Computational Experiment Design

Using optimization and computational search to design experiments that maximize sensitivity to quantum-gravity signatures, systematically exploring interferometer topologies and measurement protocols.

Gallery

Research area

How do you design an experiment to detect a signal you have never seen, from a theory that might be wrong, using technology that does not yet exist? In gravitational-wave physics and quantum gravity research, the design space of possible experiments is so vast that human intuition can explore only a thin slice. Computational experiment design treats the entire process — choosing a topology, selecting readout schemes, setting operating parameters, balancing noise budgets — as a formal optimization problem with rigorous information-theoretic objectives.

Contents:

- The framework: from intuition to optimization

- Fisher information and the Cramer-Rao bound

- Multi-objective optimization and Pareto fronts

- Application: detector parameter optimization

- Application: coating design

- Application: quantum gravity experiments

- Competing approaches

- Our contributions

- Current status and open questions

- Key references

The framework: from intuition to optimization

Traditional experimental design in physics is iterative and intuition-driven: a theorist predicts a signal, an experimentalist builds an apparatus to look for it, and the design is refined through experience. This works well when the design space is small and the physics is well understood. It fails when:

-

The design space is combinatorially large. An interferometer experiment has continuous parameters (laser power, mirror masses, cavity lengths) and discrete choices (topology, readout scheme, quantum state). The joint space grows exponentially.

-

The physics target is uncertain. Quantum gravity experiments aim to detect signals whose existence is theoretical. Different models predict different signatures — holographic noise, gravitational decoherence, modified commutation relations — each requiring different optimal configurations.

-

Multiple objectives compete. A design that maximizes sensitivity to one signal may be suboptimal for another. Real experiments also face cost, complexity, and feasibility constraints that trade off against sensitivity.

Computational experiment design addresses all three by casting the problem as: maximize an information-theoretic objective function over the space of experimental configurations, subject to feasibility constraints. The objective function encodes what you want to learn; the optimization algorithm searches for the best way to learn it.

This page describes the framework — the mathematical and computational machinery for optimal experiment design. For a specific application of these ideas to gravitational-wave detector topology discovery, see the Generative Optical Design project, where the Urania algorithm applied gradient-based optimization within a universal interferometer model to discover more than 50 novel detector topologies.

Fisher information and the Cramer-Rao bound

The central mathematical tool is the Fisher information matrix (FIM). For a measurement with outcome $x$ that depends on parameters $\boldsymbol{\theta}$, the Fisher information is:

\[\mathcal{F}_{ij}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = -\mathbb{E}\!\left[\frac{\partial^2 \ln p(x|\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \theta_i\, \partial \theta_j}\right]\]| where $p(x | \boldsymbol{\theta})$ is the likelihood function. The Cramer-Rao bound then guarantees that the covariance of any unbiased estimator satisfies: |

This is a matrix inequality: the estimation uncertainty for any parameter $\theta_i$ is bounded below by $[\mathcal{F}^{-1}]_{ii}$. The Fisher information tells you the best possible measurement precision before you collect any data — it depends only on the experimental design and the noise model.

Why Fisher information, not signal-to-noise ratio?

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is the most common figure of merit in experimental physics. For a single parameter (e.g., strain amplitude), maximizing SNR and maximizing Fisher information are equivalent. But Fisher information is strictly more general:

-

Multi-parameter estimation. When multiple parameters must be estimated simultaneously (e.g., signal amplitude, frequency, sky location, polarization), the FIM captures correlations between parameters. A design that is optimal for one parameter may be poor for another due to parameter degeneracies. The FIM reveals these trade-offs.

-

Model selection. The FIM framework extends naturally to Bayesian model comparison, where the goal is not to estimate a parameter but to distinguish between competing theories — exactly the situation in quantum gravity experiments.

-

Design-dependent noise. In interferometers, the noise spectral density $S_h(f)$ depends on the experimental configuration. The FIM accounts for this: changing the topology changes both the signal response and the noise, and the FIM captures the net effect on measurement precision.

For gravitational-wave detectors, the Fisher information for strain amplitude $h_0$ reduces to the familiar matched-filter SNR:

\[\mathcal{F}(h_0) = 4\int_0^\infty \frac{|h(f)|^2}{S_h(f)}\, df = \rho^2\]But for multi-parameter problems — inferring masses, spins, sky location, equation of state — the full FIM is essential. The Cramer-Rao bound has been used extensively in gravitational-wave parameter estimation (e.g., Cutler & Flanagan 1994; Vallisneri 2008) and in calibration error analysis (Hall, Cahillane, Izumi, Smith & Adhikari 2019).

| Experiment design as FIM optimization. The experimental configuration — topology, readout, operating parameters — enters through the likelihood $p(x | \boldsymbol{\theta})$. Different configurations yield different Fisher information matrices. The design problem becomes: choose the configuration that maximizes the Fisher information for the parameters of interest. For a single parameter, this means maximizing a scalar. For multiple parameters, one must choose a scalar summary of the FIM — common choices include the determinant (D-optimality, maximizing the volume of the confidence ellipsoid) or the trace (A-optimality, minimizing average variance). |

Multi-objective optimization and Pareto fronts

Real experiments never optimize a single objective. Sensitivity must be balanced against cost, complexity, technical risk, and the breadth of science accessible. Multi-objective optimization formalizes this trade-off.

Given $k$ objective functions $f_1(\mathbf{x}), \ldots, f_k(\mathbf{x})$ over a design space $\mathbf{x}$, a configuration $\mathbf{x}^*$ is Pareto-optimal if no other configuration improves one objective without worsening another. The set of all Pareto-optimal configurations forms the Pareto front — a surface in objective space that represents the best achievable trade-offs.

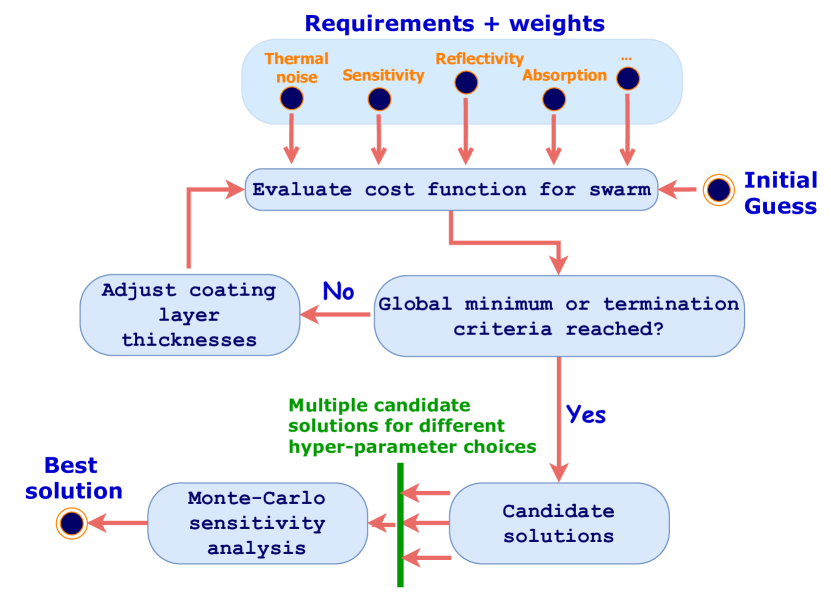

For gravitational-wave detector design, the relevant objectives include:

- Observable volume for different astrophysical source classes (binary black holes, neutron star mergers, supernovae, post-merger oscillations)

- Optical complexity (number of components, alignment degrees of freedom)

- Robustness to fabrication tolerances and environmental perturbations

- Cost and schedule risk

No single design dominates on all axes. The Pareto front gives decision-makers a menu of rationally defensible choices — each representing a different bet on which science is most valuable. This is a sharper basis for design decisions than optimizing a single number.

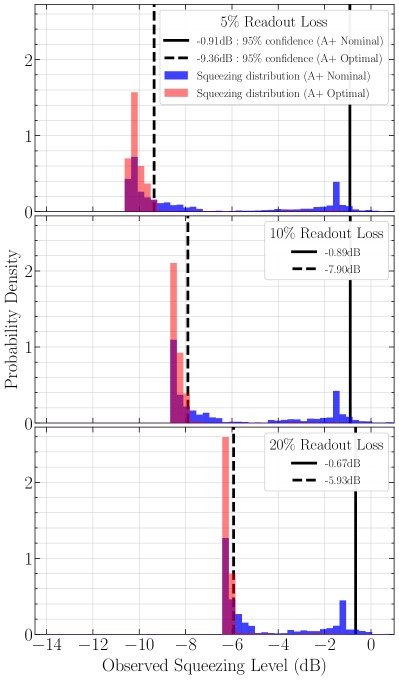

Application: detector parameter optimization

The most direct application of computational experiment design in the EGG group is optimizing gravitational-wave detector parameters for maximum sensitivity to squeezed light.

Richardson, Pandey, Bytyqi, Edo & Adhikari (2022) performed a Bayesian optimization of the LIGO A+ design, optimizing the signal recycling cavity geometry to maximize observed squeezing in the presence of realistic optical losses — scattering from point absorbers, mode mismatch, and fabrication tolerances. The key insight: the nominal A+ design is fragile. Small perturbations to mirror curvatures or positions degrade squeezing dramatically. The optimized design achieves comparable peak performance but is far more robust.

This work optimizes parameters within a fixed topology — the interferometer layout is given, and the algorithm tunes continuous variables (cavity lengths, mirror curvatures, beam sizes). The Generative Optical Design project extends this to topology optimization, where the layout itself is a learnable variable. Together, these approaches cover the full hierarchy: parameter optimization within a topology, topology optimization within a model class, and (eventually) model-class optimization across fundamentally different experimental approaches.

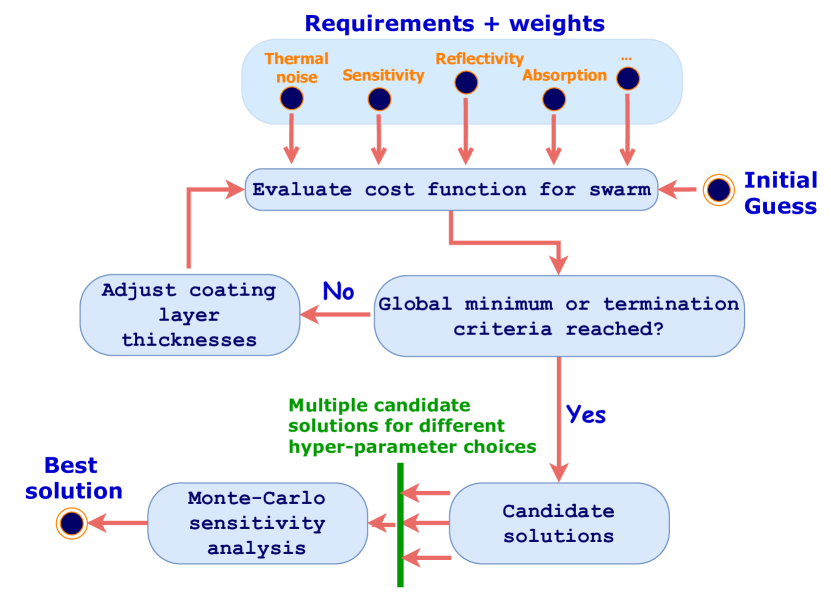

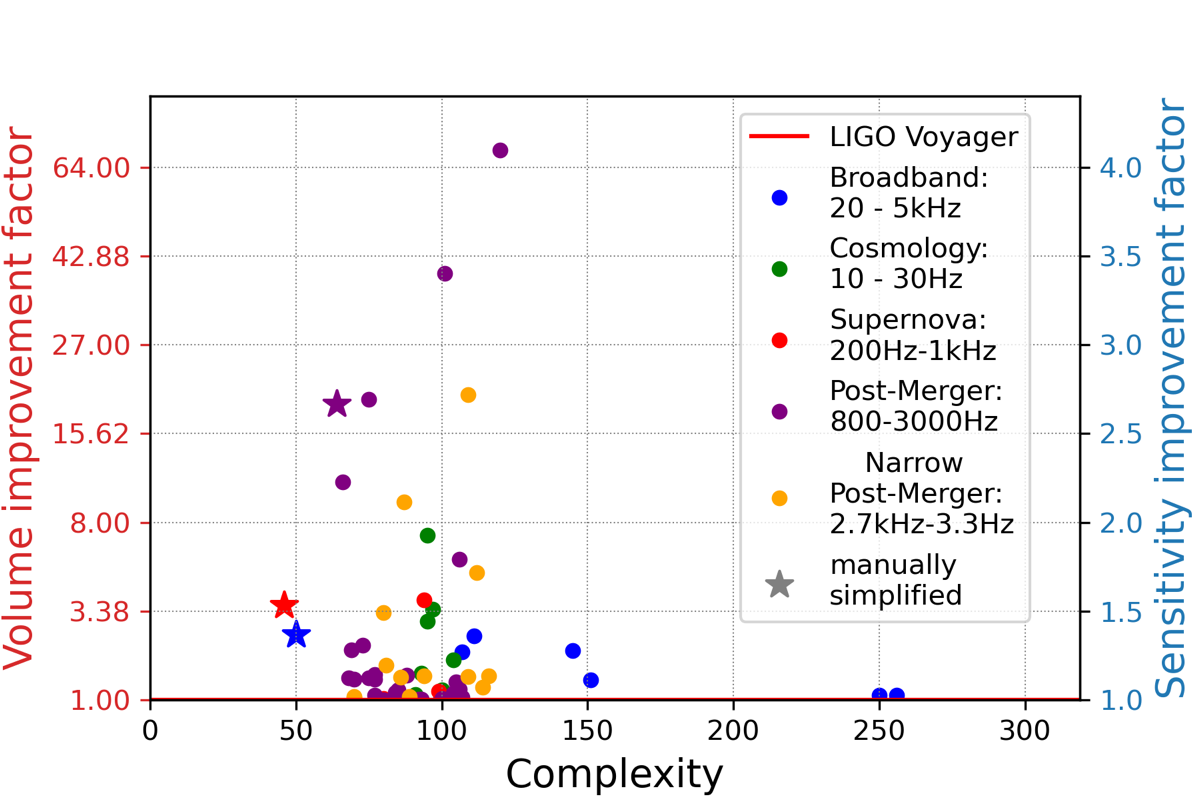

Application: coating design

Mirror coatings are a critical noise source in gravitational-wave detectors — coating thermal noise limits sensitivity in the most important frequency band (50-200 Hz). But coatings must simultaneously satisfy multiple requirements: target reflectivity at specific wavelengths, low absorption, low mechanical loss, and tolerance to fabrication errors. This is a multi-objective optimization problem.

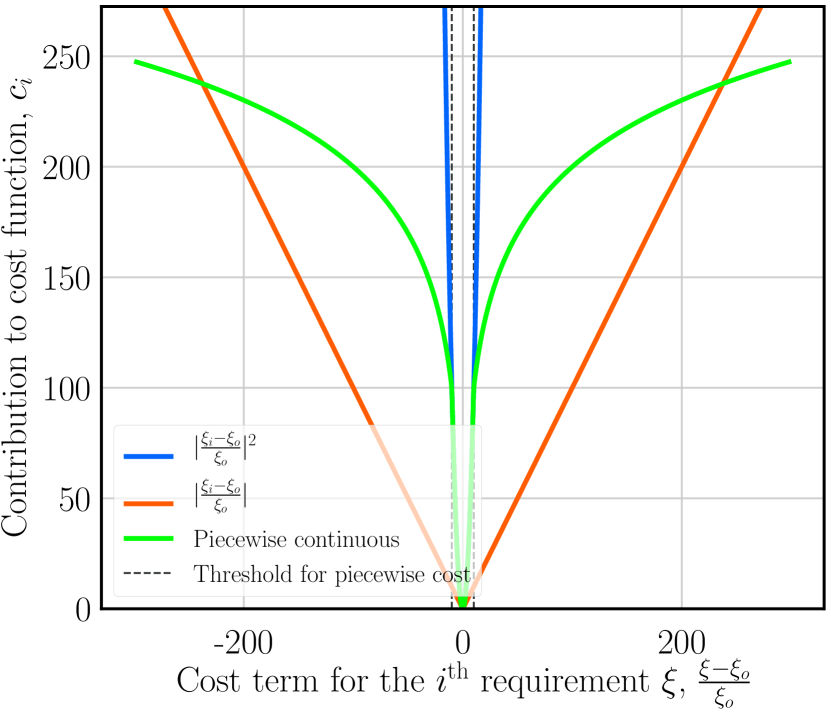

Venugopalan, Salces-Cárcoba, Arai & Adhikari (2024) developed a global optimization framework for multilayer dielectric coatings. The approach defines a composite cost function that penalizes deviations from target reflectivity, excess thermal noise, absorption, and sensitivity to layer-thickness errors, then uses a global optimizer (differential evolution) to search the high-dimensional space of layer thicknesses.

Why coatings are hard to optimize

A typical high-reflectivity mirror coating has 20-40 alternating layers of two materials (e.g., SiO$_2$/Ta$_2$O$_5$), each with a thickness that can be independently varied. This gives a 20-40 dimensional continuous design space with a rugged landscape — many local minima, sharp constraints (reflectivity must exceed 99.999%), and competing objectives (lower thermal noise requires thinner high-loss layers, but thinner layers reduce reflectivity).

Traditional coating design uses quarter-wave stacks — all layers have optical thickness $\lambda/4$ — which is analytically tractable but far from optimal. The quarter-wave constraint reduces the design space from $\sim 30$ free parameters to zero (given the number of layers), throwing away most of the optimization potential.

Global optimization explores the full space. The Venugopalan et al. approach found coating designs that achieve the same reflectivity as quarter-wave stacks with 25-40% lower thermal noise by redistributing layer thicknesses so that more of the optical field energy resides in the low-loss material. The optimizer also discovered designs with superior robustness to fabrication errors — critical because real coating deposition has ~1% layer-thickness uncertainty.

The same framework applies to the multi-wavelength coatings needed for SFG-based readout (simultaneous operation at 1064 nm, 2050 nm, and 700 nm) and to crystalline coatings for LIGO Voyager.

Application: quantum gravity experiments

The most speculative — and potentially most consequential — application is designing experiments to test quantum gravity. Here the framework addresses a fundamental challenge: how do you optimize an experiment for a signal that might not exist, predicted by a theory that might be wrong?

Different quantum-gravity models predict qualitatively different experimental signatures:

| Model class | Signal type | Key design parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Holographic noise | Correlated displacement fluctuations | Beam overlap geometry, cross-correlation bandwidth |

| Gravitational decoherence | Loss of quantum coherence in massive systems | Test mass, coherence time, isolation |

| Modified dispersion relations | Frequency-dependent speed of light | Baseline length, photon energy range |

| Spacetime foam | Accumulated phase noise | Path length, wavelength, integration time |

Each row implies a different optimal experiment. Fisher information quantifies this: the FIM for holographic noise detection depends on cross-spectral density between interferometer beams; for decoherence, it depends on the visibility decay rate of a matter-wave interferometer. The optimal designs are qualitatively different because the signals couple to different experimental degrees of freedom.

This creates a meta-design problem: which model should you optimize for? Three strategies:

-

Model-specific optimization. Pick a single theory and design the most sensitive experiment for it. Maximizes sensitivity but risks building an experiment that is blind to the actual signal (if the chosen model is wrong).

-

Minimax optimization. Design an experiment that maximizes the worst-case sensitivity across a set of models. Robust but conservative — the resulting design may be mediocre for every model.

-

Portfolio optimization. Allocate resources across multiple experiments, each optimized for a different model class. This is the multi-objective approach applied at the program level, with the Pareto front representing trade-offs between sensitivity to different theories.

The tabletop tests of quantum gravity program at Caltech employs a version of strategy (3): multiple experimental approaches (GQuEST for holographic noise, optomechanical systems for decoherence, atom interferometry for equivalence principle tests) cover different regions of theory space.

Competing approaches

Manual expert design

The traditional approach: experienced physicists design experiments based on physical intuition, simplified noise models, and incremental refinement. This remains the dominant paradigm and has produced every existing gravitational-wave detector. Its limitation is scalability — human designers explore a tiny fraction of the design space, and intuition about one noise source may not transfer to a different regime.

Grid search and Monte Carlo sampling

The simplest computational approach: evaluate the objective function on a grid or at random points in the design space. Scales poorly with dimensionality (curse of dimensionality) but requires no gradient information. Used for low-dimensional problems or as a sanity check.

Bayesian optimization

Models the objective function as a Gaussian process and uses an acquisition function (e.g., expected improvement) to select the next evaluation point. Sample-efficient for expensive objective functions (each evaluation requires a full noise simulation). Richardson et al. (2022) applied this to LIGO A+ parameter optimization.

Gradient-based optimization

When the objective function is differentiable — as in the Urania framework — gradient descent is orders of magnitude more efficient than gradient-free methods. The key enabler is a differentiable physics model (transfer matrix formalism for interferometers, or analytic noise models for coatings). Scales to thousands of parameters.

Evolutionary and genetic algorithms

Maintain a population of candidate designs, evolve them through selection, crossover, and mutation. Can escape local optima and handle mixed discrete-continuous design spaces. Less sample-efficient than gradient methods but more flexible. Differential evolution was used by Venugopalan et al. (2024) for coating optimization.

Reinforcement learning

Learns a design policy by interacting with a simulation environment. Most natural when the design process has sequential decisions (e.g., adding components one at a time) or when the objective is non-differentiable. Deep Loop Shaping applied RL to feedback controller design — a related but distinct problem.

Our contributions

-

Optimizing gravitational-wave detector design for squeezed light (Richardson, Pandey, Bytyqi, Edo & Adhikari, Phys. Rev. D, 2022) — Bayesian optimization of LIGO A+ optical parameters for maximum squeezing robustness. Demonstrated that computational optimization finds designs far more tolerant of real-world imperfections than nominal human designs.

-

Global optimization of multilayer dielectric coatings for precision measurements (Venugopalan, Salces-Cárcoba, Arai & Adhikari, Opt. Express, 2024) — Global optimization framework for mirror coatings balancing reflectivity, thermal noise, and fabrication tolerance. Found designs with 25-40% lower thermal noise than standard quarter-wave stacks.

-

Digital Discovery of Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detectors (Krenn, Drori & Adhikari, Phys. Rev. X, 2025) — The Urania algorithm: gradient-based topology optimization within a universal interferometer model. Discovered more than 50 novel detector topologies, including designs with ~50x improved observable volume. Described in detail on the Generative Optical Design page.

-

Systematic calibration error requirements for gravitational-wave detectors via the Cramer-Rao bound (Hall, Cahillane, Izumi, Smith & Adhikari, CQG, 2019) — Applied the Cramer-Rao bound to derive calibration accuracy requirements for LIGO, showing how systematic errors in the calibration pipeline propagate to astrophysical parameter biases.

-

Astrophysical science metrics for next-generation gravitational-wave detectors (Adhikari et al., CQG, 2019) — Defined the figures of merit — observable volume, sky localization, early warning time — that serve as objective functions for computational detector design.

-

Towards the Fundamental Quantum Limit of Linear Measurements of Classical Signals (Miao, Adhikari, Ma, Pang & Chen, PRL, 2017) — Established the quantum Cramer-Rao bound for linear measurements of classical signals, providing the fundamental information-theoretic limit that any detector design must respect.

Current status and open questions

-

Unified framework. The three strands — parameter optimization (Richardson et al.), coating optimization (Venugopalan et al.), and topology optimization (Krenn, Drori & Adhikari) — are currently separate codebases with separate objective functions. A unified computational experiment design framework that jointly optimizes topology, parameters, and coatings is a natural next step.

-

End-to-end differentiability. Urania’s topology optimization is differentiable, but the full noise budget (including suspension thermal noise, seismic noise, Newtonian noise) is not yet included. Making the complete noise model differentiable would enable end-to-end gradient-based optimization from topology to predicted science output.

-

Quantum gravity objective functions. The existing work uses astrophysical figures of merit (observable volume for compact binaries). Extending this to quantum gravity signatures requires defining appropriate Fisher information metrics for holographic noise, gravitational decoherence, and other predicted signals — and encoding them as differentiable cost functions.

-

Experimental validation. No computationally optimized topology has been built. The most immediate test would be a tabletop prototype of a Urania-discovered design in the 40m lab at Caltech. For coatings, optimized designs from Venugopalan et al. can be fabricated and measured against their predicted performance.

-

Design under deep uncertainty. All current methods assume the noise model is correct. In practice, real experiments encounter unexpected noise sources. Robust optimization that accounts for model uncertainty — not just parameter uncertainty — is an open problem.

Key references

EGG contributions

-

Richardson, Pandey, Bytyqi, Edo & Adhikari, “Optimizing gravitational-wave detector design for squeezed light,” Phys. Rev. D 105, 102002 (2022). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.105.102002 — Bayesian optimization of LIGO A+ parameters.

-

Venugopalan, Salces-Cárcoba, Arai & Adhikari, “Global optimization of multilayer dielectric coatings for precision measurements,” Opt. Express (2024). DOI:10.1364/OE.513807 — Multi-objective coating optimization.

-

Krenn, Drori & Adhikari, “Digital Discovery of Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detectors,” Phys. Rev. X 15, 021012 (2025). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevX.15.021012 — Topology optimization with Urania.

-

Hall, Cahillane, Izumi, Smith & Adhikari, “Systematic calibration error requirements for gravitational-wave detectors via the Cramer-Rao bound,” CQG 36, 205008 (2019). DOI:10.1088/1361-6382/ab368c — Fisher information applied to calibration.

-

Adhikari et al., “Astrophysical science metrics for next-generation gravitational-wave detectors,” CQG 36, 245010 (2019). DOI:10.1088/1361-6382/ab3cff — Science-driven objective functions.

-

Miao, Adhikari, Ma, Pang & Chen, “Towards the Fundamental Quantum Limit of Linear Measurements of Classical Signals,” PRL 119, 050801 (2017). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.050801 — Quantum Cramer-Rao bound.

Foundations of optimal experiment design

-

Fisher, “The Logic of Inductive Inference,” J. R. Stat. Soc. 98, 39 (1935). — Origin of the Fisher information concept.

-

Lindley, “On a Measure of the Information Provided by an Experiment,” Ann. Math. Stat. 27, 986 (1956). DOI:10.1214/aoms/1177728069 — Bayesian experimental design framework.

-

Chaloner & Verdinelli, “Bayesian Experimental Design: A Review,” Stat. Sci. 10, 273 (1995). DOI:10.1214/ss/1177009939 — Comprehensive review of Bayesian optimal experiment design.

-

Vallisneri, “Use and abuse of the Fisher information matrix in the assessment of gravitational-wave parameter-estimation prospects,” Phys. Rev. D 77, 042001 (2008). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.77.042001 — Practical guidance on FIM for GW parameter estimation.

Gravitational-wave parameter estimation

-

Cutler & Flanagan, “Gravitational waves from merging compact binaries: How accurately can one extract the binary’s parameters from the inspiral waveform?” Phys. Rev. D 49, 2658 (1994). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.49.2658 — Foundational FIM analysis for compact binary parameter estimation.

-

Finn, “Detection, measurement, and gravitational radiation,” Phys. Rev. D 46, 5236 (1992). DOI:10.1103/PhysRevD.46.5236 — Statistical framework for GW detection and measurement.