 = 4 \int_0^\infty \frac{|h(f)|^2}{S_h(f)}\, df\]where $h(f)$ is the source waveform and $S_h(f)$ is the detector strain noise spectral density. The observable volume scales as the cube of the luminosity distance at which the detector achieves a threshold SNR:

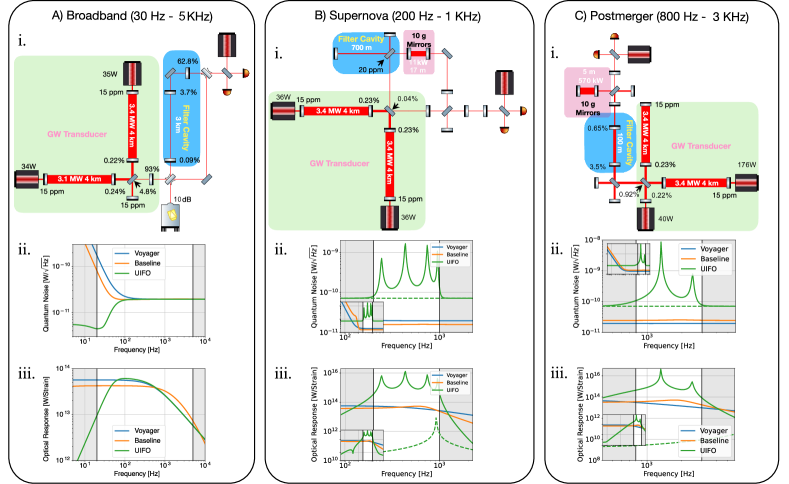

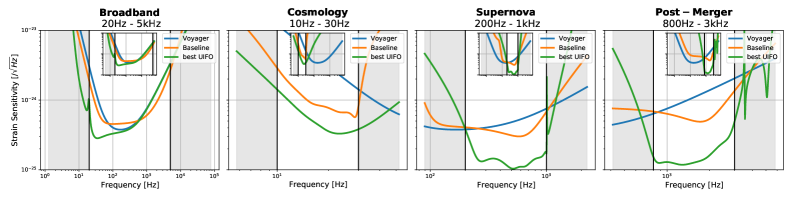

\[V \propto d_L^3 \propto \rho^3\]Different astrophysical targets weight different frequency bands:

- Binary black holes (BBH): Broadband, 20 Hz–5 kHz

- Cosmology (early inspiral): Low frequency, 10–30 Hz

- Supernovae: 200 Hz–1 kHz

- Post-merger neutron star oscillations: 800 Hz–3 kHz

Urania runs separate optimization campaigns for each target, producing topologies specialized for different science goals.

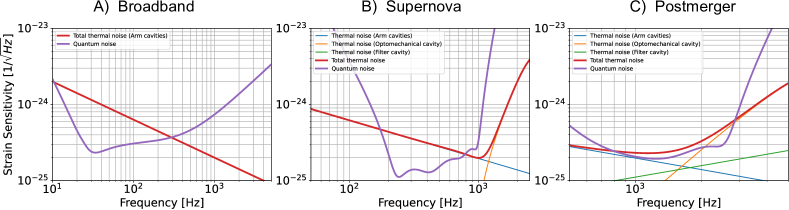

The noise model: what's included

Urania’s cost function includes three noise sources:

-

Quantum noise — Shot noise (photon counting statistics) and radiation pressure noise (photon momentum kicks on mirrors). These are computed exactly from the UIFO transfer function and depend on the topology. This is the noise source that topology optimization primarily targets.

-

Coating Brownian thermal noise — Thermomechanical fluctuations in the mirror coatings, modeled using the fluctuation-dissipation theorem. The thermal noise depends on beam spot sizes, coating mechanical loss angles, and mirror geometry — all of which can vary between discovered topologies (since different topologies may use different numbers of mirrors with different beam sizes).

-

Optical losses — Absorption and scattering in mirrors and beam splitters, modeled as fractional power loss per surface. Losses degrade squeezing and inject vacuum noise.

Not yet included: Suspension thermal noise, seismic noise, Newtonian gravity noise, technical laser noise (frequency and intensity), alignment control noise, parametric instabilities. Adding these may shift the optimal topologies and is an active area of investigation.

What Urania discovered

Applied to LIGO Voyager as the baseline, Urania autonomously discovered over 50 novel interferometer topologies. The results are striking:

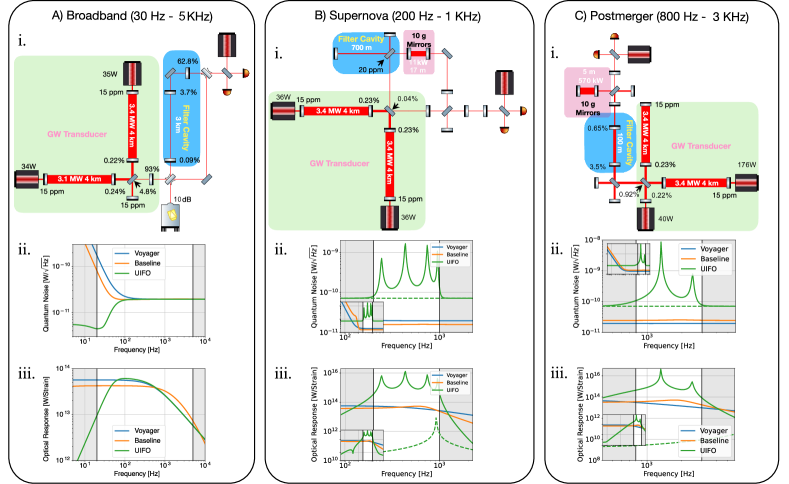

Broadband solution

A novel topology that outperforms parameter-optimized LIGO Voyager across the full detection band (20 Hz–5 kHz). The improvement comes from an internal signal recycling configuration that no expert had proposed — the topology creates effective negative dispersion that partially cancels the positive dispersion from the arm cavities, broadening the detector bandwidth without sacrificing peak sensitivity.

Post-merger solution

The most dramatic result: a radical topology optimized for the 800 Hz–3 kHz band achieves a ~50× improvement in observable volume compared to Voyager. This would enable detection of post-merger neutron star oscillations — a key probe of the nuclear equation of state — that would otherwise require a next-generation detector with much longer arms.

Supernova solution

Optimized for 200 Hz–1 kHz, the supernova topology uses a qualitatively different quantum noise cancellation strategy than the broadband solution, exploiting interference between multiple internal cavities to suppress radiation pressure noise in the target band.

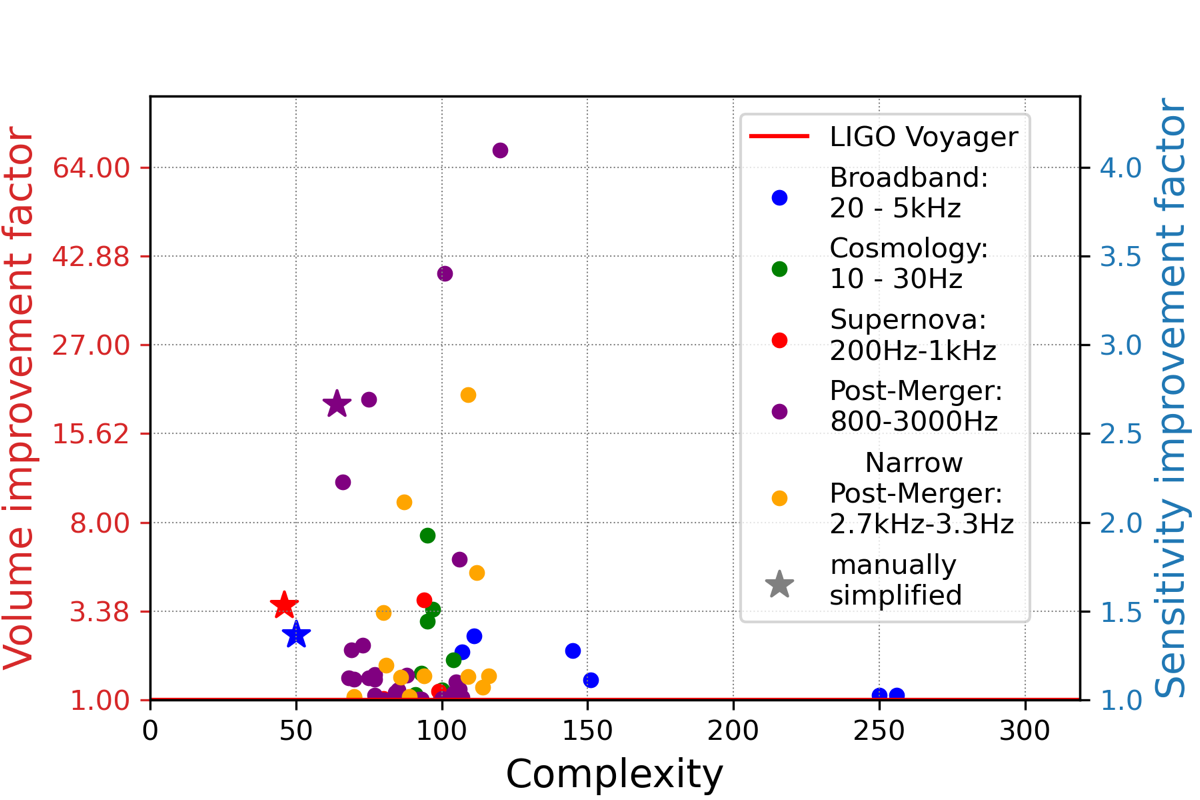

The improvement metric is the ratio of observable volumes:

\[\eta = \frac{V_{\text{UIFO}}}{V_{\text{Voyager}}} = \left(\frac{d_{\text{UIFO}}}{d_{\text{Voyager}}}\right)^3\]For the post-merger target, $\eta \approx 50$; for broadband BBH, $\eta \approx 2$–$5$ depending on the solution.

Critically, analysis of the best solutions revealed entirely new physics ideas at their core — not just parameter tweaks to known designs. The solutions contain internal cavity structures with specific detunings that create quantum noise correlations no expert had previously considered. In this sense, Urania’s discoveries are “superhuman”: they exploit physics that was always available but that human designers had not found.

The GW Detector Zoo

Urania produced more than 50 distinct solutions with improved sensitivity over the Voyager baseline. These solutions — collectively named the GW Detector Zoo — span a range of complexities (measured by number of free optical parameters) and sensitivities.

Key observations:

- Diversity is a feature. Different solutions trade off complexity versus performance versus robustness. Some solutions are minimal — fewer optical components than LIGO — yet outperform it.

- No single best design. The optimal topology depends on the science target. A detector optimized for post-merger signals is suboptimal for cosmological measurements, and vice versa.

- Simplification preserves performance. The grey stars in the scatter plot show manually simplified designs that retain most of the improvement at much lower complexity.

- All designs publicly available. The full Zoo — parameters, noise curves, and optical layouts — is open-source at the GW Detector Zoo.

Robustness and experimental realism

A design that works on paper but is too fragile to build is useless. Urania’s noise model includes realistic experimental constraints:

Thermal noise

The discovered topologies use different numbers and configurations of mirrors than LIGO Voyager. Do they have worse coating thermal noise? The analysis shows that the simplified solutions have comparable or lower total thermal noise than Voyager across all three target bands.

Parameter sensitivity

Perturbation analysis reveals which parameters need tight fabrication tolerances. Some beam splitter reflectivities must be held to ~0.1% precision; others are insensitive to 10% changes. This analysis identifies the critical components that would need the most engineering attention in a real detector.

Recalibration

Many parameter perturbations can be compensated by re-optimizing a subset of parameters — analogous to how LIGO operators tune the detector after installation. The gap between “paper design” and “buildable instrument” is narrower than it first appears, because the designs are robust to perturbations that can be corrected in situ.

What the noise model includes and what it doesn't

Included in Urania’s cost function:

- Shot noise and quantum radiation pressure noise (exact, from transfer matrix)

- Coating Brownian thermal noise (fluctuation-dissipation theorem)

- Optical losses: absorption (~1 ppm/surface) and scattering (~10 ppm/surface)

Not yet included:

- Suspension thermal noise (pendulum thermal motion)

- Seismic noise (ground vibration coupling)

- Newtonian gravity noise (fluctuating mass density near test masses)

- Technical laser noise (frequency and intensity fluctuations)

- Alignment control noise (angular degrees of freedom)

- Parametric instabilities (opto-mechanical mode coupling)

Adding these noise sources may shift the optimal topologies — a design that evades quantum noise might be limited by suspension thermal noise at low frequencies. Incorporating the full noise budget is a key next step.

Competing approaches

Bayesian parameter optimization

Richardson et al. (Phys. Rev. D, 2022) used Bayesian optimization to tune LIGO A+ optical parameters (squeezing angle, filter cavity length, signal recycling detuning) for maximum sensitivity. This approach is effective for parameter optimization within a fixed topology but does not search over topologies — the interferometer layout is predetermined. Urania subsumes this: it can optimize both topology and parameters simultaneously.

Reinforcement learning for control

Deep Loop Shaping (Buchli et al., Science, 2025) applies reinforcement learning to optimize LIGO’s feedback control policies — a complementary problem. RL is well-suited for control because the control loop includes non-differentiable elements. But for topology optimization, where the physics is fully differentiable, gradient methods are more sample-efficient.

Evolutionary and genetic algorithms

Genetic algorithms have been applied to antenna design, metamaterial optimization, and some optical problems. They maintain diverse populations and can escape local optima, but are less sample-efficient than gradient methods for smooth cost functions because they do not use gradient information. For the UIFO’s ~100–1000 continuous parameters, gradient descent converges orders of magnitude faster.

Topology optimization in structural mechanics

Standard topology optimization (Bendsøe & Sigmund) discretizes a design domain into voxels and optimizes material distribution to minimize compliance or maximize stiffness. While conceptually similar, it targets structural problems where the physics is described by partial differential equations over a spatial domain — quite different from the optical transfer function approach used by Urania.

Inverse design in nanophotonics

Adjoint-method optimization of nanophotonic devices (Molesky et al. 2018, Piggott et al. 2015) shares Urania’s philosophy of gradient-based design. These methods optimize the geometry of a single optical component (waveguide, coupler, filter). Urania operates at a higher level of abstraction: it optimizes the topology of an entire multi-component instrument.

Connections to other fields

AI for science

Urania is part of a broader movement to use AI and machine learning for experimental design — reviewed by Krenn et al. (Nature Reviews Physics, 2023). Previous work in this area includes MELVIN/THESEUS for quantum optics experiments and AlphaFold for protein structure prediction. Urania extends this paradigm to macroscopic precision instruments.

Quantum photonics

The UIFO’s grid structure descends directly from universal photonic circuits (Reck et al. 1994, Clements et al. 2016). These same architectures are used in photonic quantum computing and programmable photonic processors. Advances in one field feed the other: improvements in photonic circuit design could inspire new UIFO architectures, and Urania’s optimization techniques could be applied to photonic circuit design.

Generative molecular design

Urania’s approach is analogous to generative molecular design (Sanchez-Lengeling & Aspuru-Guzik, 2018): both search vast combinatorial spaces for structures that optimize a physical objective function. The key shared insight is that encoding discrete structures (molecule topologies, interferometer topologies) as continuous parameters enables gradient-based search.

Other precision instruments

The Urania framework is not specific to gravitational waves. Any precision optical instrument where the topology is a design variable could benefit: atomic clocks, dark matter detectors, quantum sensors, laser gyroscopes. The UIFO model would need adaptation (different noise sources, different cost functions), but the optimization machinery transfers directly.

Our contributions

-

Digital Discovery of Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detectors (Krenn, Drori & Adhikari, Phys. Rev. X, 2025) — The Urania algorithm, UIFO model, and discovery of 50+ novel detector topologies. First demonstration of autonomous detector topology optimization. Showed that AI can discover genuinely new physics ideas, not just optimize within known paradigms.

-

Optimizing gravitational-wave detector design for squeezed light (Richardson, Pandey, Bytyqi, Edo & Adhikari, Phys. Rev. D, 2022) — Bayesian optimization of LIGO A+ optical parameters for squeezed-light injection. Precursor methodology that optimized within a fixed topology, motivating the topology search that became Urania.

-

Scattering loss in precision metrology due to mirror roughness (Drori, Eichholz, Edo, Yamamoto, Enomoto, Venugopalan, Arai & Adhikari, JOSA A, 2022) — Optical loss modeling from real mirror surface profiles. Understanding scattering losses is essential for realistic detector optimization — these loss models feed directly into Urania’s noise budget.

-

Astrophysical science metrics for next-generation gravitational-wave detectors (Adhikari et al., CQG, 2019) — Defined the astrophysical figures of merit — observable volume for BBH, BNS, supernovae, stochastic background — that Urania uses as its cost function. Established the science case for 3G detectors.

-

GW Detector Zoo — Open-source repository of all 50+ discovered detector topologies with full parameters, noise curves, and optical layouts.

Current status and open questions

-

Experimental validation. No discovered topology has been built. The most immediate question: which design has the best ratio of predicted improvement to experimental complexity? A tabletop-scale prototype in the 40m lab at Caltech could test the key physics of a discovered topology.

-

Extended noise models. Incorporating suspension thermal noise, seismic noise, and Newtonian noise into the cost function. These noise sources dominate below ~30 Hz and may favor different topologies than the current quantum-noise-dominated optimization.

-

Multi-objective optimization. Simultaneously optimizing for multiple astrophysical targets (BBH + BNS + post-merger) with Pareto-optimal solutions that represent the best available tradeoffs.

-

Manufacturing constraints. Incorporating fabrication tolerances directly into the cost function, so Urania preferentially discovers designs that are robust to real-world imprecisions rather than being told “make it better” and then checking robustness afterward.

-

Beyond gravitational-wave detectors. Applying the Urania framework to other precision optical instruments: atom interferometers, optical clocks, quantum key distribution systems, laser rangefinders.

-

Connection to Deep Loop Shaping. The RL-based control optimization and Urania’s topology optimization are complementary. A combined approach — optimizing both the detector topology and its feedback control system — could yield further improvements.

Key references

The Urania paper and precursors

-

Krenn, Drori & Adhikari, “Digital Discovery of Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detectors,” Phys. Rev. X 15, 021012 (2025). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevX.15.021012 — The primary paper: Urania algorithm, UIFO model, 50+ discovered topologies, 50× post-merger volume improvement.

-

Richardson, Pandey, Bytyqi, Edo & Adhikari, “Optimizing gravitational-wave detector design for squeezed light,” Phys. Rev. D 105, 102002 (2022). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.105.102002 — Bayesian optimization of LIGO A+ parameters. Precursor that motivated the topology search.

-

Drori, Eichholz, Edo, Yamamoto, Enomoto, Venugopalan, Arai & Adhikari, “Scattering loss in precision metrology due to mirror roughness,” JOSA A (2022). DOI:10.1364/JOSAA.455127 — Optical loss modeling from real surface profiles. Fed into Urania’s noise budget.

Interferometer physics foundations

-

Caves, “Quantum-mechanical noise in an interferometer,” Phys. Rev. D 23, 1693 (1981). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.23.1693 — Established quantum noise limits and the role of squeezed states.

-

Kimble, Levin, Matsko, Thorne & Vyatchanin, “Conversion of conventional gravitational-wave interferometers into quantum-nondemolition interferometers by modifying their input and/or output optics,” Phys. Rev. D 65, 022002 (2001). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.022002 — How to beat the SQL with input squeezing and variational readout.

-

Buonanno & Chen, “Signal recycled laser-interferometer gravitational-wave detectors as optical springs,” Phys. Rev. D 65, 042001 (2001). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.042001 — Optical spring effect in signal recycled interferometers.

-

Braginsky, Gorodetsky & Khalili, “Optical bars in gravitational wave detectors,” Phys. Lett. A 232, 340 (1997). DOI:10.1016/S0375-9601(97)00413-1 — Noise not associated with local Lorentz forces; speed meter concepts.

-

Miao, Adhikari, Ma, Zhao & Chen, “Towards the Fundamental Quantum Limit of Linear Measurements of Classical Signals,” PRL 119, 050801 (2017). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.050801 — Fundamental quantum limits for linear measurements.

Universal optical circuits

-

Reck, Zeilinger, Bernstein & Bertani, “Experimental realization of any discrete unitary operator,” PRL 73, 58 (1994). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.58 — Universal unitary decomposition into beam splitter arrays.

-

Clements, Humphreys, Metcalf, Kolthammer & Walmsley, “Optimal design for universal multiport interferometers,” Optica 3, 1460 (2016). DOI:10.1364/OPTICA.3.001460 — Improved rectangular decomposition with better loss scaling.

-

Shen et al., “Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits,” Nature Photon. 11, 441 (2017). DOI:10.1038/nphoton.2017.93 — Optical neural networks using the same beam splitter mesh architecture.

Detector design and science targets

-

Adhikari et al., “Astrophysical science metrics for next-generation gravitational-wave detectors,” CQG 36, 245010 (2019). DOI:10.1088/1361-6382/ab3cff — Science metrics (observable volume, localization, early warning) that define Urania’s cost function.

-

Somiya, “Detector configuration of KAGRA,” CQG 29, 124007 (2012). DOI:10.1088/0264-9381/29/12/124007 — KAGRA design: the first cryogenic, underground detector.

-

Punturo et al., “The Einstein Telescope: a third-generation gravitational wave observatory,” CQG 27, 194002 (2010). DOI:10.1088/0264-9381/27/19/194002 — Einstein Telescope design study.

AI for science and optimization

-

Krenn, Pollice, Guo, Aldeghi, Cervera-Lierta, Friederich, Gomes, Häse, Jinich, Nigam, Yao & Aspuru-Guzik, “On scientific understanding with artificial intelligence,” Nature Rev. Phys. 4, 761 (2022). DOI:10.1038/s42254-022-00518-3 — Review of AI for scientific discovery and experiment design.

-

Krenn, Kottmann, Tischler & Aspuru-Guzik, “Conceptual understanding through efficient automated design of quantum optical experiments,” Phys. Rev. X 11, 031044 (2021). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevX.11.031044 — THESEUS: automated quantum optics experiment design.

-

Sanchez-Lengeling & Aspuru-Guzik, “Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models, differentiable engineering, and molecular autoencoders,” Science 361, 360 (2018). DOI:10.1126/science.aat2663 — Inverse molecular design framework.

-

Flam-Shepherd, Zhu & Aspuru-Guzik, “Language models can learn complex molecular distributions,” Nature Commun. 13, 3293 (2022). DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-30839-x — Generative language models for molecular design.

Further reading

Phase transitions in optimization

One of Urania’s most intriguing findings is that the optimization loss curves exhibit phase transitions — discontinuous jumps where the algorithm discovers qualitatively new strategies. These are not numerical artifacts; they correspond to moments when the optimizer finds a new topology that exploits a different physical mechanism (e.g., transitioning from a Michelson-like topology to one with internal signal recycling).

Phase transitions in optimization landscapes are well-studied in physics (spin glasses, statistical mechanics) and machine learning (neural network training). Their appearance in detector optimization suggests that the UIFO landscape has a rich structure with distinct basins corresponding to topologically different designs. Understanding this landscape — and potentially navigating it more efficiently — is an open research direction.